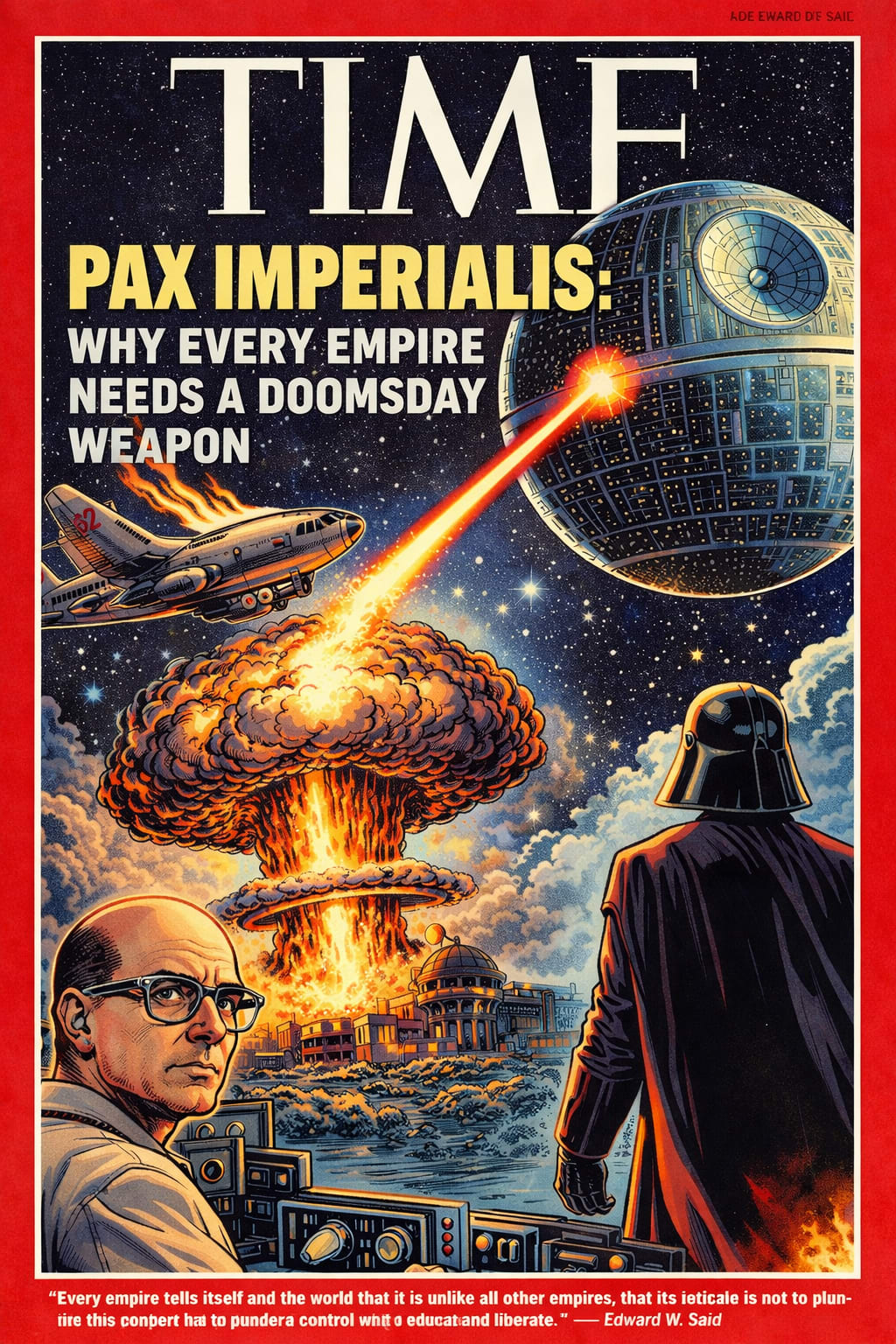

Pax Imperialis

Why Every Empire Needs a Doomsday Weapon

Every empire tells a story about itself. It claims to be a reluctant hegemon, a civilising force, a guardian of order in a chaotic world. Edward W. Said captured this imperial self-mythology with ruthless clarity when he wrote: ‘Every empire, however, tells itself and the world that it is unlike all other empires, that its mission is not to plunder and control but to educate and liberate.’ The promise is always peace, stability, progress. Yet behind this language of benevolence stands an apparatus of overwhelming violence. Empires do not rule through persuasion alone. They require an ultimate weapon, a technological embodiment of terror that transforms domination into inevitability and resistance into madness. From the atomic bomb to the Death Star, from clone armies to genetically engineered super-soldiers in The Mandalorian, the logic remains unchanged. Universal peace, or Pax, is purchased through the threat of total annihilation.

Nowhere is this imperial logic rendered more clearly in popular culture than in Rogue One: A Star Wars Story. The filmmakers explicitly grounded the Death Star narrative in the history of the Manhattan Project, turning the most iconic weapon in science fiction into a cinematic analogue of the atomic bomb. The connection was not metaphorical but structural. The production codename of Rogue One was ‘Los Alamos’, the same New Mexico town where the atomic bomb was developed. The story treatment was titled ‘Destroyer of Worlds’, the phrase J. Robert Oppenheimer famously quoted from the Bhagavad Gita after witnessing the first nuclear test: ‘Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.’ Galen Erso, the reluctant architect of the Death Star, was modelled directly on Oppenheimer, a scientist who believed he was ending a war but instead inaugurated a new age of planetary terror.

The Manhattan Project was the first true imperial superweapon programme. It was not merely a military initiative but a reorganisation of society around secrecy, compartmentalisation and technical obedience. Tens of thousands of scientists, engineers and workers were mobilised under extreme confidentiality. Many had no idea what they were building. This compartmentalisation appears almost verbatim in Rogue One and its prequel novel Catalyst. Galen Erso is kept in the dark about the weapon’s final purpose for as long as possible, allowed to believe he is working on energy research using kyber crystals, only to discover that his life’s work has been transformed into a planetary execution device. Like Oppenheimer and colleagues such as Leo Szilard, who later petitioned against the bomb’s use, Galen embodies the scientist who tries to catch the genie after releasing it. His sabotage of the reactor core is not rebellion but penance.

What unites these real and fictional histories is the doctrine of deterrence. The atomic bomb was justified as a tool to end war and preserve peace. The Death Star is justified in identical terms through the so-called Tarkin Doctrine: rule through fear of force rather than force itself. The Empire does not need to destroy every planet. It only needs to destroy one, Alderaan, publicly and without hesitation. The result is not victory but silence. Terror becomes a political technology.

This doctrine is not unique to Star Wars. It is the same imperial logic that governed Pax Romana, sustained by crucifixions along roadsides, and Pax Americana, sustained by aircraft carriers, drone fleets and nuclear submarines. Each empire speaks of stability and order while building instruments capable of erasing cities in seconds. The superweapon is not a contingency; it is the foundation of empire. Without it, the claim to universal peace collapses.

Rogue One deepens this critique by shifting the focus away from emperors and generals to engineers and technicians. The empire does not only need soldiers; it needs clerks, analysts, project managers and physicists. Power becomes bureaucratic, and atrocity becomes a spreadsheet entry. The Death Star is not built by villains in black cloaks but by people in white coats, arguing about energy yields and cooling systems. This is the true horror of empire. Its violence is rational.

The visual language of Rogue One reinforces the nuclear analogy. The firing of the Death Star superlaser mimics footage of nuclear detonations. The sudden brightness, the shockwave, the complete erasure of landscape, all echo Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The destruction of Alderaan is not simply a plot device but a cultural memory replayed in space. It asks the same question the twentieth century asked after 1945: what does power mean when it can end the world?

George Lucas conceived Star Wars in the aftermath of Vietnam, during a period when American global authority was visibly fraying. The Death Star was his cinematic condensation of Cold War anxiety, a floating doomsday machine whose existence redefined politics. With Rogue One, Lucasfilm made this connection explicit. Pablo Hidalgo of the Lucasfilm Story Group explained that Oppenheimer was a direct inspiration for Galen Erso. Director Gareth Edwards had previously worked on a BBC documentary about Hiroshima, absorbing the moral complexity of scientists who wanted to stop war but ended by changing the nature of existence itself. The empire’s ultimate weapon is not simply destructive; it is transformative. It alters the meaning of victory.

Every empire tells itself that it must build such a weapon because its enemies are uniquely dangerous. Rome spoke of barbarians, Britain of civilising savagery, the United States of freedom under threat. The Galactic Empire speaks of rebellion. The justification is always defensive, yet the outcome is always expansion. The Death Star does not merely protect the Empire; it makes resistance unthinkable. Its true function is psychological. It colonises the imagination.

This is why newer Star Wars narratives continue to reproduce the pattern. The Clone Army in the prequel trilogy is another ultimate weapon, not in a single device but in mass-produced obedience. Created in secret, justified as a necessity for peace, it becomes the instrument through which the Republic is transformed into an Empire. The clones are not merely soldiers; they are technology wearing human skin. Their existence reveals that empire does not only require machines of destruction but systems of reproduction. Violence must be scalable.

In The Mandalorian, the pattern persists with the emergence of a new race of super-fighters, enhanced through experiments with the Force. Once again, the empire, or its remnants, seeks a final solution, a biological superweapon capable of restoring universal dominance. The Force itself, once framed as spiritual and mysterious, becomes a resource to be harvested, militarised and industrialised. Peace is no longer a moral project but a technical problem.

What unites the atomic bomb, the Death Star, the clone army and the Force-enhanced soldier is their role in producing what might be called Pax Imperialis. This is not peace as reconciliation but peace as paralysis. It is a global stillness achieved not through agreement but through fear. The empire does not ask its subjects to believe in its values. It only asks them not to move.

Edward Said’s insight reveals the hypocrisy at the heart of this project. Empires do not see themselves as empires. They see themselves as exceptions. Their weapons are not instruments of domination but tools of enlightenment. The Death Star is presented as a means to end chaos. The atomic bomb was presented as a way to save lives by shortening war. The clone army was presented as a defence of democracy. Each time, the story is the same: destruction in the name of salvation.

Rogue One’s greatest achievement is to show that this story is not told only by rulers. It is internalised by those who build the weapons. Galen Erso does not see himself as an agent of tyranny. He sees himself as a scientist who made a terrible mistake. But mistakes do not float in orbit and destroy planets. Systems do. The empire does not collapse because its engineers feel regret. It collapses only when its weapon is turned against itself.

Yet even that victory is incomplete. The destruction of the Death Star in A New Hope does not end imperial logic. It merely postpones it. Another superweapon will be built, another justification will be found. The cycle continues because the empire’s core belief remains intact: that peace requires the capacity to annihilate.

In this sense, the Star Wars saga is not a fantasy of rebellion but a meditation on the persistence of imperial power. The ultimate weapon is never the final one. It is a symptom of a deeper condition: the conviction that order must be imposed from above and secured by terror. The dream of universal peace becomes inseparable from the nightmare of total destruction.

To understand this is to recognise that the Death Star is not science fiction. It is a mirror. The Manhattan Project did not end with Hiroshima. It produced a world in which annihilation is always one decision away. Rogue One simply translated that world into a galaxy far, far away. The empire did what all empires do. It told itself that it was different. It told itself that its weapon would bring peace. And in doing so, it revealed the oldest truth of power: that the promise of Pax is always written in the language of extinction.

About the Creator

Peter Ayolov

Peter Ayolov’s key contribution to media theory is the development of the "Propaganda 2.0" or the "manufacture of dissent" model, which he details in his 2024 book, The Economic Policy of Online Media: Manufacture of Dissent.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.