The Greatest Artist of Silent Cinema

A Love Letter to F.W Murnau

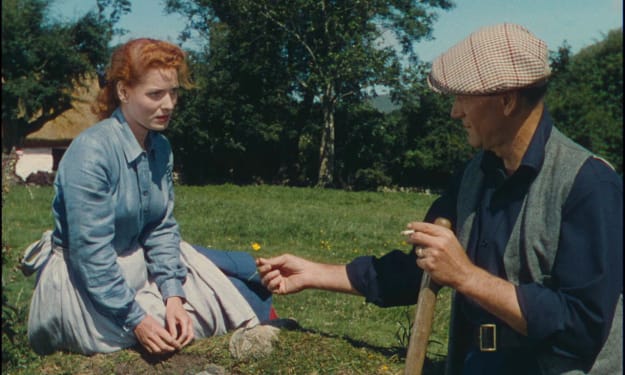

It is fitting, it is rather obvious, that the opening shot of the earliest surviving F.W Murnau film is of a young woman framed against a window pane, absorbed by the beauty of the world that surrounds her. Her silhouette casting a looming shadow over the pristinely designed interior of a Weimar Republic-era mansion. The shot in question comes from the underseen masterpiece Journey Into The Night (Murnau, 1921), which is not, of course, the first film F.W Murnau made, but is the earliest that has not been lost to time. Indeed, Murnau is a ghost director. Of the twenty-one films he made during his life, only twelve can be watched today. By all accounts, these nine lost films point to a cinematic legacy that is completely unmatched in its grandeur, unapologetic beauty, and historical importance. This grand legacy is, for now, incomplete, and these nine lost treasures have inevitably been imbued with a sense of mystery. Murnau should be named among the greatest artists of the cinema, but this earned legacy is marred by these mysteries, as well as the horrid restorations done to his survivors, an unjust, but not unearned, reputation as a horror icon as a direct result of his most famous work, and tales involving wealthy actresses throwing valuable film canisters into the Florida sea, and grave robbers mistaking a romantic-drama director as an occultist and stealing his skull. These are stories that deftly showcase the danger that comes when the general populace does not treat film as a serious art form - and so forth to the unfortunate restorations. Journey Into The Night has been lovingly restored by the Filmmuseum München in Germany, however this restoration has only been done to the original copy with German inter-titles, not the English version. The English copy is so beat up it should be considered borderline lost, meaning no inter-titles for the non-German speaker. What this does though, is highlight Murnau as a visual director. There has never been a better expressionist in film history. His films feel remarkably modern. Journey Into The Night functions more as an opera than a narrative film. The plot is beautifully tragic and feels ripped right out of the tradition of the theater. Even with unreadable title cards, the story and emotion come through clear as a bell. As a director, Murnau can be defined by his overwhelming (and frankly emotionally transcendent) visual expressionism, overtly theatrical plots, and unyielding sympathy for his characters. The introductory image from Journey Into The Night, a girl looking longingly out a window, appears again and again throughout the first half of his career. By Faust (Murnau, 1926), it becomes the plot of the films. This is not a motif, it is an obsession. Of course, what is meant with this is not the rather juvenile idea of a virginal woman that is oh-so Godly as she sings to the flowers and birds, but actually the purest form of love, innocence, and family simply encompassed by this image. This is idealism, if viewed through the ignorance of modern Americana and the contortion of these ideas by the Trump/Vance ticket, but for a country reeling in debt after the first world war, for a gay director forced to reside in loneliness for the entirety of his life, this image is the most beautiful thing in the world. Murnau's best use of this image comes in his second surviving film, The Haunted Castle (Murnau, 1921), in a particularly tender flashback sequence. It is this image alone that stays with the viewer after the film is over, and single handedly turns what could have been a childish murder mystery into, maybe not an essential film, but a no less rapturous work of early cinema. Murnau would continue to build on these themes throughout the early part of his career, eventually the window shot would be ditched in favor of all-encompassing plots that treated love as something divine. That idea of divinity culminates in Murnau's 1926 masterwork, the previously mentioned Faust, and a following trio of love stories that should be the films for which Murnau is best remembered, for they remain unrivaled in their sweetness, unpredictability, and visual audacity. These being, of course, the appropriately lauded Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (Murnau, 1927), the splendid American idyll City Girl (Murnau, 1930), and the docufiction Tabu: A Story of The South Seas (Murnau, 1931). Working backwards with these we have Tabu, A film which falls slightly behind the other two entries in our unofficial trilogy due to its unfortunate shades of ethnographic tourism. Those shades are there, despite its undeniably righteous intentions and soul-rattling emotional impact. One would be pretty callous not to mention the final call of Reri (a colossal performance by Anne Chevalier) to her beloved - “Across the great waters - I will come to you in your dreams - When the moon spreads its path on the sea - Farewell.” Coincidentally, heartbreakingly actually, these are the final words that close Murnau's career as he would die in a car crash one week before Tabu’s premiere. It’s an appropriate eulogy for a man whose films are the purest cinematic dreams. Indeed, punctuated by Murnau’s death, Tabu represents the death rattle of the silent film and is one of its last great offerings. In 1928 Murnau wrote the think piece “Films of the Future” - one of the greatest pieces of writing ever about the medium. Its opening makes the heart patter “What is the future of motion pictures? Alas, I am not an oracle. If I could answer you I would be, perhaps, the most important man in the world. For the screen has as great potential power as any other existing medium of expression. Already it is changing the habits of mankind - making people who live in different countries and speak different languages neighbors. In the future it may educate our children's children even better than books. It may put an end to war, for men do not fight when they understand each others’ hearts. I am of the opinion that as a world force, the screen has possibilities beyond imagining.” This quote is the essence of Tabu. Murnau made a film with the grandest intentions, that told of the purest love. He made it with a cast made up entirely of native islanders and non-english speakers. The film seems to want to demystify stereotypes about islanders and introduce a white audience into the beauty of pacific cultures. The crux of the story relies on a racist trope, but Murnau's compassion for human beings and hope for the possibility of foreign cinema, shines through the fully-realized main characters, the towering performances by the actors, and the sounding call of love reverberating across the sea. Tabu is the response to the call of City Girl. The former takes place in Bora-Bora, the latter in America's heartland. It is one of the greatest melodramas ever made, which puts it in top contention as one of the greatest films ever made, and has one of the greatest tracking shots ever put to screen. The camera glides through endless fields of wheat, dancing with lovers as they hold each other, framed against the Minnesota sky. The imagery is deeply American in its location, but universal in its tranquility. It should beat in the heart and mind of every human being. The girl at the window has been taken outside. She is free. At the turn of the emotional climax of the film, one is forced to ask how such beauty can even exist. City Girl is essential. Murnau's most beautiful love story comes in his most acclaimed film, Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans, and it really is a song.. One of the human species’ most beautiful songs. Here is a film that should not work. On paper it doesn’t. The subject matter is dark and ghastly and the imagery is borderline psychedelic. Yet for an hour and a half, these two people will become so important to you. Your heart aches for them, and you believe, well, everything. Everything. The feeling you get from watching Sunrise is a microcosm of the way cinema burns into your heart. This is an indescribable feeling of majesty and beauty, tailored by the film to match. In 1924 Murnau made The Last Laugh (Murnau, 1924), another film marked by its overwhelming visual beauty and emotional heft. The doorman (Emil Jannings in his best performance with Murnau) is the best character in Murnau's catalog, instantly sympathetic and likeable, and the film becomes one of the best stories ever told about aging and falling out of place. What makes the film really special, however, is its visual fluidity. Told almost entirely without title cards, The Last Laugh is a feast for the eyes. The techniques used in this film continue to push the art form forward. Murnau and cinematographer Karl Freund went to any means necessary to get the most interesting shot possible in every scene. Playing with putting the camera on a bicycle and roller skates, superimposing shots of miniatures into the frame and putting the actors on pendulums and under distorted glass. It’s this type of experimentation that excites filmmakers, and pushes film as a genuine art form. Distorting and emphasizing film grammar in this way, makes room in the future for further cinematic experimentation and appreciation, and moves the medium into new avenues and with the vigor of future auteurs. After an all-too-brief pitstop with the hour-long Tartuffe (Murnau, 1925), a wonderful comedy about class consciousness, religion, and female sexuality that plays with Buster Keaton-esque fourth wall breaks, sight gags, and deconstruction of film grammar, Murnau made Faust. Faust is peak German expressionism and is perhaps the most visually stunning movie ever made. It is certainly one of them. The experience of watching Faust for the first time is almost as biblical as the subject matter. It is a perfect synthesis of what makes silent films so special, the art form has arguably never been matched in terms of sheer visceral storytelling since Faust came out. You will feel the pain, the hatred, the love, the wonder, all of it. This one is really special. Cinema in its purest form. It is worth noting that after Faust and Sunrise Murnau made 4 Devils, perhaps the greatest of all lost films. A film whose only copy was allegedly tossed into the ocean by actress Mary Duncan, although the validity of this seems far-fetched. The film is not available to watch, but we can get a bittersweet taste of what the film may have looked like through the tireless efforts of film historian Janet Bergstrom to bring awareness to the tragic loss of this film. The documentary Murnau's 4 Devils: Traces of a Lost Film, provides sketches, behind the scenes photos, and contemporary audience reactions. By all measure, this film seems like it is the climactic peak of silent visual storytelling, and its loss is a major black void in our shared cinematic legacy. It is a necessary piece to finish our cinematic puzzle whose whereabouts need to be tracked down. One of Murnau's absolute best films, and the greatest discovery when researching him, The Burning Soil (Murnau, 1922), is not lost but it is close. It was released the same week as Nosferatu (Murnau, 1922), While that movie is a true and deserved icon of cinema, The Burning Soil has basically disappeared, despite being arguably just as good. The only copy that exists is a bootleg VHS rip. Part of any Murnau historical research is uncovering a wealth of lost or poorly restored films, because it is so important. How is it that a director can release two genuine masterpieces in the same week and one of them becomes part of the cultural zeitgeist while the other is so badly abused? This is an incredibly rich family drama that feels startlingly similar to a lot of classic movies; a heavy character study that predates stuff like The Godfather (Coppola, 1972) and There Will Be Blood (Anderson, 2007) and deserves to be put in that same category. Murnau’s visual mastery shines through despite the truly horrible quality of the only available print. The films of F.W Murnau are some of the most important treasures we have. Only by making the attempt to restore and track down his marvels can we begin to repair our fractured cinematic legacy. One can’t help but grieve his lost films and buckle under the weight of his surviving masterpieces. Who else could create the hellish horror that comes from the first attack scene in Nosferatu, or the transcendent love when Janet Gaynor and George O’Brian float through the city traffic in Sunrise?

About the Creator

Rowan Harper

Rowan Harper is a Colorado-based filmmaker, film critic/historian, and lifelong lover of the arts. Rowan's career includes extensive experience as an actor, director, producer, stagehand, and awarded musician in both film and live theater.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.