Alcestis and the Veil of Patriarchy

Unveiling the Silent existence and the Generational repression in Euripides’ Tragedy"

Alcestis

Euripides’ Alcestis is mistakenly interpreted as a tragedy about love and sacrifice, where a devoted wife willingly dies in the place of her husband, only to be later brought back from the dead by Hercules.

Many view the play as a commentary on female oppression within marriage, with Alcestis embodying the self-sacrificing wife. However, this interpretation, while valid, does not capture the full extent of its relevance. The dynamics of oppression within the patriarchal family extend beyond the role of the wife. They entrap all family members, particularly the children, who are destined to either inherit the role of Alcestis, as voiceless and sacrificial individuals, or that of Hercules, as an ignorant but celebrated male who will eventually conform to the patriarchal structure and become the next Admetus.

The father remains the unchallenged ruler, the Admetus of the household, benefiting from the sacrifices imposed upon others. This article will explore how Alcestis offers a deeper reflection on family roles within patriarchal systems and how these roles extend beyond gendered oppression into a broader mechanism of control and submission.

The Sacrifice of Alcestis

What can we say about Alcestis’ love? What can we say about a woman who died in place of her husband, only to return from the dead as a veiled figure?

As she lies dying, she acknowledges that her sacrifice will grant her kleos (glory), and this idea fascinates her. Yet, she is more concerned that this glory be bestowed upon her husband and children rather than herself. With clear and rational arguments, she explains that she chose death rather than living as Admetus’ widow because she believed that, given the circumstances, her death would best serve the very thing she had dedicated her life to, her marriage and household. Her entire existence is defined by the ideals of husband, children, home, and marriage, ideals that she upholds through her self-sacrifice. The only request she makes in return is that Admetus never remarry, and that she not be replaced.

With Alcestis’ departure, the first part of the play ends, and we, the spectators, go into mourning. Admetus orders all citizens of Thessaly to cut their hair and cease their music. Yet, soon after, the arrival of Hercules shifts the tone of the play entirely. Strangely, Admetus's need to uphold the virtue of hospitality proves more significant than his grief.

The Birth of Children: The Arrival of the Stranger

When the chorus, often representing the voice of the audience, questions Admetus about hosting a guest in the midst of such misfortune, they exclaim: "What are you doing? Do you welcome strangers amidst such sorrow? It is madness!" Here, the arrival of Heracles can be compared to the birth of a child. Just as Alcestis, as a wife, is transformed from an individual into a tool of sacrifice, the mother in a patriarchal household undergoes a similar transformation. She ceases to exist as an autonomous being; her only purpose becomes the child or, in the play, the accommodation of the guest. The needs of the child, much like those of the stranger, override her own, even surpassing the proper rites of her own metaphorical funeral.

Admetus, according to myth, was punished because he forgot to offer the appropriate sacrifices to Artemis on his wedding day. Apollo, indebted to him, granted him the alternative of having someone else die in his place. The origin of the tragedy ties into a broader pattern of patriarchal negligence.

The Child’s Awakening to the Tragedy

Heracles, upon realizing what has happened, exclaims in shock: "Ah! Why did you not tell me that the queen had died, and I sat here feasting and drinking for days?" All the while, those around him are dressed in mourning, cut hair, black clothes, and tear-streaked faces.

Heracles, in this interpretation, represents the child, either a son or a daughter, who, during adolescence, comes to understand the suffering and violence endured by Alcestis, their mother. The daughter, if she follows patriarchal expectations, will become another Alcestis. If she refuses, she can carve out her own independent identity, but society will punish her for it, and definitely not approve of her choices. The son, due to his maleness, has two paths: to become another Hercules, ignorant yet celebrated, upholding the patriarchal system and benefiting from its sacrifices, eventually to become Admetus himself. Or to fight against the societal roles of the Patriarchy, against the self-inflicted prophecy of becoming another Admetus. I will explain this further in the article.

The Return of Alcestis: A Voiceless Resurrection

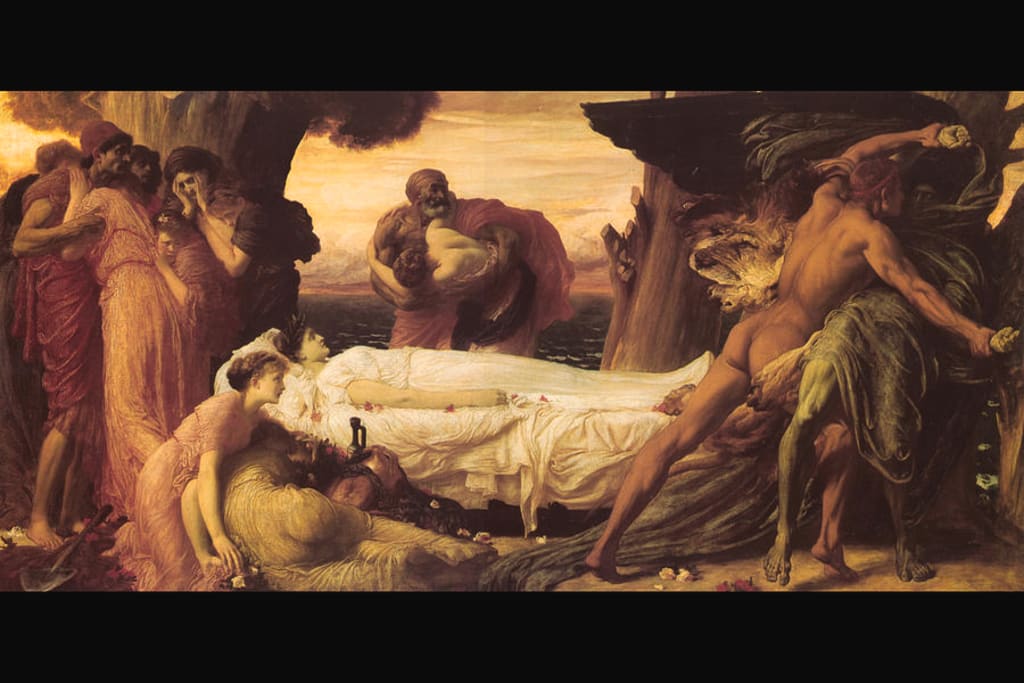

Heracles wrestles with Death and brings Alcestis back to life. At first glance, this might seem like a happy ending. Death is conquered, and a funeral transforms into the return of "normality". But there is a crucial ambiguity in the final scene that changes everything.

When Alcestis returns, she stands silent and veiled. We never learn what she thinks or feels about the reversal of her sacrifice. She remains a body without a voice, exchanged between two men. Heracles, the son in this analogy, reassures both Admetus (the father) and the male fear of a woman's power and independence, a fear embodied in Greek culture by figures like Helen of Troy, Clytemnestra, and Medea.

Breaking the Cycle: The Son’s Alternative Path

While Admetus in our analogy continues to uphold patriarchal power, not every father must be Admetus, nor must every son be Heracles. The son has an alternative: rather than resurrecting his mother to relive her oppression, he can reject the patriarchal system entirely. If he arrives too late and the sacrifice has already occurred, his role is to confront the father, to refuse complicity. If he arrives in time, he must prevent the sacrifice altogether, standing with the mother rather than perpetuating the cycle. The true alternative is to demand that the father bear responsibility rather than using Alcestis as a sacrificial lamb.

Euripides’ Skepticism of Patriarchy

Alcestis is glorified as the best of women, not only by her husband but by the chorus as well. Society idealizes her for the very choice that led to her oppression. It upholds a model where a good wife values her husband’s life above her own. However, Euripides does not necessarily endorse this model; on the contrary, he challenges it. His portrayal of Alcestis as a silent, enigmatic figure at the end of the play raises doubts about the supposed virtue of this ideal. Some critics mistakenly argue that Euripides supports patriarchy in Alcestis, but such interpretations reflect a lack of understanding. In reality, his questioning of these societal norms, 2,500 years ago, is nothing other than revolutionary.

When Heracles brings Alcestis back, she is neither fully alive nor fully dead. She is an object exchanged between men, a mystery crucial to the collective imagination of the male spectators in the ancient Greek audience. Greek tragedy was performed exclusively for male spectators, making this final moment particularly significant. Alcestis stands at the threshold of life and death, of presence and absence. When Admetus takes her hand, he recoils in fear: "Why is her hand cold? It feels as if I am touching death itself."

Alcestis does not speak. She says nothing. No one asks her to speak, no one explains what happened or what awaits her. Everyone celebrates, yet she stands in silence. Again. Just as before. A woman without a voice, a ghost of a woman. Her return is no true redemption t is a continuation of the same painful existence.

Alcestis' silence itself is also ambiguous, the seemingly happy ending is ironic and dual in meaning. Admetus is terrified because, as he lifts the veil, he looks upon the truth for the first time. Sometimes, in our analogy, Admetus, representing the father, can recognize the violence of patriarchy and has the choice not to perpetuate it but to break the patriarchal chains. That is why, in my analogy, I do not portray all fathers as monsters. However, in the case of Admetus at the end of the play, it appears that he ultimately chooses to maintain patriarchal power. Of course, not every father is Admetus, and not every son is Hercules.

The question is what one does upon recognizing the trauma upon realizing the role. Upon understanding that Alcestis’ return is not redemption, but repetition. That nothing changes unless one chooses to break the cycle. Euripides leaves us with a haunting question: Can anyone escape the roles assigned to them, or are they doomed to repeat the same patterns indefinitely? This is the ultimate tragedy of Alcestis, not her death, but her inability to escape the silence that defines her existence.

Conclusion

Euripides does not offer us a self-evident tragedy, but a drama full of questions. He does not allow us to be certain whether this is a story of salvation or condemnation, triumph or tragedy. Alcestis' sacrifice is framed as noble, yet it is clear that her role is neither liberating nor voluntary. Her death, as we later learn, is not a singular act of heroism but a tragic recurrence within a cyclical system that strips women of their voices. He challenges the patriarchal perspective, exposing its greatest fears and forcing them into paralysis. The final scene, where Admetus lifts the veil to confront the truth, is the key to understanding the tragedy. Euripides presents us with a choice: to accept the cycle of sacrifice or to break it.

In my mind, what I am inspired to say after reading Euripedes' play is to reject the demand for sacrifice, and to support a different future where individuals are not bound by oppressive family roles. Through this lens, Euripides' tragedy serves as a profound critique of patriarchal power structures, a critique that remains relevant today.

Written and published by Sergios Saropoulos

References

Arkoumanea, Louiza. "Το αίνιγμα της Άλκηστης." Lifo Podcast.

Rabinowitz, Nancy Sorkin. Anxiety Veiled: Euripides and the Traffic in Women. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1993.

Blundell, Sue. Women in Ancient Greece. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995.

Foley, Helene P. Female Acts in Greek Tragedy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001.

Loraux, Nicole. Tragic Ways of Killing a Woman. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987.

Zeitlin, Froma I. "Playing the Other: Theater, Theatricality, and the Feminine in Greek Drama." Representations, no. 11 (1985): 63–94.

About the Creator

Sergios Saropoulos

As a Philosopher, Writer, Journalist and Educator. I bring a unique perspective to my writing, exploring how philosophical ideas intersect with cultural and social narratives, deepening our understanding of today's world.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.