Little Shop of Horrors: A Lot of Folks Deserve To Die

Is Seymour Krelborn one of them?

I was four years old, lying on my stomach on a blue carpet that smelled like cigarettes, staring up at my family’s boxy 1980’s TV, entranced by the tale unfolding before my eyes. Like my favorite TV show, Sesame Street, the film I was watching utilized complex puppetry to bring magic to the screen. Unlike Sesame Street, this film involved sadomasochism, drug use, dentistry gone awry, and lots and lots of murder.

I was watching Little Shop of Horrors.

Years later, when I asked my mom why she let me watch a PG-13 rated horror movie before I’d entered kindergarten, she told me she’d thought the bad parts would go over my head. She was right about that. My main impressions of the movie were that Audrey was prettier than Barbie, the plant was funny, and Somewhere That’s Green was the best.

My mom also told me that she’d expected me to watch Little Shop once and forget about it. She was wrong.

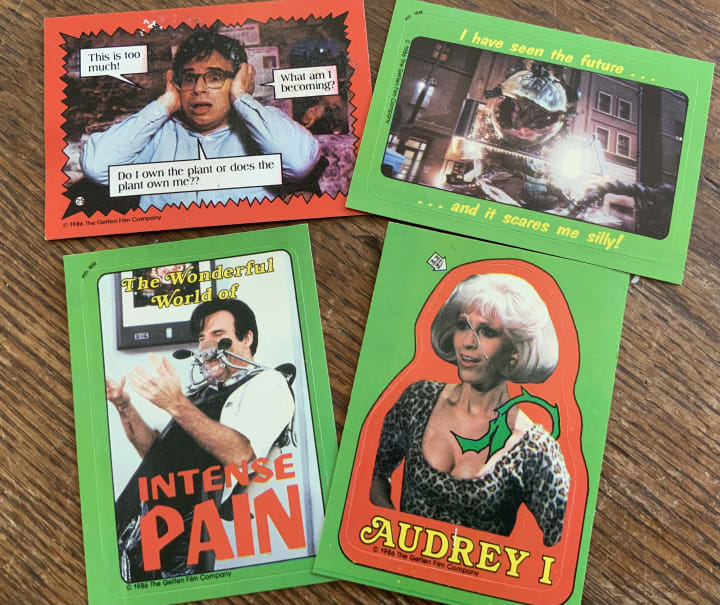

Most small children have one movie they beg to watch over and over until they can recite every word and the family is sick of it. Mine was Little Shop of Horrors. My family had a copy on VHS that’d been taped off the TV, complete with commercials for McDonald’s and RadioShack and a heartwarming Christmas movie staring OJ Simpson. During my near daily journeys into the world of Mushnik’s skid row flower shop, I’d sing along with every song, from the show stopping Suddenly Seymour, to the rather less inspiring advertising jingles that I was still too young to recognize as separate from the movie itself.

My Little Shop of Horrors obsession continued until second grade, when I got in trouble for belting Mean Green Mother From Outer Space to myself as I swung back and forth on the school swing set during recess. The teacher watching me didn’t like the line about busting Seymour’s balls, or the shaky “oh shit” that ended the song. I won’t say that I gave up Little Shop of Horrors without a fight, and I certainly never forgot it, but the adults in my life managed to steer my obsessive tendencies in somewhat less creepy directions.

For a little while, at least.

I revisited Little Shop of Horrors as a teen in the year 2003, when a revival opened on Broadway. I was a huge Broadway fan by then, so of course I bought the newly released cast recording. I learned that in the stage version of the show, rather than defeating the Audrey II and living happily ever after, Audrey and Seymour died horrible deaths, leaving the plant to propagate and destroy the world. I was nonplussed. I had other things on my mind.

Then, in late 2019, stuck at home as the world dealt with the first throes of the Covid-19 pandemic, in need of some comfort amidst all the craziness, I decided to watch Little Shop for the first time in more than twenty years. I had a copy a friend had pirated for me, and I started it up, smiling at how I still knew every line, and at how I remembered exactly where the commercial breaks had been. It was a joyful and much needed burst of nostalgia, until the film reached its final scenes.

My friend had unknowingly downloaded the Little Shop of Horror’s director’s cut, released in 2012– something I hadn’t realized existed. This version of Little Shop of Horrors featured a different ending than the film as it had been released in 1986. It featured the intended ending, an ending that had been scrapped and hastily re-written because test audiences found it too upsetting.

As I sat in bed, bent over my IPad, I watched my childhood heroes die. Audrey went first, chomped to death beneath the plant’s jaws. Seymour followed, cowering in fear and surrounded by rubble. I recognized the songs that accompanied this carnage from the 2004 CD, but the visceral horror I felt at seeing them performed was new. I was an adult in my thirties who’d watched Little Shop of Horrors without flinching at the age of four, but seeing the movie end this way brought me to tears and left me unsettled and nauseous.

Even so, I wanted more.

Since then that day, I’ve watched several bootlegs of stage versions of Little Shop of Horrors. I’ve found that none of them were upsetting, though they all ended with the demise of the characters I love. Two weeks ago, I was blessed with the chance to travel to New York to see the current off-Broadway production, with Jeremy Jordan as Seymour. The same ending that had horrified me in the film left me grinning ear to ear underneath my KN-95 mask.

I’ve been thinking constantly about why my reaction to the deaths of Audrey and Seymour in the the stage version of Little Shop of Horrors is so different than my reaction to the same characters dying in the film.

Some people might attribute my feelings to the film’s place in my childhood. Presumably, most people would be uncomfortable if they sat down to rewatch the Lion King, or Mary Poppins, or whatever movie kids normally become attached to, and were greeted with a surprise bloodbath in place of the anticipated happy ending.

Frank Oz, the director of Little Shop of Horrors, explained how he thought test audiences for the movie had disliked the ending he’d first envisioned, because movies don’t end with the cast coming out for their final bows. He described the phenomenon thusly: “"I learned a lesson: in a stage play, you kill the leads and they come out for a bow—in a movie, they don't come out for a bow, they're dead. They're gone and so the audience lost the people they loved, as opposed to the theater audience where they knew the two people who played Audrey and Seymour were still alive. They loved those people, and they hated us for it."

However, I think my differing reactions (and perhaps the reactions of others) to the deaths of Seymour and Audrey in the film and stage versions of Little Shop of Horrors have more to do with script differences and acting choices than they do with nostalgia and whether or not the actors come out to bow.

Here are a few of the factors that made me comfortable with the characters dying on stage but not on screen:

Humor

Although the film and stage versions of Little Shop of Horrors are both classified as musical comedies, the stage show plays more for laughs while the film ekes more drama out of Seymour and Audrey’s plight.

This can be seen as early as the second musical number in the show, Skid Row (Downtown). In the off-Broadway production I saw, Christian Borle stole the scene, portraying a hilarious chorus of losers and vagrants and drawing laughs from the audience. In the film, the camera angles highlighted the dismal grit of Skid Row’s dirty streets, and Rick Moranis as Seymour sang about his dream to escape his depressing life while facing a chainlink fence resembling prison bars.

When stage Seymour talks to Audrey about the life he led up until he found botanical success with the Audrey II, the hardships he recounts are too hyperbolically awful to be taken seriously, hinging on how Mr. Mushnik makes him sleep under the shop counter. Rather than pitying him and rooting for him to find a better life, the audience giggles.

There are entire comedic numbers in the stage show, such as Mushnik and Son, which are replaced with dramatic dialogue in the movie.

The stage show is slapstick— smart slapstick with Faustian allusions, but slapstick nonetheless. In the end, watching the characters die feels similar to watching Loony Toons characters die. It’s all part of the fun. The movie characters feel more like people, so it hurts to lose them.

Agency

Stage Seymour has agency that his film counterpart lacks. In both the stage and film versions of Little Shop of Horrors, Seymour helps the plant consume its first victim, Audrey’s sadistic dentist boyfriend. In both version, Seymour doesn’t technically murder the dentist, but instead watches and fails to help as he accidentally asphyxiates himself on nitrous oxide. In the stage version, the characters sing a duet in which the dentist begs for help and Seymour weighs the moral and ethical consequences of whether or not to save his life. In the film, Seymour spends the entire scene curled up in his chair, clearly too terrified to speak or move, frozen in inaction. After he chops up the dentist and feeds him to the plant, he’s shown alone in his room, rocking himself back and forth in traumatized fear.

Later, when the time comes for Seymour to off Mr. Mushnik for the the sake of self-preservation, the stage version of the character directs Mushnik to go over to the plant and knock on its pod. He knows what he’s doing. The movie version once again plays the role of a stunned innocent, watching with wide eyes and biting down on his hand to keep from screaming as Mr. Mushnik backs almost accidentally into the plant’s mouth.

When stage Seymour finally gets eaten by the plant, he goes out swinging. After trying several methods to kill the plant, he willingly climbs inside of it, brandishing an ax and proclaiming that he’s going to hack it to bits from the inside. Meanwhile, in the film, as the film plant sings a rousing number about its evil plans (Mean Green Mother From Outer Space, written especially for the movie), Seymour curls up in a fetal position in the corner of the rubble which used to be the Little Shop, having attempted to commit suicide one scene earlier. After pulling down Seymour’s pants and making a couple of (funny??) attempts to punch him in the dick, the plant devours him while he’s too helpless and frightened to resist.

The final result is that stage Seymour feels like he deserves to be eaten. The choices that led to the plant growing out of control were his own. He gets his moment of strength and redemption at the very end. Film Seymour never got to decide anything or have his final show of strength. His death feels sad and unearned.

Spectacle

The spectacle factor is easy to explain. As cool as the plant puppet in the Little Shop of Horrors film is, seeing that kind of stagecraft live is way cooler. The Audrey II is the sort of spectacle that can overshadow anything else that may be going on.

I saw the stage production from the second row of the theatre. During the finale, Don’t Feed the Plants, the plant moved forward into the audience. It was so vital and exhilarating that I was past the point of caring what happened to Seymour and Audrey. Judging from the rapturous applause around me, the rest of the audience felt the same way. That’s the kind of feeling that can’t be recreated in a film.

Luckily, the film had another way to make the audience leave the experience feeling happy and exhilarated. This was, of course, by allowing Audrey and Seymour to triumph over the plant.

Little Shop of Horrors is, after all, a story that pits good against evil. Letting evil win is a risky decision in any piece of media. The stage version of Little Shop of Horrors hit the right note to make evil’s triumph natural and satisfying, then wrapped it all up in a burst of stage magic. The film didn’t do that.

That’s why, ultimately, I feel the darker ending worked best for the stage, and the lighter one worked best for the film.

That said, my four-year-old self would probably accuse me of over-analyzing things. She was just in it for the songs.

If you enjoyed reading this, consider sharing it with a friend or over social media.<3

About the Creator

Rose

This is just a hobby.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.