Aesthetics

Before fitness YouTubers

Human capacity for interpretation and understanding of the world is complex and moves precariously in balance between the objective and the subjective. Beauty itself might not be fully objective, but it often is (either as perceived, e.g. symmetry; or shared, e.g. trend). And it drives us: beauty gives us pleasure.

While the objectivity of beauty can be derived by what the majority of people in the world think as beautiful, and therefore self-reported, once we establish that some things are ‘beauty’, then we can see, via neurobiology, how certain areas of the brain light up (activate). Beauty leads to pleasure, and to a sense of reward.

But can neuroscience already tell us WHAT is beauty? Nope.

It can tell us that looking at Henry Cavill taking a bath as the Witcher, and listening to Lana del Rey, Mozart, or Whitney Houston are considered beautiful to our brain — much like a beautiful landscape — but it cannot tell us what ‘beauty’ is. What is the essence shared across fields and perceptions that holds the key to the significance of this inescapable concept.

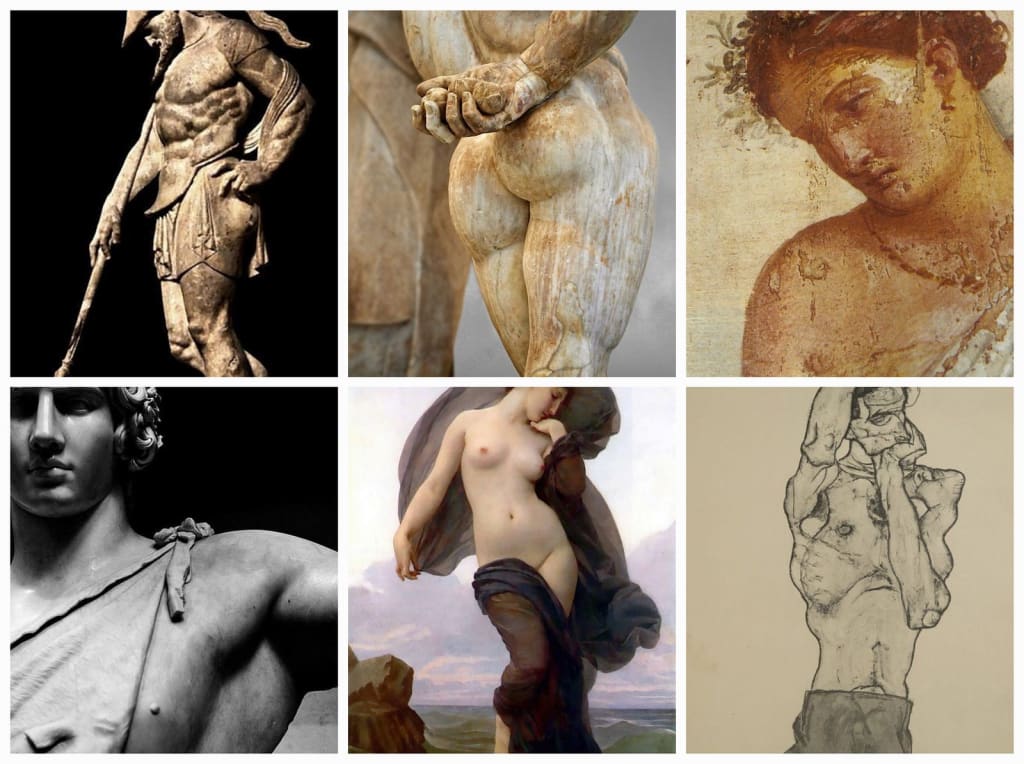

Through the body we perceive beauty, and through beauty we perceive the body. With art, the body becomes a demigod, withstanding time and outliving subject and artist. As Ali Smith would put it, art can make the body ‘float’.

When it comes to the ancients, we mostly see the Greeks naked. Especially men. Specifically, we see workers working naked, warriors battling with nothing but their swords to adorn and protect them, and athletes in the nude. But was it like this in life? Not always, as Sarah Murray writes in Aeon, but there were spaces where it was normalised or appropriate. There were different types of nudity too: from the unaroused athletes and warriors to dirty pictures of sex scenes or well-endowed satyrs.

The naked male form held profound significance within ancient Greek culture, embodying a multitude of nuanced symbols. It served as a potent emblem, reflecting various aspects of Greek ideals and values. Central to this symbolism was the phallus, which stood not only as a representation of physical prowess but also as a potent symbol of authority and intimidation.

The nude male body, celebrated in Greek art and literature, conveyed notions of strength, beauty, and athleticism. It epitomized the idealized form of the Greek male, representing the pursuit of perfection in both physique and character. Through sculptures like the iconic statues of athletes or gods, such as the renowned Discobolus or the statue of Hermes, the Greeks immortalized the human form as an epitome of aesthetic excellence and divine grace.

When we talk about real-life Greek nudity, this had many roles, as well as that of a ‘costume’ that helped differentiate the elite Greeks from the lower barbarians, and of religious rituals. But male nudity was extremely prominent in athleticism (civic nudity) where athletes were expected to both train and compete naked. Nudity in athletes, and their artistic representations, also served to create erotic situations. Often, for more mature man to seduce or groom younger athletes.

In ancient Greek and Roman societies, physical fitness was regarded as a core virtue closely tied to moral and intellectual excellence. The ideal man was seen as having both a strong body and a strong mind, captured in the Roman phrase mens sana in corpore sano. In Greece, especially, physical beauty and fitness were associated with virtue and intelligence, expressed in the concept of kalos kai agathos. Philosophers such as Aristotle and Xenophon promoted a holistic view of life, rejecting a separation between mind and body and valuing physical activity as essential to personal and moral development.

Sparta exemplified this ideal in an extreme form: men were trained as warriors and women as mothers of warriors, with both expected to maintain physical fitness. Those deemed unfit—particularly male infants—could be killed. The Romans later adopted and adapted Greek ideals, emphasizing balance between physical health and moral character. Over time, these ideas shaped a lasting belief in the interconnected importance of physical and mental well-being.

Exercise has long been understood as medicine. While Hippocrates and Galen promoted physical activity for health in Greece and Rome, the earliest known physician to formally prescribe exercise was Susruta in 6th-century BCE India. He advocated daily, moderate exercise tailored to age, strength, terrain, and diet, arguing it strengthened the body, improved digestion and appearance, and slowed ageing. Around the same time, artists such as Polyclitus sought to define the ideal body through mathematical proportion, shaping Western ideas of beauty as balance and harmony.

Yet the human body in art has never been neutral. Portraits and nudes carry stories of class, morality, and power. Historically, women’s bodies were depicted less for strength or athleticism and more for sexual, moral, or anatomical purposes—often framed through the male gaze. As John Berger noted, women were frequently portrayed as complicit objects of visual pleasure, even when morally condemned for it.

When women artists began reclaiming the nude in the 20th century, the reaction was often hostile. Their work was dismissed as vulgar or accused of reinforcing objectification, revealing deep discomfort with women controlling their own representation. Artists like Jenny Saville exposed the violence behind society’s obsession with “fixing” women’s bodies, highlighting how physical appearance is treated as a problem to be cured.

Representations of bodies outside the ideal—particularly fat bodies—further reveal social prejudice. Artists such as Fernando Botero and Lucian Freud challenge viewers by depicting volume, flesh, and rest, yet reactions remain conflicted, oscillating between fascination, discomfort, and judgment. The question persists: are these images acts of empathy, critique, or voyeurism?

By the 1960s and 70s, this tension reached a turning point as artists began using their own bodies as the artwork. Performance art collapsed the distance between representation and reality, allowing artists—especially women and gender-nonconforming individuals—to reclaim bodily autonomy and confront cultural norms directly. The body was no longer just depicted; it became the site of meaning itself.

The portrayal of ideal bodies — fit, male (though there is an ideal for female bodies as well), and, perplexingly, white bodies — poses a significant challenge to achieving various pursuits, including racial equality. Take, for example, the depiction of Jesus as white, a figure among many who have been inaccurately portrayed throughout art, history books, and broader cultural narratives.

However, the issue extends beyond skin colour. The pervasive idealization of body types is more pronounced than ever. While some may argue that not all media representations qualify as ‘art’, they undeniably contribute to a cultural tradition that across time views bodies through the lenses of artifacts, art, and now contemporary media. Moreover, the emphasis on body fitness often disregards the diverse array of body types, perpetuating a narrow and exclusive standard of beauty and health. This standard may not be attainable or sustainable for everyone, further complicating efforts towards inclusive representation and genuine equality. Good thing that I am beautiful, even if Avocado shaped may not be everyone’s cup of…guacamole.

Exploring the ideological connections spanning antiquity to modernity, through contemporary media and art, and focusing on the body and fitness, I simply hope to lower my cholesterol levels.

Now, while this may sound too cringey, cheesy, or cliché: Stay healthy, embrace yourself. Engage in sports — not for achieving ideal bodies, but because they’re incredibly enjoyable and beneficial. We’re still nature’s own work of art.

About the Creator

Avocado Nunzella BSc (Psych) -- M.A.P

Asterion, Jess, Avo, and all the other ghosts.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.