Critical Notes on Life’s Peculiar Circus

Bitter notes from life’s circus that never makes sense

Life, in its infinite generosity, insists on giving us problems the way a deranged clown tosses cream pies: one after another, straight in the face, without explanation, and with a grin so grotesque it borders on divine. People say that problems make us stronger, though no one has ever explained why strength should be such a desirable state. After all, the strongest creatures on this planet are cockroaches, who can supposedly outlive nuclear winters. And yet no one erects monuments to them, nor do they get motivational posters. Humanity celebrates strength while quietly hoping never to need it—like buying a fire extinguisher and praying it will remain untouched, collecting dust and guilt in the corner.

The truly absurd part is that most of our problems are manufactured by ourselves, in the grand tradition of self-sabotage that seems written into our genetic code. We invent money, then agonize over not having enough of it. We devise governments, then complain about their corruption as if corruption were some unexpected side effect rather than the natural flavor of power itself. We create gods, then tremble before them, puzzled when these gods resemble suspiciously tyrannical landlords. If an alien anthropologist were to visit Earth, their report would simply read: “The species generates puzzles for itself and then suffers indignantly when it cannot solve them.”

There is a cruel irony in how the most pressing human problems are often invisible, unmeasurable, and almost certainly unsolvable. Loneliness, for example, is not counted on GDP charts. You cannot measure despair in liters, nor can you weigh meaninglessness on a kitchen scale. And yet these intangible torments drive people more effectively than hunger or cold. A man with an empty stomach may survive; a man with an empty sense of purpose may very well pull the plug himself. That is life’s joke: it demands that we continue breathing in a universe that can’t even bother to provide subtitles.

The advice culture, of course, makes everything worse. Everywhere one turns, there are instructions for “happiness.” Ten steps, five hacks, three spiritual rituals involving Himalayan salt and goat yoga. They tell you to think positively, which is essentially like telling someone with a bullet wound to imagine rainbows instead of calling an ambulance. Positivity is not a cure; it is a sedative. We are encouraged to meditate while standing on metaphorical burning buildings. And when that fails, society simply says, “Well, you didn’t try hard enough.” The blame shifts neatly back to the sufferer, who is conveniently too exhausted to protest.

Love, the great intoxicant, is another cosmic prank. People chase it as though it were oxygen, and perhaps it is, but oxygen at least does not abandon you after a heated argument over dirty dishes. Love promises transcendence but delivers paperwork, jealousy, and someone else’s snoring. It is a contract written in invisible ink, always expiring at the worst moment. And yet, absurdly, we return to it, again and again, as moths to a lamp that burns them every time. Perhaps we return because the alternative—solitary existence—is simply too humiliating to admit. To die alone is the greatest modern horror, which is laughable, considering everyone dies alone anyway, no matter how many clasped hands surround the bed.

Then there is work: the great charade of productivity. We devote decades to filling forms, typing emails, stacking boxes, pushing digital numbers around like children playing with sandcastles that the tide erases. Work is presented as noble, when in fact it is a polite way of saying that without constant distraction, people would notice how futile existence really is. Capitalism, in its brilliance, has managed to turn despair into an economy. The fact that many spend more hours in fluorescent offices than under natural sunlight is proof enough of humanity’s submission to its own inventions. One wonders if future historians—if there are any left—will marvel not at our wars or technology, but at our willingness to sacrifice entire lifetimes to tasks whose memory dies the moment we retire.

As for morality, it is perhaps the most absurd invention of all. Each culture scribbles a different rulebook, then insists theirs is the universal edition. Murder is wrong—except in war. Theft is wrong—unless conducted by corporations through loopholes. Lying is wrong—unless you’re a politician, a parent calming a child, or someone on a first date. What we call morality is merely convenience wrapped in poetry, a flexible code written by winners to keep losers in line. And yet, without morality, civilization collapses into teeth and claws. It is the ultimate absurdity: humanity trapped between rules it doesn’t believe and chaos it cannot survive.

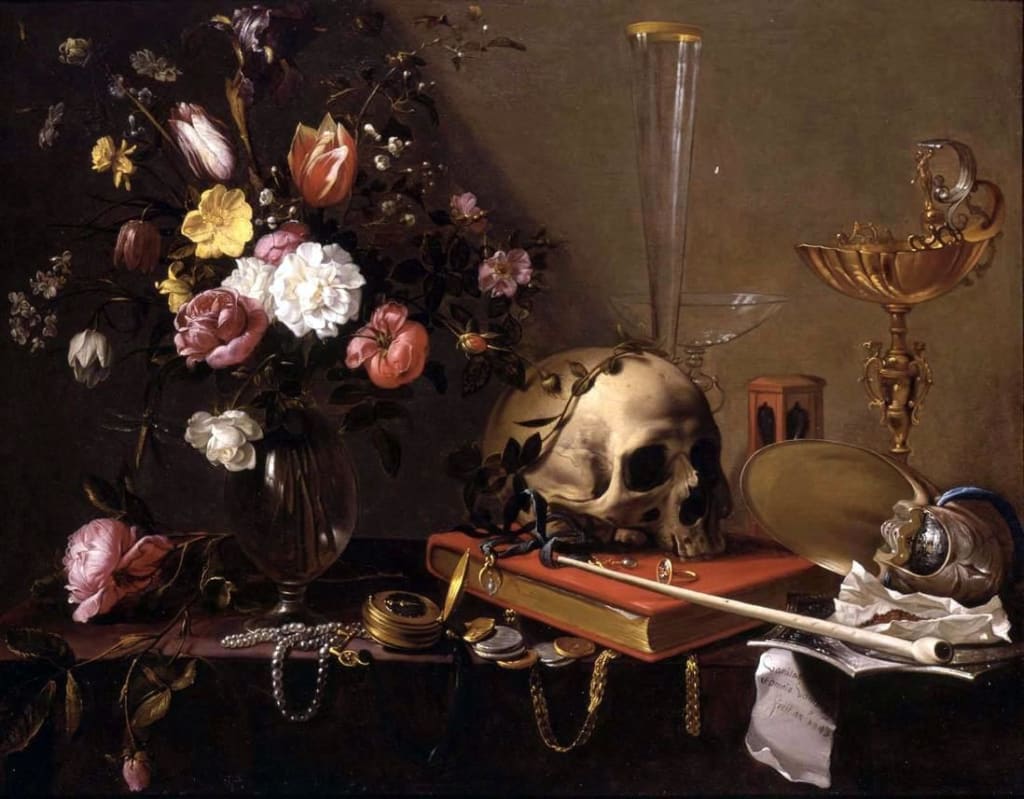

Death, naturally, is the only reliable solution, the full stop at the end of life’s nonsensical sentence. Yet it is the one subject that society avoids, as if refusing to mention it will make it vanish. Funerals are performed with mechanical solemnity, but no one truly believes the scripted platitudes. “They’re in a better place,” people whisper, as though eternity were a holiday resort with good weather. The reality is simpler: decomposition. Ashes, worms, and silence. The only mercy is that the dead no longer need to endure motivational seminars or office meetings.

And so we continue, marching forward, inventing meaning as fast as it dissolves, clinging to illusions with white-knuckled determination. Cynicism, contrary to popular opinion, is not despair but clarity—the recognition that life is a play performed without a script, in which the actors argue over costumes while the stage itself burns. The absurdity lies not in the fire, but in the fact that the audience applauds anyway, too terrified to admit the show was never worth attending.

In the end, perhaps the only sane response is laughter—not the joyous kind, but the sharp, bitter laughter of someone who has seen the machinery backstage and knows the whole thing is powered by rust and duct tape. To laugh is to admit defeat with style, to transform the unbearable into something momentarily tolerable. Because if life insists on being ridiculous, the least we can do is join the comedy troupe, smearing greasepaint across our faces as the curtain falls.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.