During Earth's previous global warming episodes, little marine animals have invariably become extinct.

Ocean life is once again in danger due to carbon levels.

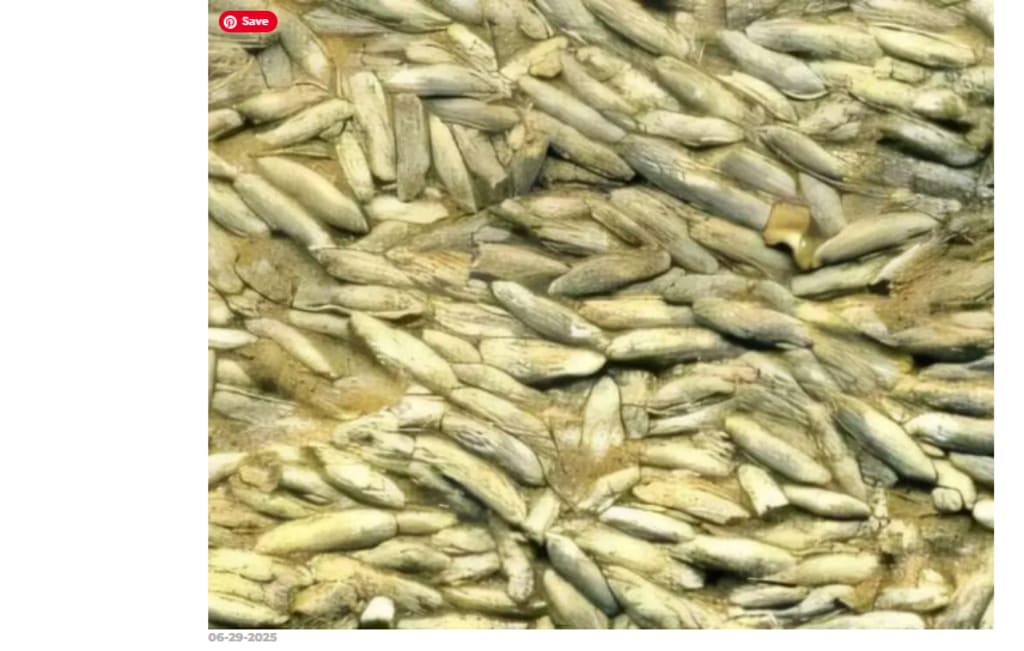

Fusulines, which are shells tiny than a grain of sand, are some of the greatest pages in the extensive, detailed records of climate change kept by Earth's oceans.

According to a new study, these microscopic record-keepers thrived when the world cooled and almost disappeared twice when volcanic activity caused global temperatures to rise.

Professor Shuzhong Shen of Nanjing University oversaw the project. To create an exceptionally detailed image of ancient marine life, the study team pieced together 1,391 fossil species and 299 rock pieces.

Carbon changes were recorded using fusulines.

Foraminifera, single-celled protists that form carbonate shells, are the study's main stars. From 344 million to 252 million years ago, the seafloor was covered by one order, Fusulinida, which acted as "carbonate rock factories," spewing forth enormous reefs as they developed.

According to Shen's research, there were two periods of diversification: one at the start of the Permian and another during the late Carboniferous cooling.

The second wave favoured larger forms with honeycomb-like walls that probably housed photosynthetic partners, while the first wave produced small, basic shells.

Warm spikes decreased fusulines.

Sea levels decreased, new shallow habitats emerged, and glaciers froze up water as the climate cooled. During the 40 million-year chill, the number of fusuline species tripled, which is similar to what happened to later planktonic cousins during the Cenozoic cooling trend.

The story of warm pulses was different. About 45% of fusuline species were exterminated in less than a million years due to the Kasimovian warming that occurred approximately 304 million years ago. The curve then fell once again as temperatures increased between 294 and 284 million years ago.

Their destiny was sealed by the end-Permian supervolcano. In a window of time shorter than the current human generation, 59.5 percent of the remaining species vanished during that episode.

Extinction was caused by carbon from volcanoes.

According to Shen's timeline, a pulse of basalt from massive volcanic areas like Siberia and Emeishan coincides with each extinction surge.

Benthic creatures were unable to avoid the triple punch caused by those eruptions, which pumped carbon dioxide quickly enough to warm surface waters by 5 to 10 °F, acidify saltwater, and deplete it of oxygen.

According to carbon isotope data, the waters became more acidic anytime the ratio of 87Sr to 86Sr decreased, which is a sign of the weathering of fresh volcanic materials.

Simultaneously, modelled oxygen levels fell below the critical threshold for supporting significant seabed life, which is consistent with current evidence that foraminiferal variety drastically decreases in low-oxygen zones.

The orbital cycles were less important.

Shen's team discovered faint but persistent Milankovitch cycles, which are large wobbles in Earth's orbit that last between two and one million years, in addition to the spectacular crashes.

Gentler seasons might have encouraged glacier expansion and nutrient runoff during those cycles' minimum, pushing speciation upward.

Although the cycles only account for 10% of the diversity curve, their fingerprint is sufficiently distinct to remind us that life is modulated by even tiny orbital nudges.

However, quick volcanic occurrences coincide with the sharpest increases and falls, indicating that the primary pace was dictated by climate severity rather than orbital pacing.

Ocean life is once again in danger due to carbon levels.

Professor Shen underlined that "protecting ecosystems and mitigating climate change are urgent tasks of our time." The most depressing paragraph of the report contrasts the rates of warming in the past with those in the present.

Modern reef-building calcifiers already exhibit stress in warmer, more acidic waters, and the rate of human-induced warming is at least ten times higher than the rate that wiped out fusulines.

Long-term greenhouse gas emissions may drive today's carbonate shell builders, corals, coccolithophores, and huge benthic foraminifera towards the same cliff if the past is any indication.

Cycles of extinction linked to carbon

The team fed each first-and last-appearance datum into a limited optimisation technique called CONOP to achieve sub-45,000-year resolution.

Supercomputers converted disparate field data into a single high-definition timeline by iterating millions of potential stratigraphic orders until the best fit was found.

Three distinct resample sizes replicated the identical peaks and troughs, demonstrating that sampling gaps do not distort the pattern, according to rarefaction testing.

The shorter cycles that suggest orbital pacing were identified by the researchers by excluding patterns that were longer than 10 million years.

Fusulines' ascent and decline

After that, the specialists performed multivariate regressions against seven environmental proxies, ranging from sea-level curves to carbon isotopes.

There is little question that the physical environment established the rules of life and death for fusulines, as the best model explains 81% of the variety swings by combining carbon dioxide, seawater strontium, oxygen availability, and carbon isotopes.

The Fusulines disappeared, but their tale endures. They highlight how chilly periods can foster accelerated innovation and demonstrate how even strong, dominant lineages can be silenced by fast warming.

Today's marine ecosystems are at a similar crossroads, with greenhouse gases rising and exhaust pipes and smokestacks taking the role of volcanic analogues.

Although the fossil record provides a stark warning, it does not reassure us that life can adapt at the rate we are pressing it to.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.