'Till Death We Do Art

Why making art might be the only divine act left to us.

There would be nothing divine in this world without art.

Nature may surpass the divine to all intents and purposes, but like everything it absorbs and is absorbed by, it remains here, stuck on the surface of this world, ever-present, physically bound to the universe.

Sex, as the sacred animalistic (and therefore human) ritual of pleasure, of violence, of love, of procreation, excels among our experiences.

Yet nothing is divine but art.

Our acts of creation either bring us closer to understanding God — or the Creator, if it exists — or are nothing less than the creation of God itself. Through the birthing of our creativity and imagination, we become something truly unique in nature.

We are, altogether, the created and the creators.

A certain eagle-eyed view on life reveals how easily we get caught up in endless work. We constantly strive for more scientific progress. We obsess over so many things.

And then… we die.

Memento mori strikes each person differently; their impact, and the reasons behind it, are as countless as the shifting elements that make up a human life.

But one perspective, simple though it may be, feels worth holding onto: we are going to die, so we may as well make art.

We may as well create, delight in beauty, and lose ourselves in the highest pleasures of the senses, so long as no harm is done.

Music is a drug without an addiction. An addiction without a drug. Music enjoyment was a mystery for a while, as it appeared to have no survival purpose.

Music may have had evolutionary purposes through social cohesion, emotional expression and incitement, and influencing cognition. Or it may have been a byproduct of human activities and processes, such as language.

“The music you love tells me who you are. It’s autobiographical. Our brains link music with memories, emotions, and identity.”

— Daniel Levitin, This Is Your Brain on Music

No matter how you turn the frittata, few things can enlighten us, illuminate us, and give us pleasure like listening to music.

The need to create and respond to art is one of humanity's most defining aspects. Art is not frivolous but rather deeply integrated into how our brains understand and navigate the world. If music, perhaps the most abstract of arts, can do this, then all forms of art might function as complex cognitive exercises that shape how we think and feel.

Beyond science, religion, or money, art is how we communicate and understand the world as a social species — and an emotional one at that.

It is time we understood that evolution in the strictest sense does not drive the whole of our lives; it is not the only ultimate purpose.

Given how far we have “evolved,” we need something to make survival feel like it’s worth it.

Art, like love, gives us that.

Going to visit Yayoi Kusama’s exhibition in Melbourne this year was a psychotic trip, in all senses. But this artist in particular may be the peak example of living for art, or, more accurately, living within it.

Often a cacophony of dots, Kusama’s art is nothing less than Kusama herself.

“If it were not for art, I would have killed myself a long time ago.”

This statement is raw, but it resonates with Levitin’s idea that art (he spoke about music specifically) can activate emotional and cognitive systems in the brain that regulate distress and construct meaning. In Kusama’s case, art becomes a neurologically and emotionally essential act, organising chaos, channelling compulsion, and transforming suffering into beauty.

That’s the yolk: we cannot escape suffering, but we can make sense of it. Logic and psychology can be helpful, but they are often too limited in expressing or transforming the real essence of pain and pleasure.

When it comes to visual arts, Edvard Munch is, for me, more relatable.

Perhaps more than any other artist, Munch gave shape to the inner life and psyche of modern man and thus became a precursor in the development of modern psychology. His images of existential dread, anxiety, loneliness, and the complex emotions of human sexuality have become icons of our era. Most of us in the Western world recognise works such as The Scream, Anxiety, Jealousy, The Kiss, Madonna, Vampire, and The Dance of Life. During the 1890s, Munch developed these themes of Angst, Love, Sex, and Death in a project he called The Frieze of Life, to which he returned at the end of his life.

At the maximum elevation — the peak of conscious expression — there is the merging of music and visual art: poetry.

When I was younger (not that much younger, but happily under 30), I wrote a story titled Seeking Immortality Through Art. How to live forever. Or at least try. In it, I described how the creation of art can be attuned to seeking eternal life, remembrance, and one’s name written in the stars.

Now I see it perhaps less poetically and more like one of those Black Mirror episodes where consciousness gets uploaded to a cloud for an everlasting soul (for example, “San Junipero”).

That’s what I do, like it or not, with every single poem. Upload some memories, some dreams, some ideation to the cloud; whether that be a piece of paper, Samsung Notes, or this very website.

However, it does not intend to live forever.

It simply wants to be.

Emily Dickinson, Vincent van Gogh, and Henry Darger are just a few examples of living through art, even when no one had a clue. Or perhaps they did, at least in Van Gogh’s case, but he — like so many artists throughout history — created not for immediate fame, but out of necessity.

In the film Love (2015), the character Murphy says:

“I want to make a film that’s like a flame, like a storm, full of blood, sperm, and tears.”

Another way I like to frame the idea is through the famous saying, “art imitates life.” Or, perhaps better, the reversal: “life imitates art.”

In reality, they are the same thing.

About the Creator

Avocado Nunzella BSc (Psych) -- M.A.P

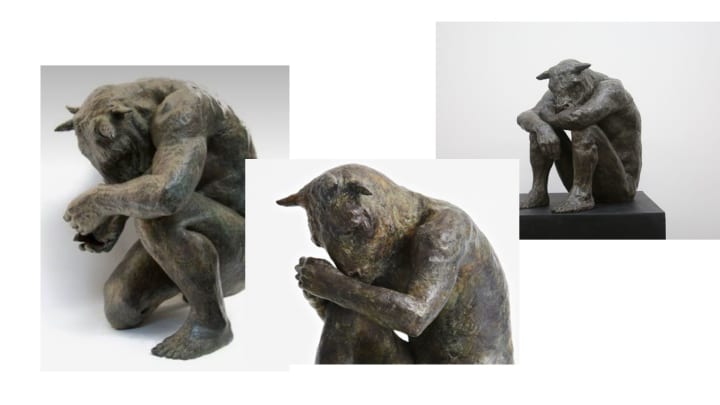

Asterion, Jess, Avo, and all the other ghosts.

Comments (1)

Yes. Art, quite possibly, is everything. ❤️