Samurai's Dream

Noble Death in a Decaying Empire

"How fate smiles on me. As a samurai in this era of peace I have been wishing for a noble death. Now fate has called me here. " - Shinzaemon Shimada, 13 Assassins

In 13 Assassins (2010), directed by Takashi Miike, the samurai film becomes something more than a genre exercise. It becomes an elegy, a political parable, and a meditation on the strange psychology of men who live in order to die well. Set in 1844, in the waning years of the Edo period, the film unfolds against the quiet rot of the Tokugawa shogunate. Peace has endured too long. The sword has lost its field. Honour has become ceremonial. And power, insulated from consequence, has curdled into cruelty.

Lord Matsudaira Naritsugu of Akashi embodies that corruption. Protected by the Shōgun, who is also his half-brother, Naritsugu rapes, mutilates and murders with impunity. His sadism is not impulsive; it is aristocratic. He destroys families for sport. He butchers loyalty. He cuts down peasants and nobles alike because he can. When he is slated to ascend to the Shogunate Council, the danger ceases to be personal and becomes systemic. His cruelty, given institutional authority, will ignite civil war. The realm stands on the brink not because enemies gather at the border, but because madness sits within the palace.

The protest of the Mamiya clan’s lord—who commits seppuku after Naritsugu murders his entire family—does not awaken justice. It exposes its absence. The Shōgun refuses to punish his brother. The state closes ranks around blood. At this point, Sir Doi Toshitsura, the Justice Minister, recognises that legality has failed. Law has become the shield of barbarism. And so he turns to something older than law: the sword.

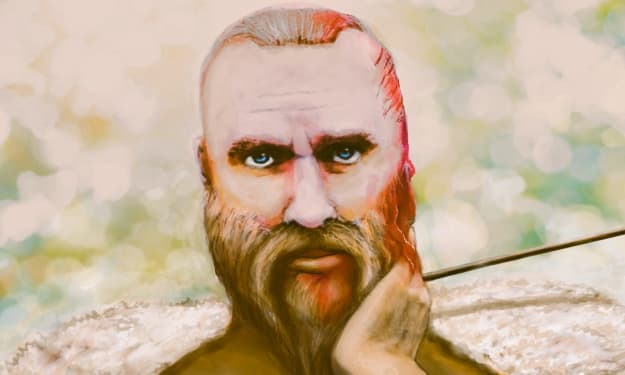

Enter Shimada Shinzaemon, portrayed with stoic depth by Kōji Yakusho. He is first glimpsed fishing, balanced on a ladder over calm water. It is an image of tranquillity, almost comic in its pastoral simplicity. Yet beneath the surface lies frustration. Shinzaemon is a warrior born into an age of peace. The Tokugawa order has stabilised the country so effectively that men trained for battle now find themselves unemployed by history. For such men, existence becomes suspended. They wait for a worthy death that never arrives.

When Sir Doi presents the mutilated woman—her limbs severed, her tongue cut out—Shinzaemon confronts the flesh of tyranny. Asked about her family, the woman takes a brush in her mouth and writes two words: TOTAL MASSACRE. It is one of the film’s most devastating moments. Language returns where speech has been destroyed. Writing replaces the tongue. The brush becomes testimony.

And then Shinzaemon smiles.

The smile shocks Sir Doi and the audience alike. But it is not the smile of cruelty. It is the smile of recognition. Fate, long silent, has finally spoken. In that instant he utters the line that defines the film’s spiritual core: “How fate smiles on me. As a samurai in this era of peace I have been wishing for a noble death. Now fate has called me here.”

This is the paradox of the samurai ethic. Life is not the highest good; honour is. Existence without meaningful risk is a kind of half-life. To modern ears, this sounds pathological. What kind of culture teaches young men to aspire to glorious extinction? Yet for Shinzaemon, the mission offers coherence. It restores the unity between skill and purpose. The “warrior’s battle shakes” he reveals—his trembling hands—are not fear but anticipation. At last, his training will not decay unused.

The plan is simple and suicidal. Gather a band of loyal assassins. Ambush Naritsugu during his journey. Kill him, even if it costs every life involved. Then, if by some miracle anyone survives, they must commit seppuku for daring to spill the blood of a Shōgun’s brother. It is an ultimate task: murder in the name of order, followed by self-execution in the name of loyalty.

Shinzaemon assembles eleven men, remnants of a fading class. In an era where the samurai spirit has thinned, finding true warriors is difficult. They are joined unexpectedly by Koyata, a wild, irreverent young hunter who mocks samurai rigidity yet insists on accompanying them. His presence injects tension. He represents something new—irreverent, flexible, unbound by strict codes. The old and the emergent Japan walk together into battle.

The ambush is prepared with ingenuity. The village is transformed into a death trap. Expectations are calculated: seventy guards. Manageable odds for men prepared to die. But Naritsugu’s entourage swells to two hundred. The arithmetic becomes absurd. Yet this does not break them. If anything, it clarifies the outcome. They were never fighting to survive. They were fighting to justify their deaths.

What follows is a forty-five-minute battle sequence that is less spectacle than ordeal. Arrows rain, swords flash, bodies fall in mud and blood. Unlike the stylised exuberance of many action films, this combat is grounded, brutal and exhausting. The warriors do not leap impossibly across rooftops; they stumble, bleed, strain. Death comes repeatedly and intimately. Ten of the thirteen assassins perish. Some fight until their bodies collapse beneath accumulated wounds. The choreography conveys not triumph but attrition.

Yet beneath the carnage lies a quiet lament. This is not simply the elimination of a tyrant. It is the self-immolation of a class. The samurai prove their worth precisely by annihilating themselves. Their victory is inseparable from their extinction.

In the final confrontation, Shinzaemon faces Naritsugu and his loyal retainer Hanbei. The duel between Shinzaemon and Hanbei crystallises a deeper conflict: loyalty to a master versus loyalty to the realm. Hanbei insists that a samurai exists to serve his lord unconditionally. Shinzaemon counters that lords cannot survive without the people. If a lord abuses power, rebellion becomes inevitable. Authority is not metaphysical; it is reciprocal.

After blinding Hanbei with mud—a pragmatic, almost dishonourable move—Shinzaemon decapitates him. Honour, here, bends to necessity. There is no pristine duel in open field. There is mud, desperation and survival. Naritsugu watches his retainer’s head fall and kicks it aside. Even now he cannot comprehend the gravity of his position. He proclaims that people and samurai exist solely to serve their lords. Shinzaemon replies that without the people, there are no lords.

When they clash, both are mortally wounded. Naritsugu, crawling in fear and mud, weeps and thanks Shinzaemon for giving him the most exciting day of his life. It is a chilling confession. For Naritsugu, suffering is entertainment. Even death becomes stimulation. He has never feared consequence until now. In his final seconds, he experiences humanity for the first time—pain, terror, limitation.

Shinzaemon decapitates him and then collapses. The noble death he sought arrives, but not as pure transcendence. It is messy, painful, uncertain. Fate has indeed smiled, but the smile is ambiguous.

The epilogue notes that Naritsugu’s death was officially attributed to illness. History sanitises violence. The state preserves its narrative. Yet twenty-three years later, during the Meiji Restoration, the Tokugawa Shogunate falls. The old order dissolves. The samurai class disappears. The assassins’ act becomes a footnote in a broader transformation.

What, then, is the film’s true subject? It is not merely heroism. It is not simply critique of tyranny. It is the psychological structure of a warrior ethos trapped in peacetime. The Tokugawa peace stabilised Japan for over two centuries. But peace, prolonged, produces dislocation for those whose identity is forged in combat. Shinzaemon’s smile is the smile of a man finally reunited with his function.

There is also a political warning. When institutions protect cruelty because of lineage, collapse becomes inevitable. Naritsugu’s impunity is systemic, not accidental. The Justice Minister’s recourse to assassination signals the breakdown of legitimate authority. The sword becomes corrective when law refuses to act.

Yet the film refuses simple glorification. Shinzaemon’s closing realisation suggests that fate’s smile is double-edged. The assassins achieve their goal, but the world they save will soon erase them. Their sacrifice accelerates a transition in which men like them no longer have a place.

Koyata survives improbably and departs toward a freer life, perhaps even toward America. Shinrokurō contemplates banditry. These endings hint at modernity: fluid, individualistic, detached from rigid hierarchies. The samurai code dissolves into improvisation.

Thus 13 Assassins becomes an elegy for a civilisation built on disciplined violence and strict honour. It recognises the beauty and the danger of such a system. Noble death can inspire resistance against tyranny, yet it can also romanticise self-destruction. The samurai live intensely because they expect to die decisively. For contemporary audiences, accustomed to valuing longevity and comfort, this worldview appears alien. And yet the film compels respect. In a world where power often hides behind bureaucracy, the willingness to stake one’s life against injustice retains a raw moral force.

Shinzaemon’s smile remains the film’s central enigma. It is joy and doom intertwined. He discovers purpose at the moment he commits to annihilation. His fate is sealed the instant he feels most alive. In that paradox lies the film’s haunting power: life sharpened by the certainty of death, honour pursued through self-erasure, and a decaying empire momentarily redeemed by men who know they will not survive it.

About the Creator

Peter Ayolov

Peter Ayolov’s key contribution to media theory is the development of the "Propaganda 2.0" or the "manufacture of dissent" model, which he details in his 2024 book, The Economic Policy of Online Media: Manufacture of Dissent.

Reader insights

Nice work

Very well written. Keep up the good work!

Top insights

Compelling and original writing

Creative use of language & vocab

Easy to read and follow

Well-structured & engaging content

Excellent storytelling

Original narrative & well developed characters

Expert insights and opinions

Arguments were carefully researched and presented

Eye opening

Niche topic & fresh perspectives

Masterful proofreading

Zero grammar & spelling mistakes

On-point and relevant

Writing reflected the title & theme

Comments (1)

He died doing what he knew/was trained to do, what made him what he was even if meant death He knew the old way was dying but had to cut out the cancer before it spread.... Excellent work....keep writing...