The Cognitive Mechanics of Getting Stuck

If your task doesn’t “fit,” your brain can’t grip. Learn how to fix Flexion.

Have you ever stared at a simple task, maybe sending an email, filing a form, or reading a short article, and found yourself paralyzed? The task is not hard. It is not beyond your capability. You even understand why it matters. But for some reason, it feels ungraspable. No traction. No flow. Just cognitive friction.

In these moments, what you are likely experiencing is low Flexion.

Flexion is not a term you’ll find in most productivity guides or clinical manuals. But it is central to a growing field of study in cognitive psychology known as Cognitive Drive Architecture (CDA). CDA is not a motivational framework or behavioral checklist; it is a structural field that models effort as a system property. It focuses on the internal configuration that makes action possible or impossible, treating effort not as a mood or trait but as an emergent outcome of interdependent variables.

At the heart of this model is Lagunian Dynamics, the core theory of CDA. It defines Drive, the system’s readiness and ability to take action, as the outcome of six interacting variables. One of the most crucial of these is Flexion.

What Is Flexion and Why Does It Matter

In CDA, Flexion is the variable that describes task–system fit. It is a measure of how well the task’s structure aligns with your current cognitive state. It is not about difficulty or complexity. Instead, it reflects how “grippable” the task is to your mind at that moment.

Imagine trying to grip a rubber band with frozen fingers. The problem is not with the band. It is with the hand. The same can happen with tasks. A task that looks perfectly doable on paper may resist your attention if it lacks Flexion.

Flexion is often confused with interest, but they are not the same. You can be deeply interested in something yet unable to engage with it if Flexion is low. Flexion is not about how much you like the task. It is about how smoothly your mind can wrap around it.

What Happens When Flexion Is Low

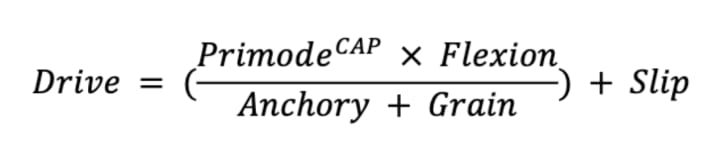

When Flexion is low, Drive cannot form properly. According to Lagun’s Law, Drive is computed from the interaction of six core variables: Primode (ignition threshold), CAP (activation strength), Anchory (attention stability), Grain (resistance), Slip (variability), and Flexion.

The equation looks like this:

Here, Flexion appears directly in the numerator. That means when Flexion drops, the system’s overall Drive output can collapse, even if everything else is aligned.

This collapse feels exactly like what people describe during moments of strange inertia. “I know what to do; I just can’t seem to do it.” “I’m not tired, but I feel locked out.” These are not failures of willpower or discipline. They are structural mismatches.

Why a Task Might Feel Rigid

Several factors can reduce Flexion, making a task feel more rigid than it actually is:

- Mismatch in abstraction: If the task is too conceptual and your brain is in a concrete state, or vice versa, it won’t connect.

- Poor emotional resonance: Even meaningful tasks can lack resonance in the moment. If your affective tone is low, the task might feel flat.

- Cognitive misalignment: Your brain may be in a divergent mode (idea-generating) while the task demands convergence (focus, precision). This mismatch creates drag.

- Unprocessed background load: Latent Task Architecture (LTA), a related theory in CDA, shows how unresolved tasks in the background can interfere with current task Flexion. These “latent loads” act like background noise, degrading fit.

- Temporal displacement: Some tasks feel off simply because the moment isn’t ripe. Flexion is highly time-sensitive. What fits at 10 AM may not fit at 4 PM.

When any of these are true, the task becomes cognitively “rigid.” It doesn’t bend to your shape. And just like a shoe that doesn’t bend, you can’t run in it.

How to Improve Flexion

The good news is that Flexion is not fixed. It is dynamic and modifiable. Here are several ways to improve task Flexion:

1. Reframe the task

Sometimes a task lacks Flexion because of how it is mentally framed. Try restating the goal in more immediate or concrete terms. For example, instead of “write a report,” try “list three things I want the reader to understand.”

2. Align state before forcing action

If your system is in a scattered or withdrawn state, no amount of pushing will help. Use a short cognitive warm-up to shift state. This might mean reviewing context, listening to relevant audio, or visualizing outcomes.

3. Inject novelty

Flexion rises when a task feels novel or freshly relevant. Even changing the interface, switching tools, using a different space, or changing the visual format can increase cognitive pliability.

4. Reduce latent load

As LTA explains, unresolved background tasks can pull against Flexion. Try offloading lingering to-dos or journaling out what else is on your mind before re-engaging. Reducing this load can significantly increase grip.

5. Use micro-goals

Tasks often feel rigid because their structure is too large or vague. Breaking them into micro-units with clear entry points increases Flexion. Think in five-minute slices.

What Low Flexion Is Not

It is important to clarify that low Flexion is not laziness, disinterest, or incapacity. These interpretations can lead to unnecessary guilt or self-criticism. In reality, low Flexion is a structural condition, a temporary mismatch between the task’s structure and the mind’s configuration.

In clinical and educational contexts, this distinction is especially vital. Research from CDA applied to ADHD populations shows that Flexion is a major contributor to the “effort paradox” when individuals with high motivation and ability still struggle with basic tasks. They do not lack drive. They lack fitness.

A Language for What Used to Be Invisible

Flexion gives us a precise term for an experience that many people have but could not explain. Before this concept, we might say “this task feels wrong” or “I can’t seem to start,” without knowing why. With Flexion, we gain diagnostic clarity.

This is one of the promises of CDA and structural cognitive models more broadly. They offer a shift from moralizing behavior to modeling it. Instead of assuming that motivation is missing, we ask what configuration is misaligned.

Flexion shows us that even when the task is simple, the system still needs a good fit. No matter how strong the engine, a car won’t move if the wheels don’t grip the road.

Final Thoughts

The next time a task feels oddly unyielding, pause before pushing harder. Ask yourself: Is the task too hard, or is it simply too stiff? Maybe your brain can’t grip it, not because you’re broken or lazy, but because the fit is off.

And when the fit improves, when Flexion rises, you will not need force. The task will bend. And your mind will move.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.