There's No Such Thing as a Realistic Photo

Is Photography Always Truthful?

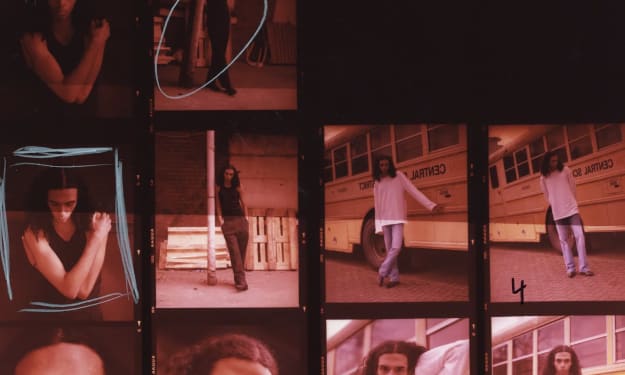

Working with film photography (and, especially, posting said film photography on the Internet), you’re met with many responses that measure your photography's validity with their obsession with realism.

There seems to be almost a spectrum.

On one end of the spectrum, you have what is deemed “realistic”. It’s what you should strive for if you’re a serious photographer. This is the same realism that indicates whether or not a film stock should be highly regarded. Kodak Portra 400 is the holy grail. Lomography Metropolis, on the other hand — who even shoots that? (Spoiler: I do.)

The other end of the spectrum is for the true creative geniuses. This end rewards the ultra-unrealistic. The photos are playful in their representation of colour and lighting, which borders on surrealism. This is what you strive for if you’re a talented artist at the height of creativity.

When you slightly miss the mark at either end of this spectrum, you’re reminded that your photos, your scans, your prints, aren’t realistic enough, so they can’t be good enough.

I’ve been thinking a lot about this as of late because I’ve been met with those same comments for years. It comes with the territory when you’re a photographer who also posts your work on YouTube (and don’t get me started on Reddit).

Recently, I made a video that discussed how I edit my digital photos to create consistency throughout my portfolio between what I shoot that is digital and what I shoot that is film. Of course, if you have the words “edit” and “digital” anywhere near the word “film”, you’re inviting hoards of comments that tell you why you shouldn’t edit like film — or, why you can’t edit like film — even though they’ve not watched the video and, if they have, they’ve entirely missed the point.

This week, one of the conversations in my comment section was focused around the idea of film photographers of the past using film stocks that centred their work around “colour accuracy” and it had me thinking a lot about what this means, and whether it’s something that can even be achieved in a subjective world.

I’ve always felt as though subjectivity in art is fact. Surely, we know by now that art is indeed subjective. There is not one way to do it, and there is certainly not one way to do it that everyone will enjoy.

Beauty Is In The Eye of the Beholder

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder was coined by Molly Bawn back in 1876. For at least the last 149 years, this idea of subjectivity has been thrown around.

Yesterday, we had a spell of good weather. It’s a novelty in Manchester, and so, to the park I went. I was sunbathing on my back for a good twenty minutes, and when I opened my eyes and looked around, everything was colder. It’s like the yellows in the world had been lifted. The green grass was less saturated, and the skin tones of the other park-goers were almost more lifeless. This lasted, of course, for only a few minutes before my “normal” vision returned, but I think it’s proof of what we already know: people don’t see the world in the same way.

It’s the beauty of photography - of art in general - that we don’t see the world the same as one another. It’s why some people can make photos out of things you would walk past, and why you stop and stare at the things that others don’t care for. It’s why some people will hold artists on a pedestal as the best of a generation, or even the best of all time, but you don’t share the same emotion.

Art without subjectivity is science.

When I was at school, I had a form tutor who I couldn’t stand, but one thing that he successfully did was engage our class in a conversation about individualism. He didn’t coin the concept, but he was the first to describe it to me in a way that I understood or wanted to think more about. It was the idea that everyone could see colours differently, and that that’s something we’ll never truly know. I might see red in the way that you see green, but we’ve both been taught to label it as “red”. I could describe red to you as bright, as warm, as powerful, but you might have been taught that the colour green (as I see it) can be described by all of those words too, and so a conversation between the two of us will never truly get to the truth of whether we see colours in the same way. Of course, there is the science of colour and light and wavelengths to consider, but let’s put that aside for a moment and focus on the possibility that maybe, just maybe, you and I see the world entirely differently.

The Camera Always Lies

I went to a talk with Martin Parr earlier this year. Recently, I’ve become enamoured with the art of street photography and Martin Parr, to me, is one of the greats.

Within his talk, he showed two photos that he took of a tree at night, during bad weather. Both images were black and white, both images were taken from the same vantage point and of the same subject, but for the first photo, he used a flash, and for the second, he didn’t. Within the flash photo, the rain/snow was illuminated by the flash, and the whole image had an air of surrealism to it. Within the photo without flash, you couldn’t tell there was bad weather at all.

He explained how this was a lesson in photography not being a great indicator of the truth. If you wanted to tell the story of the weather, the flash did that perfectly, but you could choose to tell the story without mentioning the weather at all. Suddenly, the story has changed.

If we can use a camera to bend the truth, and that is a part of the art, a part of the storytelling, that comes with being a photographer, is realism something that we should have to strive for?

The Internet & Its Entitlement to Other People’s Art

One of my gripes with the Internet, and the world in general, is that we don’t allow people the freedom to engage with their lives in the way that they want to. We must have an opinion.

There is an entitlement to other people’s art that exists. We must tell people the right or wrong way to do things, to take a photo, to use a paintbrush, to write a story. The Internet has become a sounding board for these types of comments or narratives. It’s created a culture of superiority and, quite frankly, is the reason that many people are afraid to share their work with the world, in fear of unsolicited “constructive” criticism and outright rude remarks.

It’s not the first time I’ve spoken about my distaste for this, and I can almost guarantee you it won’t be the last, but it’s an interesting study on human behaviour nevertheless. In a world where we know art is subjective, why are we so intent on telling people there’s a right way to do it?

This is a roundabout way of me saying, I don’t truly believe that there’s such a thing as a realistic photo. If everyone’s perception of reality is different, how can there be? That said, striving for your work to match your understanding of reality, your perception of beauty, your grasp on the world, is not a bad thing. Engage in your art without thinking at all, or by thinking a whole lot. Simply, engage in your art in a way that feels right to you.

About the Creator

Sophia Carey

Photographer and designer from London, living in Manchester.

sophiacarey.co.uk

Comments (2)

I think it’s a really interesting point that we all ‘see’ things differently. Love your photos - especially the train and the lone raver. Excellent.

Nice