'Ichi the Killer:' Deconstructing the Cool of Violence'

Ichi the Killer is the classic on the newest edition of the Everyone's a Critic Movie Review Podcast.

Ichi the Killer is the classic on the latest episode of the Everyone’s a Critic Movie Review Podcast. I must admit, the work of director Takashi Miike is a blind spot for me. I haven’t intentionally avoided Miike’s brand of ultra-violent spectacle, I just haven’t taken the time to expose myself to it. Thus, this week, looking at Ichi the Killer was an eye opener for me. This bizarre bit of violent nonsense is both nauseating and very intelligent, two feelings that I am struggling to balance positively and negatively.

Is Ichi the Killer a good movie? I’m not sure, but in this article, I will explore how that doesn’t really matter. The reality of Ichi the Killer, what makes it so memorable, is not the gloriously exploitative violence or goofy looking, low rent gore. Rather, it’s Miike’s extremely intelligent deconstruction of how we’ve become so remarkably desensitized to extreme violence. Ichi the Killer, as a character is not an avatar you want as a fan of violent films, he’s the avatar that Miike sees when he looks out at a world gone mad for ultra-violence.

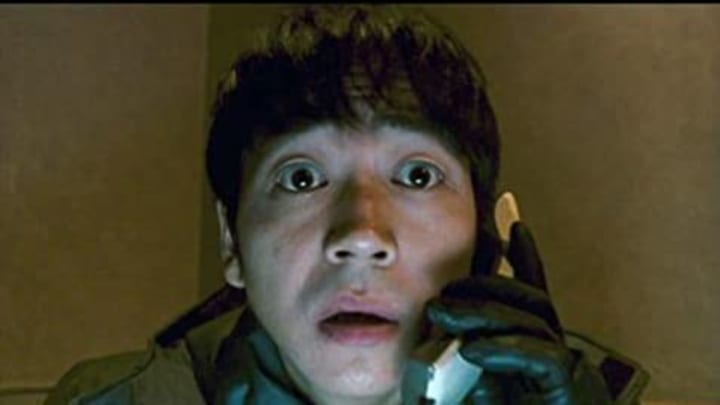

One of the misconceptions I had going into Ichi the Killer was that Ichi was going to be some cool, badass hired assassin type. I assumed that the character of Ichi would be a John Wick-like character who breezes through violent scenarios unrepentant and unruffled by the violence he enacts on others. The movie dismisses this notion right away. The first time we sort of meet the protagonist of the title, he’s orgasming over watching a brutal rape that he does nothing to stop.

The introduction to Ichi the Killer concludes in a nausea inducing scene wherein Ichi’s presence is discovered by the rapist but, by the time he reaches the window through which Ichi was watching him assault a woman, Ichi is gone, leaving only a prodigious amount of semen puddled upon a plant which drips to the ground in full observance of the camera which then witnesses the emergence of the film’s title.

It's a grossout shocker of a start but one that ties violence and sexual release inextricably, a thesis statement for the rest of the movie. Director Takashi Miike wants you to remember how violence and pleasure have become woven together in our society to the point that extreme violence causes the character of Ichi to reach sexual release. In fact, for the rest of the movie, both Ichi and the ostensible villian, Kakihara, express their frustration over the inability to reach sexual climax without violence.

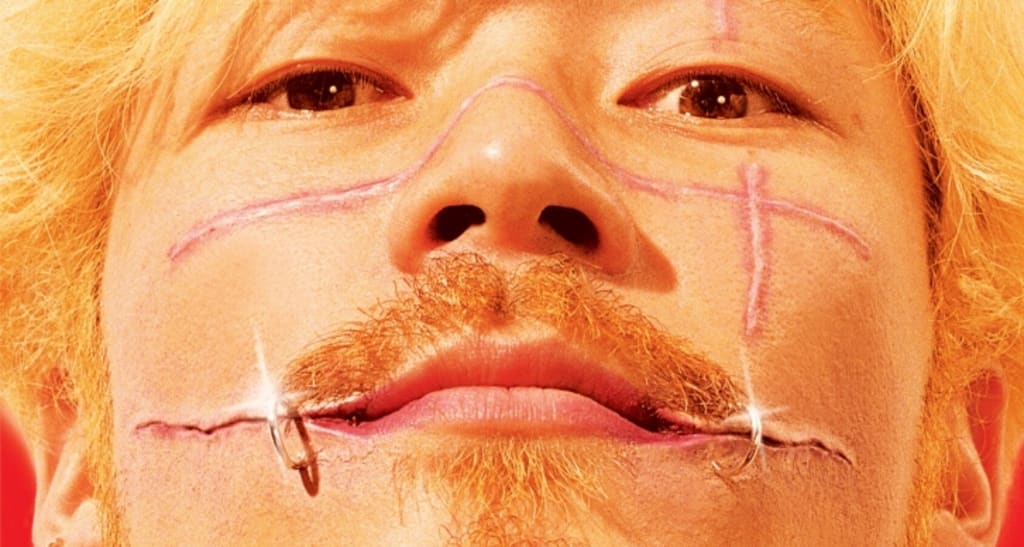

From there, we only eventually meet Ichi who turns out to be a manchild, a severely emotionally disturbed young man who is being manipulated into violence by ‘The Old Man.’ Ichi wears a suit that protects him from harm and is outfitted with blades that can cut a body in half from head to crotch in seconds. And to complete the picture of pathetic, empty vessel of impotent violence, Ichi both gets aroused by violence and becomes a crying whimpering mess when enacting his violence.

I say all of this because I am rather impressed by Miike’s bold depiction here. Robbing the audience of the ability to relate to the protagonist of the title and his acts of extreme violence forces the audience to then only confront the violence. Usually, cool-headed heroes in movies allow us a distance from the violence, an avatar to enact fantasy through. No one would want Ichi as an avatar and thus we are left with the confrontationally severe repercussions of violence and none of the thrill of fantasy.

Yes, the violence is cheesily rendered in some seriously low rent effects but the human limbs and innards on display still carry a little gross out weight to them. At once point, a character holds up a human spine, impressed at how Ichi removed it whole and intact from a body. It’s an effectively ghastly visual even as the fake plastic spine drips with obvious fake blood into gooey puddles on the floor.

But that’s just scenery, the point of the scene is to cast this character holding the spine, the actual protagonist of the movie, Kakihara (Tadonobu Asano), as the audience avatar, a man so desensitized to violence that he has no compunction holding up a spine and being impressed by it. Kakihara can only be turned on by extreme violence, nothing else can give him pleasure. He’s become so used to violence that he feels the absence of violence as one might feel the absence of love.

On the surface, Kakihara is the villain of Ichi the Killer. He’s a mob enforcer seeking revenge against Ichi for killing Kakihara’s boss. But since Ichi isn’t a hero, and we spend most of our time following Kakihara, the roles are slightly reversed. No, Kakihara isn’t a good guy or even an anti-hero, he’s a blatant monster. But, he’s far more of an audience surrogate than Ichi is and settles into that role almost by default.

The lack of a center in Ichi the Killer is a daring story choice. There is literally no one in Ichi the Killer for us to grab onto as anything we recognize from a traditional action movie narrative. This forces us to examine Miike’s ideas rather than distance ourselves from them via our fantasies of power through acts of extreme violence. Unlike American action movies where we are invited to pretend to be Schwarzenegger, Stallone or Seagal, Ichi the Killer leaves us only with the violence, only the blood and guts to relate to and it’s a harsh effect.

It’s a wildly clever way to challenge an audience. It takes the idea of an action movie to its most extreme and dares you to find a way to enjoy it. Some are able to laugh at the extreme special effects and the cheesy execution of such, but you cannot deify these characters the way you would in an American action movie. There are no good guys here, only weirdos and creeps enacting violence to extremes. It’s entirely up to you to find a way to enjoy it and deal with how that reveals you as a person.

I cannot say I ‘enjoyed’ Ichi the Killer in any traditional sense. I appreciate however, what I believe Takashi Miike is trying to say with Ichi the Killer. The message is about violence for the sake of violence and the extreme desentization that violent movies have wrought upon our culture. The characters in Ichi the Killer are the extreme result of a culture that doesn’t take violence seriously and laughs off what would be the ultimate result of the kind of violence we consume.

The reality of being exposed constantly to extreme violence is a detachment from violence so extreme that you might enjoy Ichi the Killer. Ichi as a character is one so warped by the violence that he’s experienced that he can only take pleasure in the extremes. Ichi gets sexually aroused watching women be tortured and raped, he doesn’t seek to punish the rapists when he kills them, he wants to replace them. So warped is Ichi that after he rescues a woman from a violent attack he reassures her that now that the evil man is gone, Ichi himself will abuse and murder her, as if he believes that violence and death is what she wants.

Once again, the idea here is that when you are so often exposed to extreme violence you come to believe that this is what people want, violence. It's a warped idea for a warped culture. Ichi is the result of a society that has deified violence to such a ludicrous degree that we see violence as the product that the masses are seeking rather than what is supposed to result from such violence. The message of violence in movies is lost on a generation of young men who get excited by the explosion and forget why the explosion was viewed as necessary.

Kakihara is another extreme, he can only feel pleasure from extreme violence, violence that he uses as a cover for homo-erotic tendencies. It’s not stated that Kakihara is gay but there is a particular coding happening with the character. Kakihara is extremely flamboyant in his dress and affectation. He enjoys being violently tortured but only by his late Boss whom he claims carried love in his violence.

Kakihara isn’t angry at Ichi for killing his boss, he’s intrigued and turned on by the idea of someone who might be able to give him a sexual release via extraordinary violence and even his own death. There is a deep element of shame in Kakihara that he doesn’t acknowledge. Deep down, he doesn’t just admire Ichi’s extreme violence, he’s turned on by it and knowing this, makes him borderline suicidal. The strong implication is that Kakihara is gay and that his identification with Ichi is an expression of the same devotion that audiences give to our lumbering, muscled up action heroes.

Kakihara deifies Ichi in the way audiences deified people like Stallone, Schwarzenegger and Seagal during their heydays. Thus, in the climax, when Kakihara finally meets his hero and can see his violence firsthand, he’s deeply disappointed at how frail and human Ichi actually is. Ichi is rendered a pathetic mess by enacting violence and this leads to Kakihara essentially taking his own life, unable to cope with the despairing emptiness of the violence he assumed would fulfill his fantasies.

There is a beautifully symbolic aspect of Ichi the Killer that I haven’t touched on yet but is the stone foundation of my observation of Ichi the Killer as a deconstructionist masterwork. Director Shinya Tsukamoto is cast in Ichi the Killer as ‘The Old Man.’ The Old Man is a character who manipulates all of the action in Ichi the Killer. He is the one who turned Ichi into the killing machine that he is. He is the one who puts Kakihara and Ichi on a collision course and along the way, The Old Man is responsible for every important development in the movie.

This is deeply symbolic for Director Takashi Miike as he cites Tsukamoto as an influence on his own career as a director. Tsukamoto rose to fame as a director in the mid-1970s and by the 80's and 90's was venerated for his violent epics such as Tetsuo: The Iron Man, Tokyo Fist, and Bullet Ballet. To have Tsukamoto on board as the ‘director’ of all of the action in the story of Ichi the Killer is a supremely clever piece of casting. If you were to consider Ichi as Miike’s own avatar and Tsukamoto as the one directing Ichi, the symmetry is wildly clever. Ichi is the extreme result of the influences that Miike himself grew up with.

Ichi is a cautionary tale of the endless deification of violence in media. Ichi is what could happen if society wasn’t course corrected away from treating violence as something to aspire to or something to hold out as entertainment. And, in a coincidental way, Ichi the Killer came along at a time when we were moving away from action spectacle and into a less macho-centric version of action movie. The action heroes of the past soon gave way, in the late 90s and early 2000s, to the Jackie Chan’s of the world whose violence was less about the resulting death of bad guys and more about the comic nature of such extreme violence.

Did Ichi cause our society to change and reject action for the sake of action? Violence for the sake of violence? No, not really. Rather, Ichi the Killer provides a signpost today of the shift in our worldwide culture. Retroactively, we can look back on Ichi the Killer as a symbol of where we were as a culture in relation to extreme violence. Before Ichi was a time when we paid no mind to the end result of bullets, explosions and endless, deadly fight scenes.

Since Ichi the Killer, our extreme distance from and treatment of violence as entertainment has led to a different extreme, one of indifference. Lately, a week rarely goes by in America without some sort of violent act that shocks the nation, or is said to shock us. Instead of being shocked, we are mostly apathetic. We could act in many different ways to stop or prevent extreme violence but instead, we merely read about it and move on with our lives.

Instead of a world, envisioned by Miike where we are turned on by violence, we've grown detached in a more apathetic fashion. Instead of trying for gun control or protesting against violence, we watch from the sidelines and hope not to get hit by stray bullets. Violence remains a spectacle in many ways but not one that excites us to sexual levels of pleasure, but rather one that has left us tired, defeated and bordering on indifferent.

Like A Clockwork Orange and Fight Club before it, Ichi the Killer was/is a cry in the wilderness, an unheard call to action. These are movies that tried to tell us where we were headed if we didn't start to treat violence as something other than mindless entertainment. We didn't listen and now we are at a pretty incredible crossroads. Either we will finally snap out of our stupor and do something about real life violence or we will continue to treat violence as another form of entertainment, one devoid of pleasure but ever present.

About the Creator

Sean Patrick

Hello, my name is Sean Patrick He/Him, and I am a film critic and podcast host for the I Hate Critics Movie Review Podcast I am a voting member of the Critics Choice Association, the group behind the annual Critics Choice Awards.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.