From Rome to Coruscant to Washington

How Republics Give Birth to Empires

George Lucas never treated Star Wars as mere fantasy. Beneath its lightsabres and starships lies a deeply historical meditation on how political systems decay. At the heart of his saga is a simple and disturbing proposition: republics are not overthrown, they are surrendered. In Lucas’s vision, the transition from freedom to tyranny is not dramatic or sudden but procedural, bureaucratic, applauded, and rationalised in the name of peace. The model for this story is not fictional at all. It is Rome.

The Roman Republic was born in 509 BCE after the last Etruscan king was expelled. It was, for its time, a remarkably sophisticated political system. Power was divided among magistrates, assemblies, and above all the Senate, which advised on law, war, finance, and religion. Initially, Rome was governed by an aristocratic elite, the patricians, but over nearly two centuries the plebeians forced their way into political life. They gained tribunes, assemblies, and finally the power to pass laws binding on all citizens. Rome appeared to embody the dream of a stable, participatory republic.

Yet the seeds of empire were embedded in the republic itself. Expansion created inequality, wealth concentrated in a few hands, armies became loyal to generals rather than to institutions, and the Senate transformed from guardian of the common good into a battlefield of factions. Reformers such as the Gracchi were murdered, conspiracies like Catiline’s shook the city, and civil wars became routine. By the first century BCE, Rome was still called a republic, but it no longer behaved like one.

Julius Caesar did not overthrow the republic by force alone. He was invited into power by a frightened elite who believed that order was more valuable than law. When he crossed the Rubicon and marched on Rome, he did not destroy the system; he revealed how hollow it had already become. After his assassination, Augustus completed the transformation. He preserved republican language, offices, and ceremonies, but emptied them of substance. The Senate survived, but as a legitimising theatre. Assemblies still met, but they no longer governed. The republic became an empire that pretended not to be one.

This is precisely the political tragedy George Lucas retells in Star Wars.

The Galactic Republic is not conquered by external enemies. It collapses from inside. It is paralysed by procedure, corporate influence, and moral exhaustion. Trade federations manipulate legislation, senators trade favours, and nobody believes in the system anymore. Into this decay steps Palpatine, a charismatic insider who does not destroy democracy but accelerates its own tendencies. Like Caesar or Augustus, he presents himself as a restorer of order. Crisis after crisis is manufactured or exploited: first trade disputes, then separatist movements, then full-scale war. Each emergency justifies more executive power.

The moment of transition is not a coup. It is a vote. The Senate applauds the end of its own authority. Padmé’s line in Revenge of the Sith is one of the most brutally honest political statements in modern cinema: ‘So this is how liberty dies… with thunderous applause.’ That applause echoes across two thousand years of history, from Rome to Weimar Germany to Washington.

Lucas made the Empire deliberately resemble twentieth-century fascism. Imperial uniforms echo those of Nazi Germany. Stormtroopers borrow their name from German paramilitaries. The architecture is monumental, cold, and dehumanising. Yet Lucas’s most unsettling claim is not about dictators. It is about citizens. The people cheer because they are tired. They exchange freedom for the promise of security, and they do so willingly.

The Roman emperors perfected this formula. Augustus ruled not as a tyrant but as a saviour. He claimed to have ended civil war, restored peace, and returned dignity to Rome. His successors expanded the empire across Europe, North Africa, and the Near East. Wealth poured into the capital, roads connected the provinces, and the idea of Pax Romana was born: peace through domination. But this peace depended on a vast military machine, on taxation, on surveillance, and on the constant threat of annihilation. Rebellions were crushed, cities destroyed, and enemies displayed as examples. Rome’s peace was real, but it was built on terror.

Lucas translates Pax Romana into Pax Galactica.

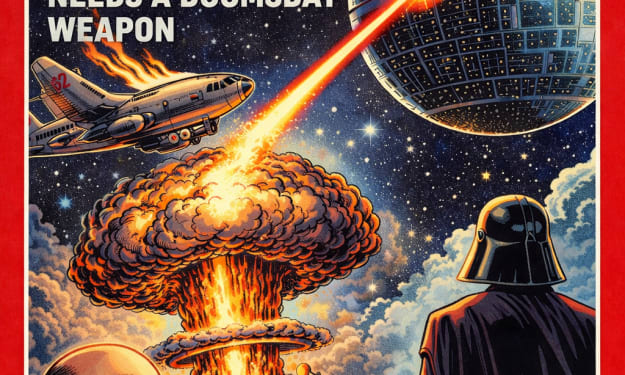

The Death Star is not simply a weapon; it is a political concept. It embodies the idea that universal peace requires absolute power. Its destruction of Alderaan is the Star Wars equivalent of Rome’s destruction of Carthage, or the nuclear annihilation of Hiroshima. It is not strategic. It is symbolic. It is the declaration that resistance is futile because existence itself can be erased.

Lucas conceived Star Wars during the Vietnam War and the Nixon era, and he has openly stated that he identified the Empire with the United States of that time. The Rebels were not glamorous freedom fighters; they were guerrillas, a small and desperate force confronting a technologically superior power. This inversion unsettled American audiences. The Empire was not foreign. It was familiar.

The Roman parallel deepens this unease. Rome did not fall because of invasion alone. It fell because the cost of empire became unsustainable. Expansion required constant military spending, endless administration, and increasingly desperate reforms. Diocletian split the empire in two to make it manageable, just as modern states decentralise power while claiming to preserve unity. Yet division only delayed collapse. In 476 CE the Western Empire ended, while the Eastern Empire survived another thousand years, ruling from Constantinople until 1453. Empire, once born, does not die quickly. It mutates.

Lucas suggests the same about his galaxy. The fall of the Emperor does not end imperial logic. Another superweapon will be built, another crisis will be staged, another saviour will emerge. The republic is restored, but the audience already knows the pattern. Without vigilance, the cycle will repeat.

The United States looms behind all of this. Lucas does not say that America is Rome, but he asks what happens when a republic becomes convinced that it is indispensable. Like Rome, the United States emerged from rebellion, celebrated liberty, and built a constitutional order. Like Rome, it expanded, militarised, and gradually normalised emergency powers. Like Rome, it tells itself that it is different, that its mission is not domination but liberation.

Edward Said once wrote that every empire insists that it is unlike all others, that it does not rule but educates, not controls but frees. Rome said this. Britain said this. The United States says this. The Galactic Empire says this too. The story is always the same. The audience is invited to believe that the system exists for its own good, until one day the applause fades and the machinery is revealed.

George Lucas did not merely create a saga about good and evil. He created a warning about political memory. Republics do not become empires because villains seize them. They become empires because citizens forget what they were built to resist.

And perhaps it is no coincidence that his closest friend and collaborator, Francis Ford Coppola, has now made his latest film presenting New York as a falling Rome, a metropolis where decadence, spectacle, and institutional exhaustion announce not renewal but decline, as if the final act of Lucas’s parable has returned home to its real imperial capital.

About the Creator

Peter Ayolov

Peter Ayolov’s key contribution to media theory is the development of the "Propaganda 2.0" or the "manufacture of dissent" model, which he details in his 2024 book, The Economic Policy of Online Media: Manufacture of Dissent.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.