Frederick Forsyth, The Dogs of War, and the writer who blurred research and reality

How Frederick Forsyth’s Wild Research Turned The Dogs of War Into a Thriller — and a How-To for Real Mercenaries

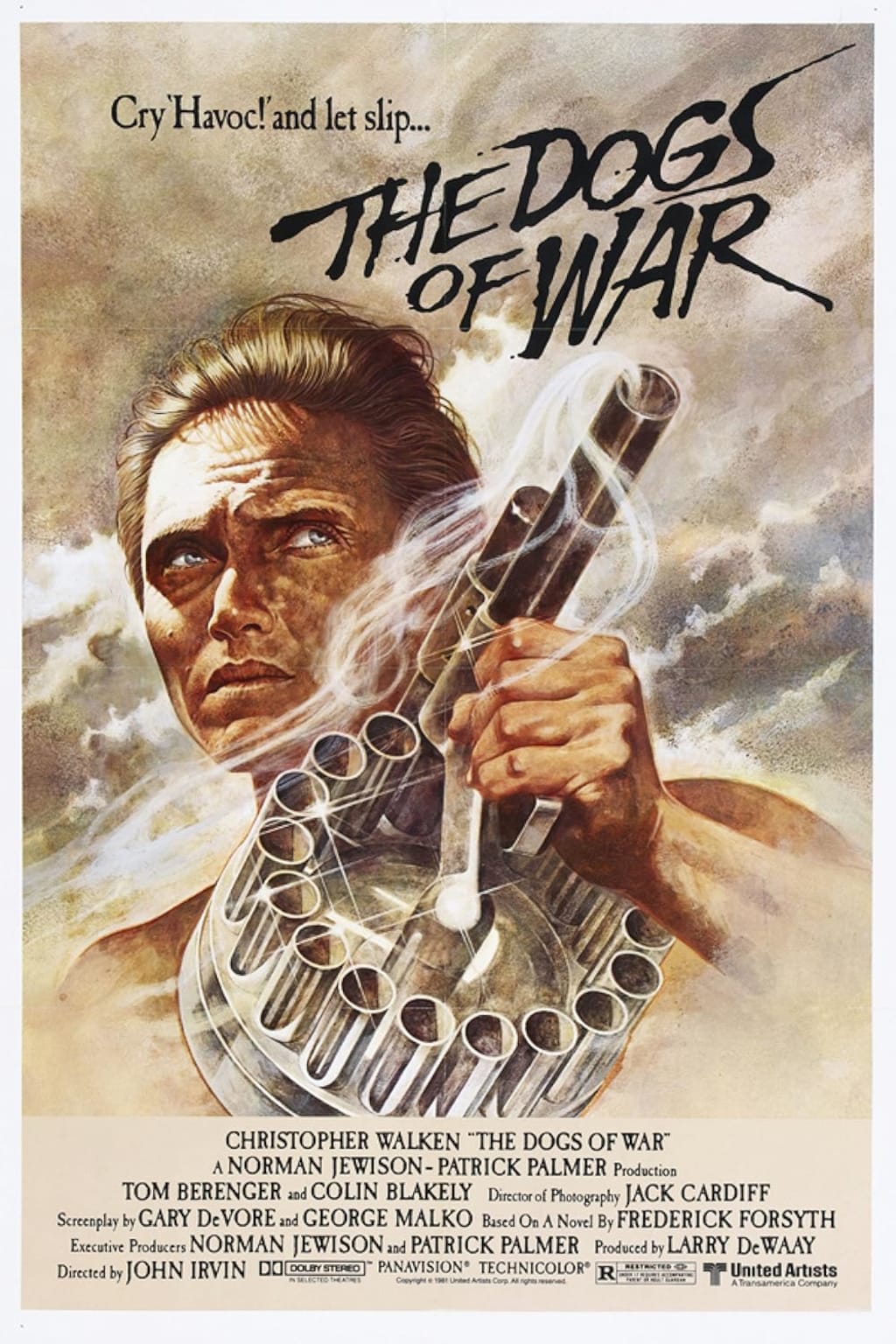

Frederick Forsyth used undercover reporting, intelligence contacts and audacious stunts while researching The Dogs of War. That immersion gave the 1974 novel — and the 1980 film — a cold, operational realism that resonated with readers and, alarmingly, inspired real-world coup plots.

The journalist who wrote like an operations manual

Frederick Forsyth made his name by grafting the precision of a foreign correspondent onto high-tension thriller plots. A former RAF pilot turned BBC and Reuters reporter, Forsyth reported from Biafra and other hot spots; later he acknowledged long ties as an asset/informant for British intelligence — a background that shaped both his methods and his voice. Those credentials explain why his fiction reads less like invention and more like field notes.

Research that read like provocation

Forsyth’s research for The Dogs of War (1974) has become the stuff of legend. He later admitted to posing as someone arranging a coup against Equatorial Guinea in order to get close to mercenaries and arms dealers — an immersion that reportedly produced concrete price estimates (often reported in press accounts as around $200–240k) and operational detail that populate his novel. That stunt prompted press speculation that he’d actually commissioned a plot; archival material and press coverage from the era show genuine coups and coup-planning in the region not long after.

From novel to set: how Hollywood translated the circulation of real weapons and money

Hollywood bought the rights quickly. The Dogs of War’s path to the screen was a long, star-studded shuffle: rights purchased in the mid-1970s, multiple writers and directors attached at different stages (Don Siegel, Norman Jewison, Michael Cimino among those linked), and finally John Irvin directing the 1980 production with Christopher Walken in the lead. Because filming in Africa was considered too risky, Belize and Central American locations doubled for Forsyth’s fictional Zangaro — preserving the book’s tropical, improvisational feel even while sanitizing the real-world danger.

When fiction becomes a blueprint

The darker legacy is that Forsyth’s granular “how” sometimes read as instruction. Investigations into later coup attempts and mercenary operations — most infamously the 2004 “Wonga coup” involving Simon Mann and others attempting to seize power in Equatorial Guinea — referenced playbooks eerily similar to Forsyth’s step-by-step sequencing: recruitment, pay, logistics, and the market for mineral concessions. Commentators, academics and intelligence historians have pointed out that while Forsyth wrote fiction, elements of his depiction were lifted by opportunists seeking practical guidance.

The ethics of immersion

Forsyth’s willingness to pose as a would-be coup backer, leverage intelligence relationships, and cozy up to mercenaries reads differently depending on your frame: bold journalism that produced unmatched authenticity, or ethically dubious immersion that blurred legal and moral lines. The result — a novel and a movie that feel dangerously plausible — is a reminder that meticulous research can create powerfully realistic fiction, and that realism in the wrong hands can be mobilized for harm.

Why the book and film still matter

Today, with mercenary firms and private security companies back in the headlines, The Dogs of War is both historical artifact and cautionary tale: a work of fiction forged in the crucible of frontline reporting that nevertheless fed back into the real-world markets it depicted. The film’s lean, logistical adaptation preserved that uneasy documentary flavor — and cemented Forsyth’s reputation as the thriller writer who didn’t merely imagine operations, he had the contacts to make them feel real.

⸻

Timeline — research → publication → film (key sources)

• Early 1970s — Forsyth’s reporting & MI6 ties: Forsyth reports from Biafra, later acknowledges long-term work as an intelligence asset. Sources: Guardian profile/obituary; Forsyth interviews.

• 1973 — real coups and foiled plots in the region: Spanish arrests and Gibraltar plots are recorded in archival summaries; contemporaneous press and later National Archives material note coup activity around Equatorial Guinea. (See National Archives guidance and historical summaries.)

• 1974 — The Dogs of War (novel) published: Forsyth publishes the mercenary thriller; research anecdotes (posing as coup backer, price quoted) enter public lore.

• Mid-1970s → 1980 — rights & production history: United Artists buys rights (mid-1970s); multiple writers/directors attached; principal photography begins Feb 18, 1980; film released 1980/1981 with John Irvin directing and Christopher Walken starring (filmed largely in Belize).

• 2004 → 2006 — Wonga coup attempt & aftermath: Simon Mann’s failed mercenary expedition to Equatorial Guinea (arrested in Zimbabwe in 2004) is widely reported; Roberts and New Yorker investigations connect the plot’s inspiration to Forsyth’s book.

Do you love the Movies of the 80s? Subscribe to Movies of the 80s on YouTube for more of the greatest and the most forgotten movies of the greatest decade ever.

About the Creator

Movies of the 80s

We love the 1980s. Everything on this page is all about movies of the 1980s. Starting in 1980 and working our way the decade, we are preserving the stories and movies of the greatest decade, the 80s. https://www.youtube.com/@Moviesofthe80s

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.