Performance in the African Oral Literature

Arts and Nature

PERFORMANCE IN THE AFRICAN ORAL LITERATURE

BY SANUSI CAMARA, AN AWARD-WINNING AUTHOR

Especially in Africa, performance occupies a central role in the oral literature. Tala describes the performance as the representation of an oral script, reading of a poem, the performance of a ditty or narration of occasional tales. Largely, African literature was in the form of words which were consumed through interaction in artful performances as one of the aesthetic symbols of the culture. It is apparent that, in its specific context, oral literature in Africa has not always followed the Western formula, which has always resulted in the misunderstanding of the verbal arts by Western scholars. However, performance in African oral literature is essential as it has been the act of passing down cultures, adding more meanings to speeches, and fostering societal cohesion.

There is a good quantity of culture that is being passed down orally which is better understood through performances. Many poets and artists have shown why it is important to look into those performances as interpretations of their culture in a heterogeneous continent like Africa. Oral literature, which is sometimes esoteric, is differently given informed meanings by different audiences as what may mean this way may mean differently to others. There seems to be a conclusive consensus attached to the meanings of verbal acts when plotted in situational performances, however. Since the oral literature of Africa is mostly preliterate, performances tend to revive the culture that otherwise would have been lost. Oral texts of spoken-word poets and musicians cannot usually arouse feelings and understanding if not accompanied by performance during their rendition. Though it draws attention to what is being said, it goes alongside its technicalities and difficulties.

Aside from passing down cultures in their actual context, the performance also gives soul to the dead oral text. Spoken-word poets and artists have a great advantage in using a variety of tools available to communicate the oral text more stylistically and visually. The heterogeneous Africa has varieties of tones that can, however, communicate verbs rather differently; but these different tones have a direct connection to the perceived cultural traits of the individual tribes. Other structural elements of performance, other than tone, are musical instruments and the display of those musical instruments on special occasions. For example, hymns sung at traditional ‘gamos’ and coded ditties sung at ritual events such as boys’ and girls’ circumcisions, having special emphasis on certain syllables, do effectively communicate messages about the cultures. These hymns and songs are made lively by a special type of drum called ‘tamalaa’ and other traditional drums, respectively. The performers, in this respect, employ visual representation of these words in verbal acts. Most of these songs and hymns are supplemented by chorale and very few soloists do this independent of their audience. Often, correct and direct meanings cannot always be established about these songs by none other than those who have the moral autonomy to put them into visual acts. The performances of these performers would not make sense without the chorus from the audience, thus, the acts are done by both the artists and the onlookers.

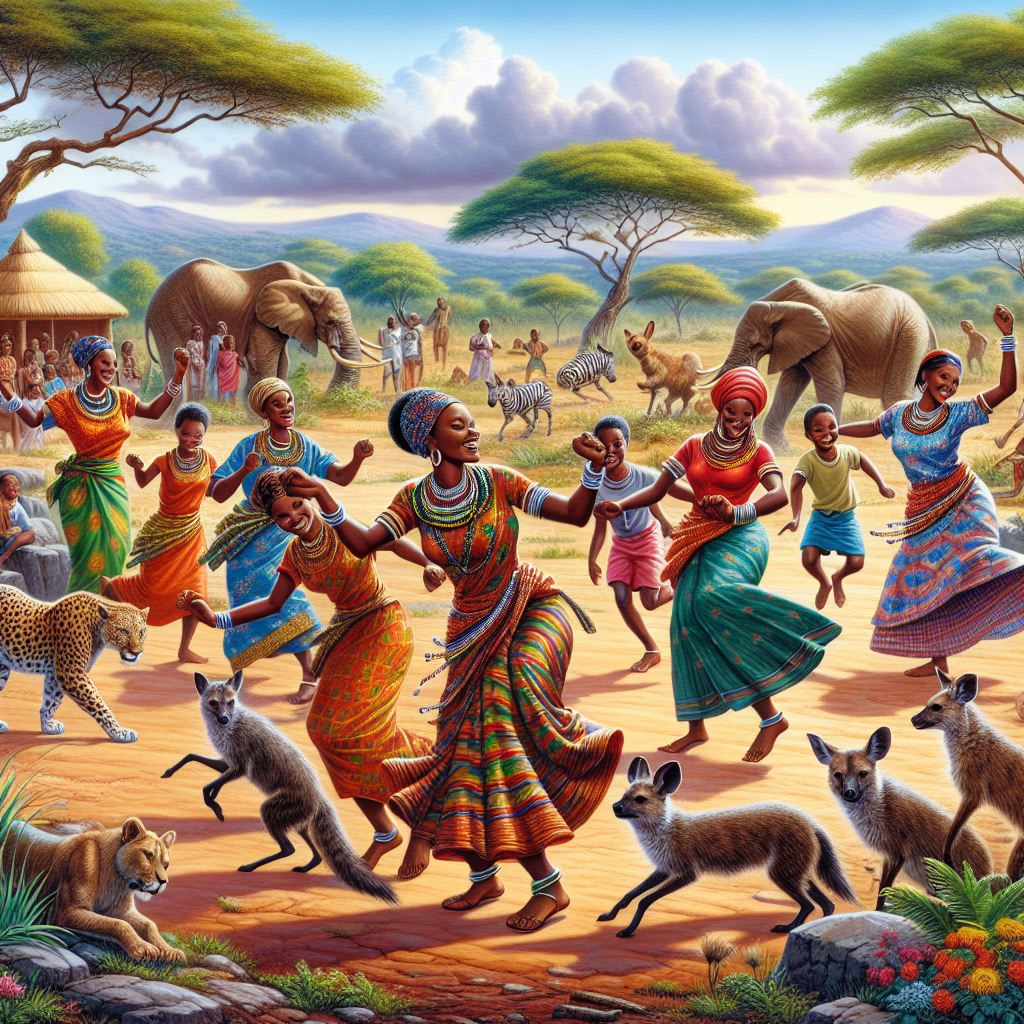

Traditional storytelling, for instance, has a great potential to foster societal cohesion where several children sit around the burning flame of the evening fire to listen to an expert who would narrate tales, creating mental images of wild animals such as dragons, elephants, lions, and so on. These animals may not be natives in a particular geographic territory but through traditional tales, children often have a way of visualizing their sizes, fierceness, and time-space. Such performances of oral literature teach children about the symbiosis that exists among animals, as well as, between these animals and humans. Most Gambian tales that centre around stories that feature ‘suluu ning sang’ (hyena and hare) often create atmospheres that explicitly lay out consequences of wiseness on the part of the hare who always makes good decisions, and foolishness on the part of the hyena who often makes bad decisions. Children, in reminiscence of bad consequences and good consequences that happen to the hyena and hare, often try to mimic the hare to benefit from similar rewards. These stories may make the combination of words, gestures, and dance from plot to plot. They can also create peace of mind as children no longer bother themselves with stressful work they probably had in the previous day. However, it can also create incurable nostalgia in elders who have passed the age of listening to late-evening storytelling, or who seem too busy to narrate such stories to children.

Sadly, oral literature and its performances have received criticisms from the western scholars about its lack of following a set of genres and rules. Abdullahi Kadir Ayinde, (PhD) of the Department of English at the Yobe State University, notes, “[The] Eurocentric’s definitions, thus, limit the term literature to only the written texts to the exclusion of all unwritten art forms.” Susan N. Kiguli, in her article, agrees with Olabiyi Babalola saying, “In the domain, standard practice by African and non-African students of African oral works of literature is to posit a tabula rasa. Since African cultures are reputedly ‘preliterate’, it is assumed that they thereby lack a tradition of literary criticism, the latter being it is largely and strongly believed—an attribute of literate cultures.” Unfortunately, African oral literature intellectuals have used theories, genres, and rules that are made up of the West and have shown signs of the loss of oral literature in Africa sooner or later.

REFERENCES:

Abdullahi Kadir Ayinde, ASPECTS OF AFRICAN ORAL LITERATURE AND PERFORMANCE AESTHETICS. Yobe State University, PMB 114, Damaturu

Finnegan, R. 2012. 1. The ‘Oral’ Nature of African Unwritten Literature. In Oral Literature in Africa. Open Book Publishers. Retrieved from http://books.openedition.org/obp/1187

Kiguli, Susan N., Performer-critics in oral performance in African societies, Kunapipi, 34(1), 2012. Available at: https://ro.uo./kunapipi/vol34/iss1/15

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.