"O, full of scorpions is my mind!"

Shakespeare's Language of Thematic Madness

Background and Context:

Check out the other Shakespeare articles for the full story. I'm frankly kind of sick of typing it out.

"O, full of scorpions is my mind!"

Shakespeare's Language of Thematic Madness

Madness is a recurring and complex theme in Shakespeare’s works, often serving as a vehicle for exploring the human psyche, the fragility of power, and the boundaries between reason and chaos. While some of his characters exhibit genuine psychological distress, others wield the language of madness as a tool for survival, manipulation, or self-expression.

I will examine how Shakespeare portrays madness through language, drawing on examples from Hamlet, King Lear, Macbeth, Othello, and Richard III. Rather than discussing individual plays in isolation, I explore key thematic concerns such as: the performance of madness, the fragmentation of speech, and the connection between madness and prophecy.

Language is Shakespeare’s primary means of portraying madness, often reflecting a character’s deteriorating state of mind through disrupted syntax (sentence structure), repetition, wordplay, and imagery. As scholars such as Greenblatt (2004) and Showalter (1985) have argued, Shakespeare’s linguistic choices not only illustrate psychological disorder but also invite the audience to question whether madness is a condition of the mind or a response to external pressures.

In Hamlet, for instance, the Prince’s erratic language blurs the boundaries between feigned and real insanity, while King Lear’s descent into madness is marked by disjointed, prophetic speech. Similarly, Lady Macbeth’s obsessive hand-washing in her sleepwalking scene (Macbeth, Act 5, Scene 1) embodies guilt-induced psychological collapse, articulated through fragmented phrases.

Madness as Performance

Shakespeare’s portrayal of madness often blurs the line between reality and performance. Some characters consciously adopt the guise of madness as a strategic tool, while others descend into madness without awareness of their own unraveling. This distinction is central to Hamlet and King Lear, where the protagonists’ relationships with their supposed insanity shape their respective tragedies. Hamlet’s madness is, at least initially, a deliberate act designed to mislead others, whereas Lear’s descent into madness is genuine, marked by a loss of control over language and self-perception. Shakespeare’s use of soliloquies and asides plays a crucial role in distinguishing between performative and genuine madness, highlighting how language can be both a mask and a mirror for psychological turmoil.

Hamlet’s calculated performance of madness is established early in Hamlet when he tells Horatio that he will "put an antic disposition on" (1.5.171). His erratic speech patterns, witty wordplay, and seemingly nonsensical exchanges with Polonius and Claudius create an aura of unpredictability that serves to obscure his true intentions. As Greenblatt (2004) notes, Hamlet’s linguistic chaos is not merely a sign of instability but a tool of resistance against the deceptive court of Elsinore. His soliloquies provide insight into his genuine mental state, offering a stark contrast to the disordered language he employs in conversation with others. For instance, in "To be or not to be" (3.1.56), Hamlet’s introspection reveals existential despair rather than madness, suggesting that his most rational thoughts are expressed in private, while his public persona is a carefully constructed performance.

King Lear, on the other hand, does not perform madness intentionally but rather experiences a gradual psychological disintegration. Unlike Hamlet, Lear does not manipulate language to deceive others; instead, his madness is reflected in the breakdown of his speech. His descent is marked by increasingly erratic syntax, fragmented sentences, and prophetic outbursts. When he rages against the storm in Act 3, Scene 2, his address to the elements: "Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks! Rage! Blow!" demonstrates how his language becomes more chaotic as his grip on reality weakens.

Neely (1991) argues that Lear’s madness is both personal and political, reflecting not only his internal turmoil but also the breakdown of kingship and order. Unlike Hamlet, whose soliloquies clarify his true mental state, Lear’s ramblings in the storm scene reveal a genuine detachment from reason, suggesting that his madness is not an act but a loss of self.

The key difference between Hamlet’s and Lear’s linguistic madness lies in their relationship to self-awareness. Hamlet remains conscious of his performance, using language as a means of control, whereas Lear’s linguistic fragmentation reflects his diminishing agency. This distinction is further reinforced by the Fool in King Lear, whose riddles and paradoxes create an ironic contrast with Lear’s descent into genuine madness. As Dollimore (2004) suggests, the Fool serves as a satirical counterpart to Lear, illustrating how madness, whether feigned or real, can expose uncomfortable truths about power and human nature.

Through the interplay of soliloquies, rhetorical shifts, and linguistic breakdowns, Shakespeare presents madness as both an instrument of deception and a condition of suffering. While Hamlet manipulates madness as a mask, Lear is ultimately consumed by it, demonstrating the fine line between performance and reality in Shakespearean tragedy.

Loss of Coherence

Shakespeare frequently conveys madness through the breakdown of language, using disrupted syntax, disjointed speech, and erratic wordplay to reflect characters’ deteriorating states of mind. Unlike the controlled rhetorical flourishes of sanity, Shakespearean madness often collates in linguistic fragmentation, where characters struggle to articulate their thoughts coherently.

This loss of verbal structure parallels their psychological collapse, highlighting the ways in which madness fractures identity and perception. Comparing Lear’s storm speeches, Ophelia’s fragmented songs, and Lady Macbeth’s sleepwalking utterances reveals how Shakespeare tailors the breakdown of language to reflect different types of madness: rage-induced, grief-stricken, and guilt-ridden.

King Lear’s descent into madness is marked by an increasing loss of linguistic coherence. As his authority erodes and he is cast out into the storm, his speech becomes wild, incoherent, and filled with violent imagery. In Act 3, Scene 2, Lear’s famous outburst: "Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks! Rage! Blow!" abandons conventional syntax, relying instead on imperatives and exclamations. His inability to command the storm reflects his own loss of control, both as a ruler and as a rational being.

As Kastan (1999) suggests, Lear’s linguistic fragmentation mirrors the disintegration of the kingdom itself, turning his words into echoes of political and personal collapse. Unlike Hamlet, who weaponises linguistic disorder, Lear’s breakdown is involuntary, demonstrating how his mental state is slipping beyond his own comprehension.

Ophelia’s madness in Hamlet presents a different form of linguistic deterioration. Unlike Lear’s grand, chaotic declamations, Ophelia’s speech fractures into fragmented songs and disjointed phrases. In Act 4, Scene 5, she flits between snatches of nursery rhymes and cryptic allusions: "How should I your true love know / From another one?" blurring the lines between innocence and trauma. Showalter (1985) argues that Ophelia’s madness is deeply gendered, as her speech reflects the powerlessness and repression imposed upon her. Unlike Hamlet, whose verbal disorder is performative and strategic, Ophelia’s language disintegrates into a non-rational form, suggesting a complete psychological rupture rather than a deliberate act.

Lady Macbeth’s sleepwalking scene in Macbeth provides another variation on the theme of linguistic fragmentation. While Ophelia’s songs suggest a descent into childlike regression, Lady Macbeth’s speech is dominated by broken phrases, repetitions, and obsessive fixations. Her famous utterance: "Out, damned spot! Out, I say!" (5.1.35), depicts how guilt manifests through compulsive language. Unlike her earlier speeches, which are characterised by power and persuasion, her fragmented sleepwalking monologue reveals a subconscious unraveling. Neely (1991) suggests that Lady Macbeth’s madness is unique in that it is not external chaos that fractures her speech, but an internalised guilt that escapes in disjointed murmurs.

What unites Lear, Ophelia, and Lady Macbeth is the way their madness erodes their ability to communicate meaningfully. Lear’s storm rants, Ophelia’s singsong mutterings, and Lady Macbeth’s repetitive guilt-ridden whispers all illustrate how madness in Shakespearean tragedy is expressed through linguistic collapse. Whether driven by loss, grief, or guilt, Shakespeare presents madness as the disintegration of structured speech, reflecting the deeper psychological and existential crises faced by his characters.

Delusion, Truth and Prophecy

Shakespeare frequently intertwines madness with prophecy, suggesting that those who appear mad may, paradoxically, have access to hidden truths. Throughout his plays, characters in states of madness or perceived irrationality often articulate insights that rational minds overlook. This dynamic is particularly evident in King Lear, where the Fool’s cryptic wisdom exposes the flaws of authority, and in Macbeth, where the Witches’ ambiguous prophecies exploit Macbeth’s growing instability. The question arises: does madness grant vision, or does it merely create the illusion of prophetic insight? Shakespeare’s treatment of this theme blurs the line between delusion and revelation, raising complex questions about perception and truth.

In King Lear, the Fool serves as a Cassandra-like figure: mocked, dismissed, yet eerily perceptive. Unlike Lear, whose madness is involuntary, the Fool adopts a performative madness that allows him to speak truth without fear of reprisal. His riddles and jests contain profound critiques of power, warning Lear of his folly long before the king realises it himself. For instance, the Fool’s remark: "Thou shouldst not have been old till thou hadst been wise" (1.5.39–40), exposes Lear’s tragic flaw: his inability to distinguish between true loyalty and flattery.

As Kermode (2000) argues, the Fool’s wisdom lies in his detachment from conventional authority, allowing him to articulate truths that remain hidden from those bound by pride and status. However, his disappearance from the play coincides with Lear’s full descent into madness, suggesting that the Fool’s role as a truth-teller is only necessary while Lear still retains some grasp on reality.

A similar ambiguity surrounds the Witches in Macbeth. Their enigmatic prophecies set Macbeth on a path to destruction, but Shakespeare leaves open the question of whether they manipulate him or merely reveal the ambitions already lurking in his mind. The Witches never instruct Macbeth to kill Duncan; they simply greet him with the title "King hereafter" (1.3.50), planting the seed of possibility. Macbeth’s growing instability, marked by hallucinations of daggers and ghosts, suggests that his own mind distorts their words into a justification for his actions.

As Bloom (1998) observes, Macbeth’s madness is not a sudden break but a progressive descent fuelled by an obsessive misinterpretation of prophecy. Unlike Lear, who gains tragic insight through suffering, Macbeth remains trapped in self-delusion, mistaking his own destruction for destiny.

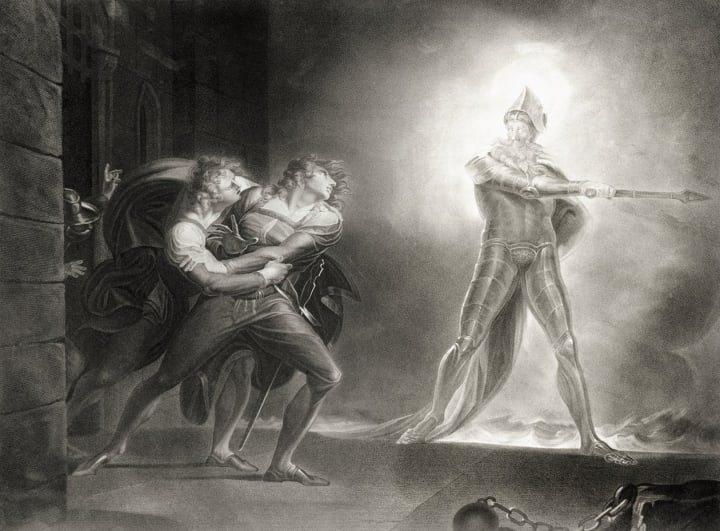

The connection between madness and prophecy is further reinforced by Shakespeare’s use of supernatural or liminal figures. The Fool, the Witches, and even the ghost of Old Hamlet all straddle the boundary between madness and wisdom, revealing truths that challenge conventional perception. In each case, Shakespeare suggests that madness, whether real or feigned, can serve as a conduit for deeper understanding. However, the consequences of such insight vary: Lear ultimately attains tragic clarity, while Macbeth’s inability to interpret prophecy rationally leads to his ruin.

By exploring the connection between madness and prophecy, Shakespeare complicates the notion of rational truth. His plays suggest that those deemed mad may, in fact, perceive reality more clearly than those who consider themselves sane. Yet this vision is often futile, like Cassandra’s doomed prophecies, the insights of Shakespeare’s mad figures frequently go unheard, dismissed as the ravings of the insane. This tragic irony underscores the fragility of truth in a world where reason and madness are often indistinguishable.

Gendered Madness

Shakespeare’s portrayal of madness is deeply gendered, with male and female characters expressing their psychological breakdowns in distinct ways. While male characters such as Lear and Macbeth externalise their madness through grand, chaotic raving, female characters like Ophelia and Lady Macbeth express their distress in more fragmented and internalised ways, often shaped by societal constraints. These differences suggest that Shakespeare not only recognised the ways in which madness was perceived differently in men and women but also used these gendered portrayals to critique power structures and expectations.

Ophelia’s madness in Hamlet is marked by poetic lyricism and passivity, a stark contrast to the calculated verbal playfulness of Hamlet’s feigned madness. Her descent into insanity is expressed through disjointed folk songs and cryptic phrases, as seen in Act 4, Scene 5: “He is dead and gone, lady, / He is dead and gone” (4.5.29–30). Showalter (1985) argues that Ophelia’s madness is constructed as a feminine affliction, linked to lost love and sexual vulnerability. Unlike male figures who rage and threaten, Ophelia is melancholic and incoherent, embodying early modern anxieties about women’s emotional instability. Her madness is not an act of rebellion but one of submission: her inability to resist the forces that control her results in her silent drowning, reinforcing the idea that women’s madness is often equated with victimhood.

Lady Macbeth’s unraveling presents a different but equally gendered depiction of madness. While she begins as a commanding and articulate figure, her psychological deterioration is expressed through compulsive, guilt-ridden repetitions. In the famous sleepwalking scene (5.1), her speech is fragmented and obsessive: “Out, damned spot! Out, I say!” (5.1.35). Unlike Macbeth, whose madness is driven by paranoia and grand hallucinations of fate, Lady Macbeth’s is inward and domestic, fixated on the physical traces of her crime.

Neely (1991) suggests that her madness is symptomatic of the constraints placed upon women in a patriarchal society. She initially usurps traditional gender roles by urging Macbeth to act, yet her breakdown restores her to a conventional position of frailty and hysteria. Her fate, like Ophelia’s, is death by her own hand, reinforcing the notion that female madness in Shakespearean tragedy often leads to self-destruction rather than externalised violence.

By contrast, male madness in Shakespeare is often linked to power and existential crisis. Lear’s raving in King Lear (e.g., “Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks! Rage! Blow!” 3.2.1) is performative and expansive, transforming his personal downfall into a cosmic, almost philosophical tirade. Macbeth’s descent into madness, similarly, is tied to his thirst for power and his fear of losing control. The language of male madness is often rhetorical and outward-facing, filled with interrogatives, commands, and exclamations, whereas female madness is introspective, fragmented, and lyrical.

As Kermode (2000) observes, Shakespeare's male characters struggle with madness in a way that allows them to remain at the centre of political and narrative power, whereas his female characters' madness is a means of silencing and erasure.

Shakespeare’s gendered portrayal of madness, then, is not simply a reflection of early modern views on mental illness but a commentary on the roles assigned to men and women. While Lear and Macbeth rage against their fates in ways that demand attention, Ophelia and Lady Macbeth internalise their suffering, their breakdowns serving as a form of tragic inevitability. By differentiating the language of male and female madness, Shakespeare not only reflects societal attitudes towards gender and mental instability but also critiques the structures that determine whose voices are heard and whose madness is dismissed as mere lamentation.

Tyranny, Madness and Power

Shakespeare frequently explores the intersection of madness and power, illustrating how unchecked ambition, guilt, and fear of loss can drive rulers into psychological disarray. Through characters such as Macbeth, Richard III, and King Lear, he demonstrates how the language of madness and tyranny often overlaps, with paranoia and self-justification becoming key markers of a ruler’s descent. Unlike figures such as Ophelia or Lady Macbeth, whose madness is deeply internalised, the madness of powerful men in Shakespeare’s plays is performative and rhetorical, shaped by their relationship with authority and control.

Macbeth’s descent into madness is intrinsically tied to his ambition and the fear of its consequences. Initially, he is hesitant and full of doubt, yet as he commits more atrocities, his language becomes erratic and fragmented, mirroring his psychological unraveling. His famous soliloquy in Act 5, Scene 5: “It is a tale / Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, / Signifying nothing” (5.5.26–28) reflects his final descent into nihilism, where his words lose coherence and meaning.

As Greenblatt (2018) observes, Macbeth’s language shifts from poetic ambition to disillusioned paranoia, illustrating how tyranny ultimately erodes both reason and identity. His earlier soliloquies, filled with metaphor and internal conflict, contrast sharply with his later speeches, which are dominated by abrupt, fearful outbursts. Shakespeare suggests that power, when sought through ruthless means, leads to a self-destructive form of madness, where paranoia replaces clarity.

Richard III, in contrast, manipulates language to construct an appearance of control, even as his psychological instability becomes more evident. Unlike Macbeth, who agonises over his moral choices, Richard embraces villainy with theatrical confidence. His rhetorical brilliance allows him to deceive others, yet as his grip on power weakens, his language shifts from calculated persuasion to desperate self-justification. In Act 5, Scene 3, he is tormented by the ghosts of those he has killed, crying out, “O coward conscience, how dost thou afflict me!” (5.3.179). Here, Richard’s usual control over language falters, and he begins to speak in disjointed phrases, mirroring the collapse of his authority.

Tennenhouse (1986) argues that Richard’s linguistic power is a key aspect of his tyranny; once his rhetoric fails him, so too does his ability to command fear and loyalty. Shakespeare presents Richard as a figure whose madness is rooted in self-delusion; his linguistic dexterity is a tool of manipulation, but it ultimately unravels as his crimes catch up with him.

King Lear offers a different perspective on madness and power. Unlike Macbeth and Richard, whose madness stems from their ruthless ambition, Lear’s descent is tied to his loss of authority. His language in the storm scene (3.2) is filled with violent imperatives: "Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks! Rage! Blow!” as if he is still trying to command nature itself. However, as he loses his sense of kingship, his language becomes more introspective and philosophical. By the time he reunites with Cordelia, his speech is stripped of grandeur: “Pray you now, forget and forgive; I am old and foolish” (4.7.83).

Kastan (2013) argues that Lear’s madness is paradoxically a path to wisdom. His fall from power allows him to see truth more clearly. Unlike Macbeth and Richard, whose madness leads to destruction, Lear’s descent ultimately brings a form of tragic enlightenment.

Through these characters, Shakespeare illustrates that madness in rulers is deeply intertwined with their relationship to power. Macbeth and Richard III demonstrate how tyranny breeds paranoia, leading to linguistic and psychological collapse. Lear, in contrast, finds clarity in madness, though at a terrible cost. Shakespeare’s treatment of these figures suggests that power is not just a political force but a psychological burden, one that can drive even the most formidable rulers into madness.

Conclusion

Shakespeare’s depiction of madness is deeply rooted in language, with disrupted syntax, rhetorical excess, and fragmented speech serving as key markers of psychological instability. Whether through Hamlet’s calculated linguistic chaos, Lear’s storm-driven tirades, or Lady Macbeth’s fractured sleepwalking soliloquy, Shakespeare uses words to expose the inner turmoil of his characters. His portrayal of madness is never one-dimensional; it is performative, prophetic, gendered, and inextricably linked to power.

An important theme across Shakespeare’s works is how madness can be both destructive and revelatory. For tyrannical figures like Macbeth and Richard III, the descent into madness reflects the corrosive nature of unchecked ambition, where paranoia warps perception and erodes control. In contrast, Lear’s madness leads to self-awareness, highlighting how suffering can illuminate truth. Shakespeare also contrasts male and female expressions of madness, with women’s breakdowns often framed through societal repression and poetic lament, while men’s are tied to dominance and delusion.

Shakespeare’s portrayal of madness remains compelling because it speaks to universal anxieties about: power, identity, and the fragility of reason. His language-driven approach ensures that each character’s descent feels distinct, offering enduring insights into the human psyche. In an era that continues to grapple with mental health and the nature of authority, Shakespeare’s explorations of madness remain as relevant as ever.

Works Cited:

- Bloom, H. (1998) Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. New York: Riverhead Books.

- Dollimore, J. (2004) Radical Tragedy: Religion, Ideology and Power in the Drama of Shakespeare and His Contemporaries. 3rd edn. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Greenblatt, S. (2004) Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Kastan, D. (1999) Shakespeare After Theory. London: Routledge.

- Kermode, F. (2000) Shakespeare’s Language. London: Penguin.

- Neely, C. (1991) Distracted Subjects: Madness and Gender in Shakespeare and Early Modern Culture. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Showalter, E. (1985) The Female Malady: Women, Madness and English Culture, 1830–1980. New York: Pantheon.

- Tennenhouse, L. (1986) Power on Display: The Politics of Shakespeare’s Genres. New York: Methuen.

About the Creator

Annie Kapur

I am:

🙋🏽♀️ Annie

📚 Avid Reader

📝 Reviewer and Commentator

🎓 Post-Grad Millennial (M.A)

***

I have:

📖 280K+ reads on Vocal

🫶🏼 Love for reading & research

🦋/X @AnnieWithBooks

***

🏡 UK

Comments (1)

I chose "Macbeth" for one of my final papers, and it has always been a favourite of mine. I still wonder about that continued trope and how it has bled into our own culture. Madness can exist in many forms, even without a body of water or an ulterior motive.