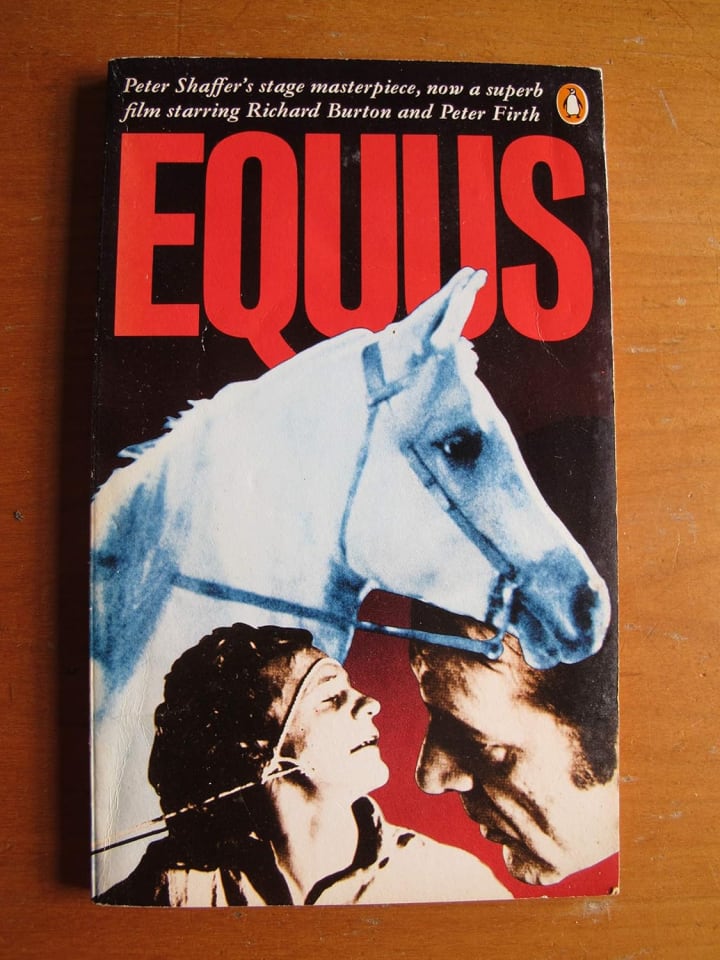

Equus by Peter Shaffer

Why It's a Masterpiece (Week 61)

Peter Shaffer’s Equus was first staged in 1973 at London’s National Theatre under the directorial vision of John Dexter. Inspired by a true story Shaffer had heard about a young boy’s pathological blinding of six horses, he crafted a play that interrogates the psychological underpinnings of worship, repression, and obsession. Shaffer’s unique approach blended psychology with mythology, presenting Equus as a haunting exploration of the human psyche and societal norms.

The play was published in 1974 by André Deutsch in the UK, followed by its American publication by Charles Scribner’s Sons. The text has since become a staple in academic and theatrical circles, studied for its rich thematic content and powerful language. Subsequent revivals, including a notable 2007 West End production starring Daniel Radcliffe, have reintroduced Equus to new generations, ensuring its continued legacy in modern theatre. Shaffer’s complex exploration of religion, sexuality, and psychiatry in Equus remains relevant, resonating with audiences as a seminal work in 20th-century drama.

Plot

Equus follows the story of Dr Martin Dysart, a psychiatrist, and his teenage patient, Alan Strang, who has been court-mandated for treatment after blinding six horses in a stable where he worked. The narrative begins with Dysart’s contemplation of his work in psychiatry, questioning the purpose and value of his profession. Dysart is intrigued and disturbed by Alan’s case, sensing the depths of pain and fanaticism underlying the boy’s actions.

As Dysart delves into Alan’s history, he uncovers layers of parental influence, religious fervour, and psychological complexity. Alan’s father, Frank, is a strict atheist, while his mother, Dora, is a devout Christian, creating a tense household atmosphere that leaves Alan struggling to reconcile conflicting beliefs. Dysart learns that Alan developed a fascination with horses as a child, seeing them as powerful, almost divine creatures. His fixation grows into a quasi-religious worship, symbolised by his invented deity, “Equus,” which embodies both love and fear. This equine god becomes central to Alan’s internal world, representing both transcendence and punishment.

Through hypnosis and investigative questioning, Dysart uncovers the disturbing intimacy Alan had developed with the horses, particularly a stallion named Nugget. Alan’s worship of Equus transcends admiration, leading to private rituals and encounters that border on the erotic. When his relationship with Jill, a young woman at the stable, challenges his understanding of sexuality and loyalty to Equus, Alan’s psychological balance unravels. In a desperate attempt to reconcile his feelings of betrayal and shame, he blinds the horses, believing it is the only way to atone.

Dysart becomes conflicted about his role as a healer. He realises that curing Alan means stripping away the passion that gives his life meaning, a passion Dysart himself lacks. The play ends ambiguously, with Dysart pondering the value of “curing” patients by conforming them to societal norms. He envies Alan’s fervour, however destructive, as he confronts the emptiness in his own life, questioning whether conventional “sanity” is worth the loss of true, albeit painful, individuality.

Into the Book

Firstly, the theme of passion and repression is central to the play. Alan’s fascination with horses becomes a spiritual and erotic fixation that he nurtures in secrecy. Shaffer’s use of religious language: “Equus” as a deity, Alan’s rituals as a form of worship, underscores the quasi-sacred nature of his passion. By blinding the horses, Alan symbolically rejects his god, creating a horrifying tableau of love twisted by repression. Shaffer’s poetic descriptions, especially Alan’s chants and hymns to Equus, echo with a fervour that contrasts sharply with the clinical detachment of Dr Dysart’s language. Dysart’s own reflections reveal his envy of Alan’s intensity; he confesses a sense of spiritual impotence in his life, yearning for a passion like Alan’s, even as he condemns it.

“Look... to go through life and call it yours - your life - you first have to get your own pain. Pain that's unique to you. You can't just dip into the common bin and say 'That's enough!'...”

- Equus by Peter Shaffer

The theme of identity and self-discovery also permeates the narrative. Alan’s struggle is emblematic of adolescent yearning, intensified by the constraints of his parents’ conflicting beliefs. Shaffer uses language as a way to differentiate Alan’s authentic self from the constructed identity imposed by his parents. Frank’s terse, dismissive phrases contrast with Dora’s elevated, moralistic language, reflecting the tension between secular and religious ideals that shape Alan’s psyche. Alan’s chants, spoken in an almost primal language, become a release from these imposed identities, as he seeks self-definition in his communion with Equus. Dysart’s questioning further reveals this theme, as he encourages Alan to articulate his beliefs, which in turn forces Dysart to re-evaluate his own identity.

He can hardly read. He knows no physics or engineering to make to world real for him. No paintings to show him how others have enjoyed it. No music except television jingles. No history except tales from a desperate mother. No friends. Not one kid to give him a joke, or make him know himself more moderately. He's a modern citizen for whom society doesn't exist

- Equus by Peter Shaffer

Lastly, conformity and the nature of “sanity” present a paradox. Shaffer’s dialogue reveals Dysart’s awareness of the “normalisation” process inherent in psychiatry. Dysart confesses to feeling like a “priest” performing a ritual to exorcise individuality, casting his profession in a sinister light. Shaffer’s juxtaposition of medical language with spiritual motifs suggests a critique of societal norms, where individuality and passion are sacrificed for the comfort of social acceptance. Dysart’s final monologue reveals his profound ambivalence, as he wonders whether it is worth stripping Alan of his zeal, however destructive, in favour of conventional sanity. His rhetorical questioning and use of fragmented sentences convey his internal conflict, emphasising the tragic cost of conformity.

“In an ultimate sense I cannot know what I do in this place - yet I do ultimate things. Essentially I cannot know what I do - yet I do essential things. Irreversible, terminal things. I stand in the dark with a pick in my hand, striking at heads! I need - more desperately than my children need me - a way of seeing in the dark.”

- Equus by Peter Shaffer

Why It's a Masterpiece

Equus endures as a masterpiece due to its unflinching exploration of complex psychological and societal issues. Shaffer’s play defies conventional storytelling by blending realistic psychiatry with mythic elements, creating a symbolic narrative that resonates on multiple levels. The character of Dr Dysart serves as an introspective guide, leading audiences into the depths of moral ambiguity, where the boundaries between passion, obsession, and sanity blur. His reluctance to “cure” Alan reflects Shaffer’s critique of societal norms that prioritise conformity over individual expression.

Shaffer’s innovative staging: using actors to portray horses and a minimalistic set, forces audiences to engage imaginatively with the play’s themes. This stylistic choice emphasises the raw power of Alan’s psyche and the primal nature of his worship. Equus invites viewers to consider whether the suppression of one’s innate desires is worth the stability society demands. In doing so, the play transcends time, continuing to resonate with those who question the value of “normality” and the true nature of freedom.

Conclusion

I hope you have enjoyed reading about the story of Equus by Peter Shaffer, a horrifying read for myself as a teenager - now that I'm almost 30, it doesn't become any easier. I hope that if you haven't read any Shaffer you choose to read his greatest works as soon as you can. Ah yes, he also wrote the play Amadeus - it was made into an award-winning film, (and one of my personal favourites).

Next Week: Les Enfants Terrible by Jean Cocteau

About the Creator

Annie Kapur

I am:

🙋🏽♀️ Annie

📚 Avid Reader

📝 Reviewer and Commentator

🎓 Post-Grad Millennial (M.A)

***

I have:

📖 280K+ reads on Vocal

🫶🏼 Love for reading & research

🦋/X @AnnieWithBooks

***

🏡 UK

Comments (1)

We performed a scene from the play when I was an undergrad, and I finally read it one long winter break. Still one of my favourites!