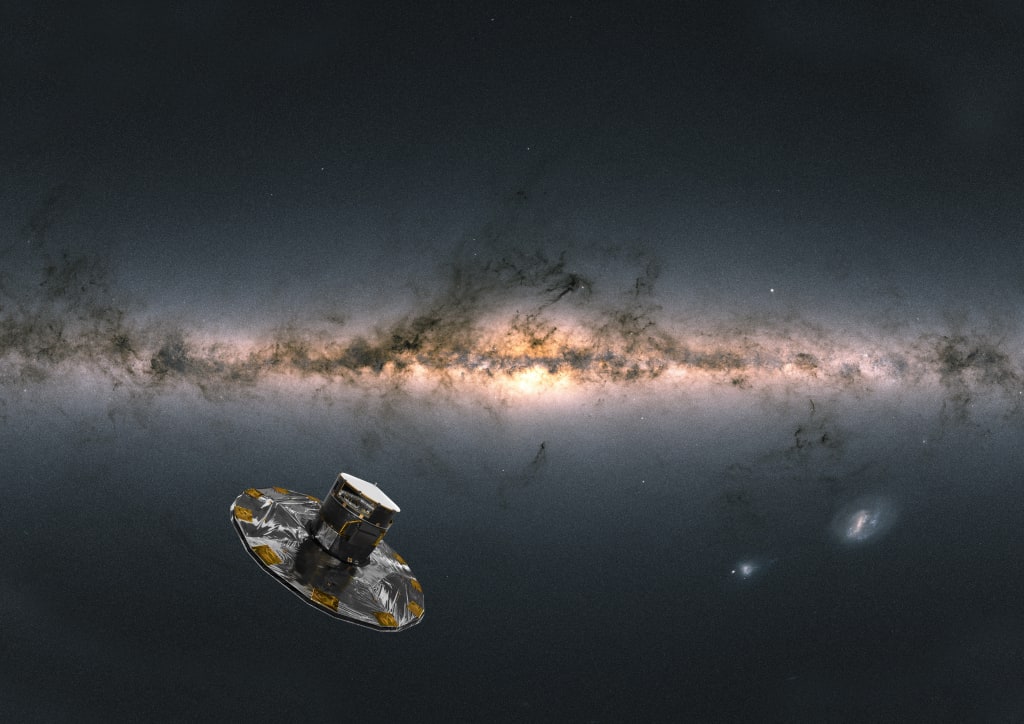

The End of an Era: Gaia’s Mission Comes to a Close — and Its Legacy Is Just Beginning

Space

In early 2025, the European Space Agency’s Gaia spacecraft officially ended its operational life after more than a decade of mapping the Milky Way with breathtaking precision. It’s a bittersweet milestone for astronomers worldwide: while Gaia has stopped collecting new data, the treasure trove it leaves behind will keep fueling discoveries for decades.

Launched in 2013, Gaia was designed to chart the positions, motions, and characteristics of over a billion stars in our galaxy — something no other mission had ever attempted. Over time, it exceeded every expectation, creating what scientists now call the most complete 3D atlas of the Milky Way ever produced.

The Final Chapter

The spacecraft’s end didn’t come as a surprise. After working flawlessly far beyond its planned five-year mission, Gaia finally ran out of cold gas, the fuel used to keep its orientation steady and precise. In January 2025, engineers commanded Gaia to stop its routine observations, and by March, they had carefully powered down its systems and nudged it into a stable “retirement orbit” around the Sun.

Still, as ESA mission director Timo Prusti noted, “Gaia’s operational phase may be over — but its scientific life has only just begun.”

A Decade of Stellar Achievements

Over ten years, Gaia recorded more than three trillion observations, cataloging the positions and movements of nearly two billion celestial objects — from stars and exoplanets to asteroids and distant quasars.

These aren’t just dots on a map. By combining astrometry (precise positions and motions), photometry (brightness and color), and spectroscopy (light composition), Gaia transformed our understanding of the Milky Way’s structure and history.

Before Gaia, astronomers had a rough outline of our galaxy — a disk with spiral arms and a central bulge. Now, they can see its structure in motion: ripples in the galactic disk, stellar streams from long-ago collisions, and evidence of dramatic mergers that shaped the Milky Way billions of years ago.

One of the most striking findings came in 2018, when Gaia revealed traces of a colossal ancient collision between the Milky Way and another galaxy, now called Gaia-Sausage-Enceladus. This cosmic crash left behind telltale patterns in stellar motions — like fossilized currents in space — allowing scientists to reconstruct part of our galaxy’s origin story.

The Data That Changed Everything

Gaia’s data has become a goldmine for nearly every branch of astrophysics. The mission helped:

- Identify thousands of new star clusters and moving groups in the galactic disk.

- Detect subtle wobbles in starlight that hint at undiscovered exoplanets.

- Track hundreds of thousands of asteroids, revealing tiny moons and orbital resonances.

- Map the distribution of dark matter in the Milky Way by analyzing how stars move through it.

For many researchers, Gaia’s database is now the cosmic “background grid” — the reference system upon which other missions, from Hubble to JWST, can calibrate their measurements.

Astronomer Amina Helmi once described Gaia as “a time machine for the Milky Way,” because it lets scientists trace stars backward through time, uncovering how the galaxy evolved and where its components originated.

The Legacy Continues

Even though the spacecraft’s cameras are now silent, the data will keep growing in scientific value. The next major release, Gaia Data Release 4 (DR4), expected in 2026, will include roughly 5.5 years of observations. The final DR5, planned for later this decade, will represent the complete 10.5-year dataset — an astronomical treasure chest unlike any before.

Processing this immense amount of data requires an enormous effort. ESA’s Data Processing and Analysis Consortium (DPAC), involving over 400 scientists and engineers across Europe, continues to refine the measurements, correct for instrument drift, and extract new discoveries hidden in the numbers.

In a way, Gaia’s “retirement” marks the beginning of a new phase — one where its data becomes a foundation for generations of astronomers to come.

Lessons for the Future

Technologically, Gaia broke new ground. Its ultra-precise sensors and stable orbit around the L2 Lagrange point set new standards for space-based astrometry. The mission’s success also showed how collaborative, open-data science can accelerate progress: Gaia’s public catalogs have already powered thousands of peer-reviewed papers worldwide.

Future missions — such as Nancy Grace Roman, PLATO, or Euclid — are building on Gaia’s design principles. Some of Gaia’s engineering innovations, like micro-arcsecond-level pointing stability, will directly influence how we explore exoplanets and dark energy in the coming decades.

And perhaps most importantly, Gaia demonstrated that the story of the galaxy is a living one. The Milky Way isn’t a static island of stars; it’s a dynamic, swirling ecosystem — full of movement, collisions, and rebirth.

A Cosmic Legacy

For the public, Gaia offered something poetic: the first truly dynamic portrait of our galactic home. Its maps let anyone — scientists and dreamers alike — glimpse where our Sun sits amid billions of neighbors, moving together in an intricate celestial dance.

As the spacecraft drifts silently through space, its legacy endures on Earth: in data servers, observatories, and classrooms. The mission gave us more than numbers — it gave us context. It taught us that every star has a journey, and by charting those journeys, we begin to understand our own.

So, while Gaia’s cameras may no longer scan the stars, its impact will echo through astronomy for generations. The next great discoveries in galactic science — and perhaps even the first detailed history of the Milky Way’s formation — will almost certainly trace their roots back to the faint, steady hum of Gaia’s instruments orbiting the Sun.

The telescope sleeps, but its stars keep speaking.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.