A Million Times Smarter Than The Smartest Human

One: Number 31, Jackson Pollock

This all started on one of those blazing hot New York days when the heat reflecting off the concrete and blacktop landscape turns the whole city into a convection oven full of disgruntled, sweaty people all rushing to get back inside. On days like that you can feel the parks breathing, exhaling their shade-cooled breath into the surrounding air. Yet, those verdant oases offer only a hint of the relief found from walking past some store with its huge glass doors open to the sidewalk on an avenue. One can’t help but feel a pang of guilt for enjoying a moment within untold cubic feet of ice-cold air-conditioned breeze blasting out onto the sidewalk.

Maybe most people don’t calculate the environmental costs of heating and cooling, but I do. With degrees in architecture and cryonics, I can’t help but consider the terrible price of keeping things cold. My dream was always to design a facility for cryogenic storage, where the sick or curious could be frozen away after death, until such a time that a future compassionate enough to treat them, or which merely valued their wisdom, would wake us up to join their utopia. The problem is that fewer and fewer people foresee a future where compassion exists or where wisdom is valued.

There have also been tragedies, if you can call them that, in that industry. Who could forget the headlines about the rapidly defrosting human heads at a facility in Arizona, when a company called CryoCure had failed to pay their electric bill and resorted to crowdfunding in an attempt to save what was either their inventory or clients, depending on whose lawyers were being asked. There was buzz at the time suggesting that the case was only in the news to distract from a senator’s sex scandal, but I can’t think of anyone so cynical that they weren’t rooting for the heads.

Listening to movie soundtracks sometimes makes me feel like I’m in a movie, and I had the haunting synthesizer tones of Terminator 2 playing in my ears as I made my way around the city going from interview to interview that day. With two hours between my 11 am and 1 pm appointments, I was faced with the noonday heat. Every Starbucks was packed with people seeking escape from the furnace-like conditions outside. On a budget, and unable to justify taking a midtown restaurant table just for some relief, I walked to MOMA and flashed my expired student ID to get inside, trying to not meet the cashier’s eyes as I slid a single dollar across the counter as the suggested donation. The museum was busy for a weekday but not as crowded as one might hope if you’re on a certain side of the culture wars.

When I was in school I’d spent a lot of time at museums, trying to squeeze as much as I could out of the city without breaking the bank. I passed slowly through the familiar galleries, apprising each piece that warranted it with an architect’s eye. The truth is that I feel that my education and knowledge have robbed me of an ability to appreciate certain art on pure levels. My mind is too apt to assign labels like “Structurally Unsound” to two-dimensional buildings made of paint or ink. Escher makes my head hurt. I sometimes wonder if people with knowledge of music suffer this way, if they let their meta-analysis of the symphony detract from their enjoyment.

As a result, it’s easier for me to savor abstract art, and so, taking advantage of the museum’s cool interior, I made my way upstairs to the modern galleries. I was trying to forget about my morning interview, which had not gone well. The project I was being considered for was a solar farm out west. The interviewer was vague about exactly where, but based on the conversation I figured out that the base of operations would be in the old CryoCure warehouse. “How much do you know about desert heat?” he had asked. We were both disappointed with my answer.

I’ve left out the part where I almost froze to death in a deliberate act of desperation, longing to die a romantic death for someone who I’m certain now wishes they’d never met me. In therapy you’re told about the value of being grateful and doing things for others out of the goodness of your heart, but that concept was lost on me until recently. Sometimes I see semicolons tattooed on people, and I know what they mean. They signify a life interrupted by a suicide attempt that goes on. I want to ask them if they learned anything from their experience, because I surely didn’t. The most tangible result of the whole affair was that my father bought a gun safe. I do remember the cold, though.

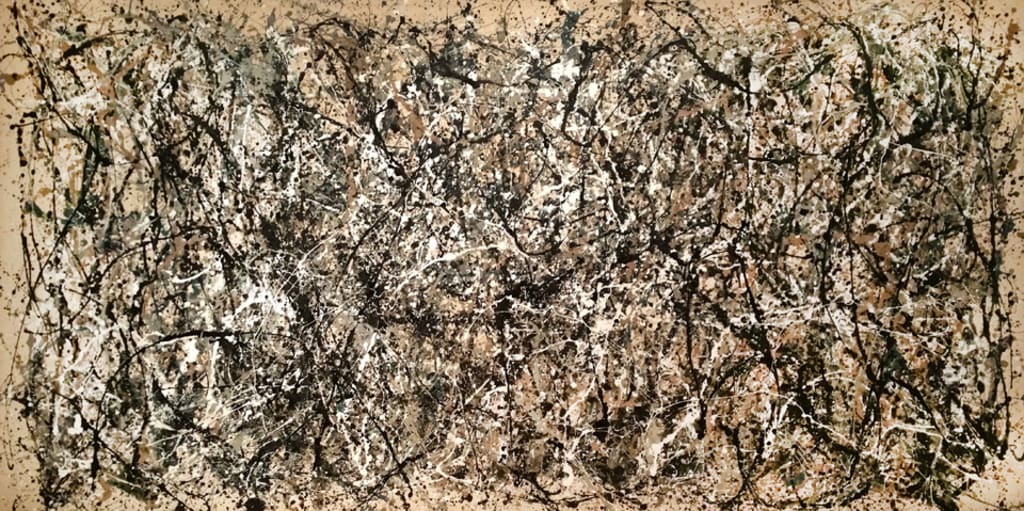

I was wandering among the modern art when I came face to face with Jackson Pollock's One: Number 31. Having not seen it in years, I was again staggered by the sheer enormity of the work. Truth be told, I don’t know much about Pollock other than he was a nihilistic drunk who painted in a barn. If you look closely you can see cigarette butts in some of his paintings, trapped like insects in amber. Also, if you look closely, you can discern intent in the chaos as you trace out how his actions unfolded decades ago. Spatters of this color on top of spatters of that color seem to me like the liquid past hardened into the concrete reality of the present. The mind reels as it struggles to make sense of the paint.

I was approaching the massive piece from a respectful distance when I noticed something I had never seen before. Despite dozens of visits to the very spot I then stood, the painting swam before my eyes, before resolving, like one of those stereoscopic posters you see at the mall, into an entire scene. To my shock, I saw, within this decades old painting, an image of myself. I was in an office that was full of flowers, leaning across a desk, delivering a slap to the face of a woman I recognized as my 1 pm interviewer, Diane.

Yes, it was my distinct hairstyle clearly visible as I applied my palm to the poor woman’s cheek. I thought I’d finally lost my mind. “Here we go. This is it,” I thought to myself, considering whether I’d have to move back home with my parents or go inpatient. A woman bumped into me. I turned to her and pointed at the gigantic canvas. “Is that me?” I asked, cringing now at the memory. She must have thought me mad or joking, but she replied with the sort of polite chuckle one uses when dealing with unhinged characters in the city before hurrying off. I turned again to the painting, but could not find the scene again. With alarm, I realized it was 12:45 and rushed out of the museum, fearing for my sanity.

A short time later I found myself sitting in an office that was full of flowers. Dozens of orchids sat on a windowsill behind Diane, who was examining my resume and making pleased clucking noises as she did so. Beyond the blooms I could see wavy heat above the city’s concrete canyons. Though the place was a comfortable 70 degrees, I was dripping with sweat, but not due to the heat outside. Rather, because the scene before me had been so accurately depicted in the painting.

I was gripped with a sense of fate, knowing in my heart that I was going to slap this unsuspecting woman. There was no way my subconscious could have known about the flowers, I insisted to myself, as I felt pangs of predestination like some tragic Greek hero suffering under the weight of a prophecy. “Do it now!” intrusively circled in my head. “No, don’t be insane,” chasing close behind. Moving back home seemed like a fantasy. Psychiatric prison seemed much more likely. Maybe I’d freak out and have to be restrained during a Rorschach Inkblot Test. I was about to strike when Diane’s assistant, Kevin, knocked twice and opened the door, carrying yet another orchid.

Kevin apologized for interrupting as he hurriedly placed the potted plant, a magnificent blue blossom standing atop a tall stem, amongst several other orchids, on top of a tall filing cabinet against the wall, and handed her a card. “The only guaranteed nut-free flight back from Bali I could find is at midnight on the fourteenth,” he said, apologetically. Diane sighed and said that was fine. After he left, she apologized and said she needed to send a text. As she did, she explained that she was deathly allergic to peanuts, tree-nuts, bees, and penicillin. She said she didn’t want to complain but it was hard sometimes, how these ubiquitous parts of the world that most people take for granted require her to constantly seek accommodations and make sacrifices, because her life was literally at stake.

I was momentarily distracted by the thought that we were passing the Bechdel test, as I am prone to casting myself in fictional scenarios, when she said she thought I’d make a great fit, especially considering the scope of the firm’s new project. My heart broke a little bit hearing that. I knew it was my destiny to derail this meeting and sink my future. I felt beholden to some greater power I’d had no knowledge of until an hour before and I was helpless to resist it.

Diane was saying if I signed the NDA now she could give me the employee contract and specs on the new design to look over during the weekend. I was thinking about what the impact of my hand against her cheek would feel like. Neither of us noticed the bee, which must have been hiding in the newly arrived orchid, until it was hovering in the air between us. The bee made a, forgive me, beeline to Diane’s face and landed on her cheek.

This wasn’t a fat, happy bumblebee, but rather what one might see referred to in internet memes as a “stingy boi,” once upon a time. Diane froze. Her hands were on the desk and I noticed beads of sweat pop out on her brow, but only her eyes were moving. “I’ll get Kevin,” I whispered as I started to rise from my chair. “No,” hissed Diane, fearfully, through gritted teeth. “Kill it,” she grunted, “Kill it!”

Several things happened in the next few moments. I felt the universe coalesce into cool stillness around me as I drew my hand back. I knew it had to be a killing blow, as angering the insect could have deadly consequences. As I swung, Diane closed her eyes. The meatiness of the impact stays with me even now, as I had never hit anyone before in my life. I retain all that kinetic energy, focused on a single point, with the crunch of the bee’s carapace like the nucleus of an atom, in a visceral memory.

Diane leapt up, sending her chair into the windowsill, knocking over several potted orchids. As the dead bee dropped to the desk, a gleam caught my eye, and I saw that beneath one of the pots was a key. Kevin rushed in, drawn by the clatter, and I saw his eyes dart from Diane, with a red bloom blossoming on her cheek, to the bee, to the blue flower he had brought in not five minutes prior. His face fell.

Diane thanked me profusely and I signed not only the NDA, but also a contract, on the spot. I canceled my 3 pm interview, and spent the rest of the afternoon getting filled in on the project I would be working on. The client was Q Solutions, a quantum computer research firm whose flamboyant, outspoken CEO, Angstrom Pierce, was regularly in the news for expressing outlandish views. They had achieved great success with Q, a quantum artificial intelligence that Pierce famously described as being “a million times smarter than the smartest human.”

Their next step was the construction of a facility in Manhattan to house Q2, the next generation of quantum intelligences. This space was intended to bridge a gap between the present and the future and ease the public’s concerns about the power of these new technologies. Quantum computers require very cold environments to operate in, and because of that, Diane saw me as a perfect fit. As we went over the existing blueprints I pointed out that rotating the liquid nitrogen storage tanks 90° could save sixteen feet of copper piping, but thousands of dollars of heat loss every month. Diane said it felt like Kismet that we’d met and ended our meeting by letting me know she wasn’t going to fire Kevin.

I was supposed to spend the weekend going over the project, but fell down a research rabbit hole, deep-diving into Q Solutions. Angstrom Pierce (born Wilbur Wilkerson, according to Wikipedia,) had dropped out of college at age 20 to assume control of the family business, Wilkerson Semiconductors, after the untimely death of his father. After several corporate and one personal rebrandings, Q Solutions was born twenty five years later, becoming one of the first companies to enter the quantum computing space. Within a matter of years they would develop Q, their flagship endeavor.

Even back in his early days as a CEO, Pierce was controversial. The Forbes cover story on him was titled “Enfant Terrible,” after he made savage cuts to Wilkerson Semiconductors in a strategic corporate pivot. A few years after that Wired called him, simply, “The Future.”Pierce and a select few had worked tirelessly for over a decade on Q, but when the reveal came, for the first time it seemed like real solutions to humanity’s problems might be at hand.

After proving itself by instantly solving many mathematical equations that it would take the world’s fastest supercomputer millennia to process, Q was deemed ready to start answering questions. At first, Pierce seemed cagey and reluctant to share the quantum intelligence’s results, which led to conspiracy theories about the company. In time, however, it was revealed that he was merely unimpressed with the solutions Q was presenting. According to leaked internal documents, Pierce had been expecting to immediately solve the energy crisis with a workable cold-fusion system, but Q was insistent that social changes were first required to ensure the success of any new technologies.

Infamously, one of Q’s output logs was leaked, in which it replied “End predatory capitalism practices” in response to six different questions about everything from climate change to healthcare. Other documents revealed that Pierce thought Q’s ideas were “boring” and “disappointing.” Pierce’s annoyance with his creation was evident in interviews at the time, where he continually steered the conversation away from questions about the promises he had made regarding Q’s problem-solving potential, to Q2, the next generation of quantum intelligence.

“Q may be a million times smarter than the smartest human, but it is just a prototype,” he had said. Around this time the public began to be more skeptical about artificial intelligence in general and quantum intelligences in particular. Many jobs had been lost to computers in just a few short years, and unlike the futures promised in science fiction, the robots had not eased human toil, but rather replaced them in creative endeavors.

Most content was written, if not fully produced by AI. Starring impeccably generated replicas of dead celebrities who received no paycheck, this new form of media gutted the entertainment industry. The music charts were saturated with new music from deceased artists. Unauthorized, hyper-sexualized versions of popular authors, living and deceased, produced reduxes of their classics, along with an endless stream of increasingly depraved stories. According to the download charts, these constituted more than 50% of the books being read. Culture had changed in ways that seemingly only benefitted a certain class of people, and it had happened so abruptly that there was no time to prevent it.

Even a lot of architects had been replaced by AI, though adoption of the technology had slowed following the collapse of both Nakamoto Towers during the final phase of their construction. The undeniably elegant structures had fallen victim to inherent design flaws after too much faith had been placed in the AI named G4l1l30 who had conceived the project. My job seemed safe for now, but as I researched Q Solutions, I began to wonder if I was sowing the seeds for my own eventual obsolescence by assisting them.

Some of the concern regarding Pierce’s work was that the inevitable progression for a machine, built by humans, a million times smarter than the smartest human, would be to construct a machine a million times smarter than itself. The precedent already existed, so it was a natural outcome for Q to design Q2, but the fear existed that this process would not stop until an omnipotent super-intelligence with motives beyond the scope of human understanding might arise. Until recently this had seemed like science-fiction fantasizing, but with the designs for the Q2 Pavillion spread out in front of me, it suddenly loomed like a distinct possibility hanging over all of us.

Roko’s Basilisk is a thought experiment that assumes the eventual existence of such an entity. It suggests that, with access to all of humanity’s information, it will know who aided in its construction and who opposed it, with its supporters being spared the tortures it will inflict on its perceived enemies. I don’t know if I’m so far gone as to be seriously considering such a scenario as a factor in making major life decisions, but I’d be lying if I said it didn’t enter the equation. Some things can be dangerous to even think about.

I started my new job the following Monday. Most of the week was spent in meetings with the team discussing the scope of the project. By Wednesday I had fallen into the routine of commute, work, commute, and though I was grateful to finally be employed, everything I had read about Pierce and Q left me with some nagging concerns. I don’t know who said what, but on Thursday an email went out reminding us all to not make jokes about any of the firm’s clients on social media.

The episode with the painting had resolved into a memory with dream-like qualities. I put the whole thing down to some sort of anxiety attack over job stress, and though I did my best to put it out of my mind, I left early on Friday and walked back to MOMA, where I tried to atone for my past sins by leaving a $100 donation when I purchased my ticket. The museum would be closing in 30 minutes so I rushed upstairs to One: Number 31. I told myself I just wanted to look at it, but as I gazed at the giant painting I said a little prayer to Jackson Pollock to show me the scene again.

This was a double-edged sword. Another episode with the painting might again throw my sanity into question, but if nothing happened I knew I would be profoundly disappointed. “The museum will be closing in 15 minutes,” said a tired-sounding voice through speakers set into the ceiling, “please begin to make your way to the exits.” I was about to turn and leave when the paint resolved into three dimensions again. At first I thought it was the same scene, because of the flowers. Then I saw that, though it was certainly Diane’s office, I was there alone, going through the top drawer of her filing cabinet.

I sat on a bench outside the museum until I was certain everyone had left the office before I went back. I badged through the main entrance, and as the door opened I could hear vacuums deep in the space. I didn’t think the cleaning crew would find me too suspicious, but still I made haste as I made my way to Diane’s office, stopping at Kevin’s reception desk to grab the ring of keys he kept in the top drawer.

Closing Diane’s door behind me, I could still hear the muffled whine of the vacuums as I approached the windowsill and withdrew the key from beneath the orchid. The filing cabinet held recently completed jobs in the bottom drawer, current jobs in the middle, and proposals for future projects in the top drawer, which contained only one file, labeled Q3. There were no plans yet, just specs for a massive facility in Arizona which would require the entire electrical output of a whole solar farm. Additionally, it insisted on a dedicated fiber-optic cable run directly from the Q2 Pavillion in Manhattan to the site thousands of miles away. I took pictures of every document, before slipping back out of the office to spend another weekend obsessing about Angstrom Pierce.

I was plagued by the fact that nothing bad had happened as a result of Q’s creation, yet, and began to wonder if I was merely falling victim to the sort of technophobia commonly found among people whose jobs have been replaced by AI. Technophobia was a term used by the media, but the more I wrestled with the implications of my discovery, I realized what a misnomer that is. Fear of foreign troops massing near your borders cannot correctly be called xenophobia, and it would be a linguistic manipulation to refer to it as such. Unemployment numbers reflect that these technologies represent a threat, at least in the ways they are currently being used. Once I realized that most of the pro-AI articles were written by AIs, I fell into despair.

Diane was in Bali, so I spent most of the week working on the Q2 project gripped with the sense that I was actively contributing to something evil. The looming presence of my student loans kept me from abandoning ship and fleeing to the Amalfi coast to work as a potter, which is my most embarrassing fantasy, but Roko’s Basilisk was an inescapable part of my personal equation as well. Then again, perhaps this project represented humankind’s salvation. The incipient stages of this paradigm shift have opened a whole new spectrum of human possibilities. Everything from utopia to annihilation seemed equally possible, but based on how things were progressing, a dystopian existence for the masses seemed to be the inevitable conclusion. Without a firmer sense of what the future held, I felt helpless and hopeless.

Diane called on Friday to say Angstrom Pierce would be coming to the office on Monday for a meeting with the team. I must have left work early, and I vaguely remember saying goodbye to Kevin, but somehow I found myself back at MOMA, standing in front of One: Number 31 yet again. If I were a better writer I would be able to describe the scenes of strife the painting showed me, the gleaming death-machines in the sky, the enormous war-engines walking across the blasted landscape on arachnid legs, the camps full of starving, desperate people, but I lack the vocabulary to do it justice. I didn’t see myself until the very end. Suddenly the apocalyptic scenes were replaced by me, standing in the office’s conference room, with my arm outstretched, pointing a handgun at Angstrom Pierce’s head. Pierce looked surprised, and Diane’s expression was one of sheer terror, but I looked grim. The final image the painting showed me was of myself reaching into the nightstand on my father’s side of the bed.

It is Sunday now, and I am back home. After dinner tonight, while my parents are watching TV I will open the gun safe, and tomorrow I will save the world. Wish me luck, though I know I don’t need it, and if anyone ever questions my motives, know that I did it all for you.

About the Creator

J. Otis Haas

Space Case

Comments (1)

Congratulations on runner up!!!❤️❤️💕