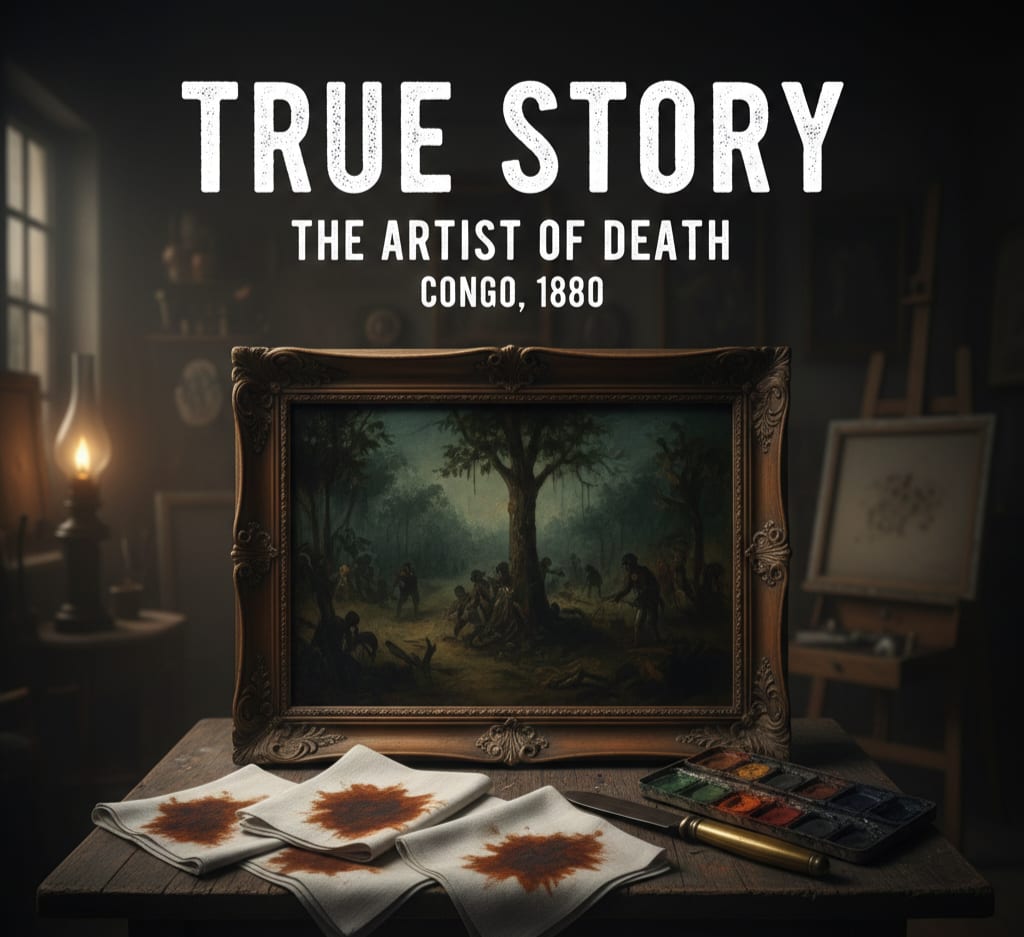

The Brush of Death: The Haunting Tale of James Jameson and the Six-Handkerchief Girl.

How the heir to a global whiskey empire turned cannibalistic rituals into watercolors in the heart of the Congo.

We often believe that human evil has a limit, a floor beyond which no one can sink. But history, in its darkest corners, proves us wrong. The story of James S. Jameson, heir to the famous Irish whiskey dynasty, is a descent into a madness so profound it defies words

Introduction: When Evil Knows No Bounds

For those who immerse themselves in the annals of true crime and historical atrocities, there often comes a feeling of desensitization. We tend to believe we have seen the worst of human nature—the serial killers, the tyrants, and the madmen. However, history occasionally reveals a "basement" of human depravity that we never knew existed. The story of James Sligo Jameson is not that of a common criminal from the fringes of society; it is the story of a man from the pinnacle of the British aristocratic elite. The heir to the world-renowned Jameson Irish Whiskey empire, he was a man who turned the agony of a child into a "work of art."

Historical Context: Into the Heart of Darkness

In 1887, Jameson joined one of the most famous and controversial expeditions of the 19th century: the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition. Led by the legendary—and often brutal—explorer Henry Morton Stanley, the mission's public goal was to rescue the besieged governor of Equatoria. Yet, beneath this humanitarian veneer lay a world of colonial greed and darkness. Accompanying the mission was a Syrian translator named Assad Farran, whose eventual testimony would shock the Victorian world by revealing the horrors hidden within the Congo’s dense rainforests.

A Diabolical Curiosity: The Cheapest Bargain in History

Jameson was not driven by the thrill of discovery or the nobility of the rescue mission. Instead, he possessed a morbid, voyeuristic obsession: he wanted to witness cannibalism with his own eyes. As a self-proclaimed naturalist and artist, he didn't just want to hear the legends; he wanted to document the act through his sketches and watercolors.

In a moment where humanity completely evaporated, Jameson approached the notorious slave trader Tippu Tib in the town of Ribakiba. With chilling composure, he asked if he could witness a cannibalistic feast. In a time and place where the lives of the indigenous people were treated as disposable, Jameson struck the most horrific bargain in the history of exploration. He purchased a ten-year-old African girl. The price? Six cotton handkerchiefs. Six pieces of cloth were all it took for this aristocrat to buy a human life for the sake of a "scientific experiment."

The Macabre Scene: A Brush Painting the Bleeding

Jameson took the terrified child to a hut belonging to a local tribe. Through the translator, Assad Farran, he delivered a message that remains etched in the halls of infamy: "This girl is a gift from the white man; he wishes to see her eaten."

What followed defies the capacity of the human mind to comprehend. The men tied the child to a tree. In those final moments, the girl reportedly looked toward Jameson—the well-dressed white man—with eyes pleading for mercy, perhaps believing in her innocence that he would intervene. He did not. Instead, he opened his sketchbook, prepared his watercolors, and sharpened his pencils.

The tribesmen began to disembowel the girl while she was still alive. Her screams, which echoed through the jungle, did not move a single muscle in Jameson's body. He watched the flow of blood and the rhythmic tremors of her small frame, meticulously transferring every detail to his paper. He sketched her as she was slaughtered, he sketched her as she was butchered into pieces, and he sketched the preparations for the feast. By the end of the session, Jameson had completed six detailed watercolors, each documenting a different stage of a human being's destruction.

The Scandal and the End of a Monster

The truth did not emerge until after Jameson died of a fever in August 1888. Following his death, his diaries and the haunting testimony of Assad Farran reached the British press. The public in London was paralyzed by the revelation; the perpetrator was not a "savage" from the jungle, but a scion of one of their most prestigious families.

The colonial authorities, including Henry Morton Stanley, scrambled to distance themselves. Assad Farran was pressured to retract his story and was accused of perjury and treason against the British Empire. However, Jameson's own diaries and the existence of the sketches served as silent, undeniable witnesses. Jameson had admitted to the event in his writings, though he attempted to dismiss it as a "joke" or a "mistake," claiming he didn't think the tribesmen would actually go through with it—a hollow excuse that crumbled against the fact that he sat through the entire process to finish six separate paintings.

Conclusion: The Cold Lessons of History

James Sligo Jameson died at the age of 32, leaving behind a stain of shame that his family’s wealth could never wash away. His story remains a harrowing testament to the ultimate peak of colonial arrogance, where human beings were reduced to mere "subjects" for a canvas.

The story of "The Artist of Death" serves as a reminder that civilization, wealth, and fine clothing can mask a ferocity that far exceeds that of any wild animal. It leaves us with a bitter question: How many more lives were extinguished in the "Heart of Darkness" without a witness like Assad Farran? And how many monsters have lived and died wearing the mask of "Great Explorers"?

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.