Slip and the Foundations of Cognitive Drive Architecture

How Lagunian Dynamics Explains Variability in Effort as a Structural Feature, Not a Flaw

In cognitive science and psychology, fluctuations in mental performance are often attributed to motivation, distraction, or emotional state. While these factors undoubtedly play a role, a newly proposed structural field—Cognitive Drive Architecture (CDA)—suggests that the story of effort variability is more mechanically complex. CDA introduces a system-level theory for understanding how cognitive effort emerges, stabilizes, or fails, based on internal configuration rather than external conditions or surface-level traits.

At the heart of CDA is its core theory, Lagunian Dynamics, which formalizes the structural mechanics of Drive. Lagunian Dynamics introduces six interacting variables and organizes them across three operational domains: Ignition, Tension, and Flux. These variables are not treated as traits or capacities but as real-time configuration states that determine whether effort is possible, stable, or volatile. Among them, a particularly important and novel construct is Slip.

As defined in Lagun’s Law and the Foundations of Cognitive Drive Architecture: A First Principles Theory of Effort and Performance (Lagun, 2025), Slip represents structured entropy—a source of internally generated performance variability. Unlike distraction or procrastination, which are typically reactive and context-driven, Slip is endogenous to the system. It reflects a baseline condition of entropy present in all cognitive performance, even when motivation, emotional state, and task clarity remain stable.

“Slip models performance variability not as noise, but as a structural component of the system. It reflects stochastic internal variance driven by emotional residue, subconscious interference, or system-level entropy. Slip is not an error. It is a baseline condition of all cognitive performance” (Lagun, 2025, p. 7).

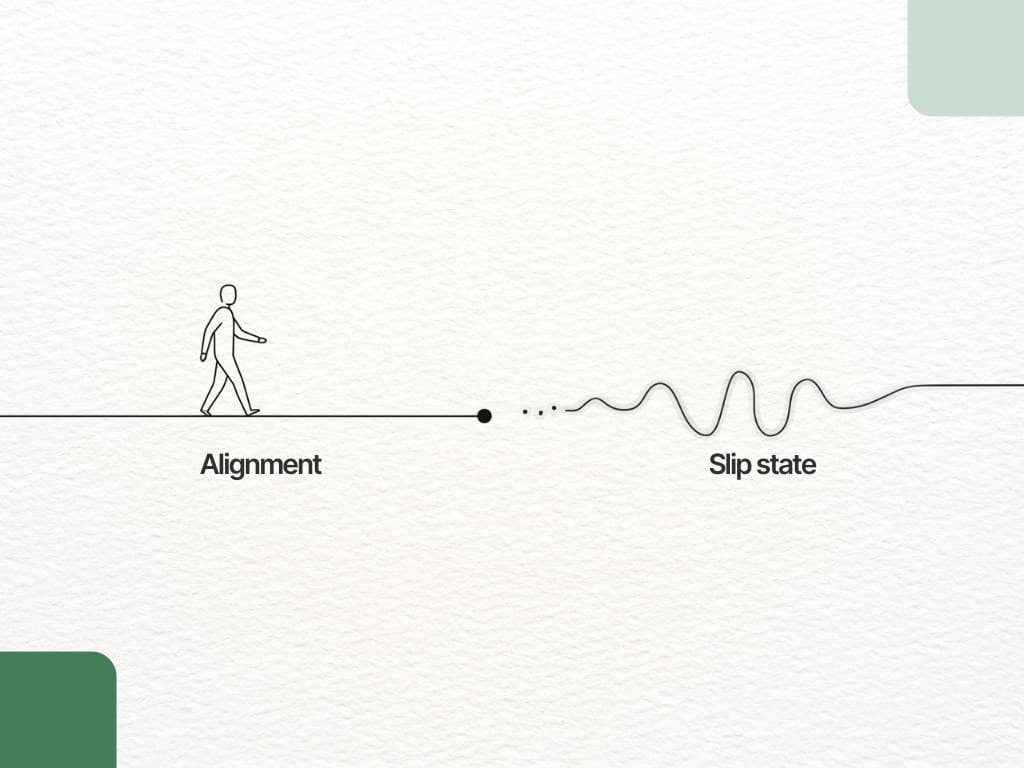

This framework offers a compelling structural explanation for a familiar phenomenon: days when a person is technically prepared—well-rested, informed, and focused in theory—but unable to fully engage. The task feels distant or brittle. Attention drifts. Productivity becomes erratic. Traditional models might attribute this to low motivation or weak self-control. CDA, by contrast, interprets it as a Flux domain event—a disruption in system coherence caused by Slip.

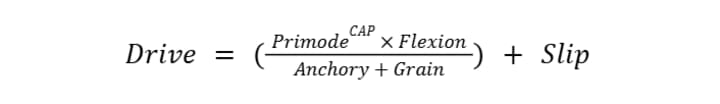

In CDA, Drive is not understood as a fixed resource or scalar trait. It is a computable outcome—the result of real-time interaction among six variables: Primode (ignition threshold), CAP (Cognitive Activation Potential), Flexion (task elasticity), Anchory (attentional tether), Grain (cognitive-emotional resistance), and Slip (structural variability). These are organized into the following domains:

- Ignition Domain: Primode and CAP govern the system's ability to initiate engagement.

- Tension Domain: Flexion, Anchory, and Grain determine the stability of sustained effort.

- Flux Domain: Slip accounts for fluctuations in performance due to internal noise and entropy.

Slip operates exclusively in the Flux domain and does not initiate or sustain action. Instead, it modulates the consistency and coherence of Drive once the system is active.

“Slip explains why a prepared, focused, well-resourced individual can still experience sudden disruption... Variability becomes legible, not random” (Lagun, 2025, p. 4).

This leads to a significant shift in interpretive stance. Rather than asking, “Why am I off today?”, CDA reframes the question: “What configuration has shifted in my system?” This distinction moves away from explanations based on static personality or external conditions and toward dynamic, structural assessments.

CDA identifies three additional variables—Flexion, Grain, and Anchory—that interact closely with Slip:

- Flexion: The degree to which a task conforms to the mind’s current structure. High Flexion indicates adaptability; low Flexion signals friction.

- Grain: Represents emotional or cognitive drag that impairs attentional cohesion.

- Anchory: The strength of attentional tethering; its degradation leads to fragmentation or drift.

Misalignments in these variables amplify the impact of Slip, creating conditions where effort becomes unstable despite clear intent and capability.

These dynamics are formalized through Lagun’s Law, the core equation of CDA:

Here, Drive is the net output of internal system alignment. Slip appears as an additive variable, representing internal entropy that disrupts Drive’s regularity, even under optimal conditions. The inclusion of Slip as a structural term, rather than noise or error, distinguishes CDA from motivational and executive models.

This new framing has implications across multiple domains:

- Clinical Psychology: Slip provides a structural explanation for volitional breakdowns often misinterpreted as attention disorders or emotional dysregulation. CDA offers a non-pathologizing model grounded in system alignment.

- Education: Teachers and instructional designers can use CDA to differentiate between motivational problems and structural engagement failures, tailoring interventions accordingly.

- Human–Computer Interaction (HCI): Adaptive systems can detect high-Slip states through behavioral or physiological proxies and dynamically scaffold user engagement.

- Self-Regulation and Coaching: Individuals can use CDA to track internal misalignments, adjusting routines or environments without self-blame.

Crucially, CDA offers a non-deficit model of effort variability. Scattered days and inconsistent performance are not viewed as personal shortcomings, but as structurally coherent signals within a complex system.

“You don’t need to fix it right away. You just need to notice the structure shifting and adjust gently” (Lagun, 2025, p. 27).

As a proposed new field within cognitive psychology, Cognitive Drive Architecture does not seek to replace existing theories of motivation, executive function, or behavioral economics. Instead, it provides a host structure that defines when and how these other systems can operate effectively. Lagunian Dynamics, as its foundational theory, introduces a mathematically defined and empirically testable model for Drive—offering a systematic language for understanding the variability that conventional models treat as noise.

By naming and structurally defining phenomena like Slip, CDA reframes inconsistency not as a failure to overcome, but as a feature to understand. In doing so, it opens new pathways for diagnostics, adaptation, and cognitive design in the study and support of effort.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.