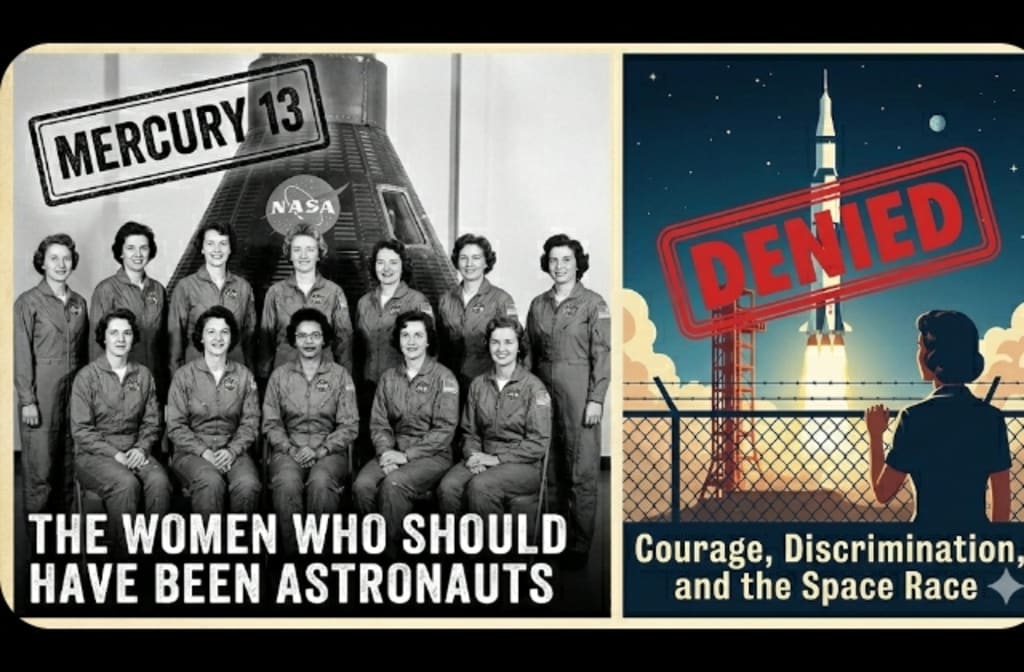

The Wrong Stuff: The Untold Story of the Mercury 13 and the Dreams That Were Grounded by Bias

In the shadow of the Space Race, thirteen extraordinary women proved they were physically and mentally equal to America’s male astronauts. History, however, wasn't ready to believe them

When we look back at the grainy, triumphant footage of the early 1960s Space Race, the imagery is deeply embedded in the American psyche. We see towering rockets capped with tiny silver capsules, Mission Control centers filled with chain-smoking men in white shirts and skinny ties, and, of course, the astronauts themselves. They were the embodiment of mid-century masculine heroism: fighter jocks with buzzcuts and iron jaws, possessing what author Tom Wolfe famously dubbed "The Right Stuff." They were Alan Shepard, John Glenn, and Gus Grissom—names etched into history books as the pioneers who rode fire into the heavens to beat the Soviet Union.

Yet, just outside the frame of that carefully curated historical narrative, a parallel reality existed. It is a story that remained largely hidden for decades, a painful testament to how prejudice can override scientific data and national interest. It is the story of thirteen women who were just as qualified, just as brave, and just as ready to launch as their male counterparts, but who were grounded not by gravity, but by the immovable cultural barriers of their time. They are known today as the Mercury 13.

To understand the magnitude of their story, we must first understand the atmosphere of the era. The dawn of the 1960s was characterized by a terrifying geopolitical anxiety. The Cold War was at its peak, and space was its newest battleground. The Soviet Union was pulling ahead, stunning the world with Sputnik and then putting Yuri Gagarin into orbit. America was desperate to catch up, to prove that democracy could out-innovate and out-perform communism on the ultimate frontier.

In this high-stakes environment, NASA’s criteria for selecting the first human spaceflight candidates—the Mercury 7—were rigid. President Eisenhower insisted that astronauts be drawn from the ranks of military test pilots. It seemed like a logical requirement; these were men accustomed to life-or-death situations in experimental high-speed aircraft. However, this requirement served another, unspoken function: it acted as a foolproof filter against women. In the 1960s, women were categorically barred from becoming military jet test pilots. By setting this single criterion, NASA effectively hung a "Men Only" sign on the gangway to the stars, without ever having to explicitly state that gender was a factor.

Not everyone accepted this status quo. Dr. William Randolph "Randy" Lovelace II was a pioneering physician and an aerospace medicine specialist. He had been instrumental in developing the grueling physical and psychological battery of tests used to select NASA's male astronauts. Lovelace was a man of science, driven by data rather than dogma, and he harbored a radical curiosity: if you stripped away the social assumptions, were women physically capable of handling the rigors of spaceflight?

Lovelace suspected they might be. He theorized that women’s typically smaller frames would require less oxygen and food, a significant advantage in the cramped confines of a space capsule where every ounce mattered. Furthermore, some research suggested women might possess higher tolerance for pain and certain types of physiological stress. NASA, bound by its military pilot rule, wasn't interested in investigating this. So, Lovelace decided to find out for himself.

Using private funding, outside the official auspices of the government space program, Lovelace launched the "Woman in Space Program" at his clinic in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He intended to subject female pilots to the exact same physical and psychological torture chamber he had designed for the men.

He didn't have to look far for his first volunteer. Geraldyn "Jerrie" Cobb was an aviation prodigy. By 1960, she was already an exceptionally accomplished pilot, holding multiple world aviation records for speed, distance, and altitude. She had logged thousands of hours in the cockpit—significantly more, in fact, than several of the men who became household names as Mercury astronauts. Cobb was fierce, focused, and desperate to fly in space.

Jerrie Cobb arrived at the Lovelace Clinic in February 1960. What followed was a week of relentless, invasive examination designed to find any possible breaking point in the human body and psyche.

The testing regimen was the stuff of nightmares. The candidates had tubes inserted into their stomachs to test gastric juices. They were subjected to tilt-table tests to measure circulation efficiency under duress. They had ice water injected directly into their ears to induce vertigo, simulating the disorientation of a tumbling spacecraft, measuring how quickly they could regain control. They were placed in compression chambers to simulate high-altitude depressurization.

Cobb didn't just survive the gauntlet; she thrived in it. Her results were stellar, mirroring and in some cases exceeding the benchmarks set by the male Mercury candidates.

Encouraged by Cobb's performance, Lovelace expanded the program, recruiting more high-profile female pilots. By the end of 1961, twenty-five women had undergone the testing. Thirteen of them passed with flying colors.

The group that would eventually be christened the "Mercury 13" were not dilettantes or hobbyists. They were seasoned professionals, engineers, and mothers who shared a profound love for aviation. They included women like Wally Funk, the youngest of the group at just twenty-one. Funk was a force of nature, possessing an irrepressible spirit. During one phase of testing, candidates were placed in sensory deprivation tanks—floating in dark, soundproof, body-temperature water to test their psychological resilience against isolation. The absolute limit of human endurance was thought to be six hours. Wally Funk remained in the tank for over ten hours, eventually emerging only because the doctors ended the test. She hadn't cracked; she had simply taken a nap.

Then there was Jane “Janey” Briggs Hart, a mother of eight, a licensed helicopter pilot, and the wife of a U.S. Senator. There was Sarah Gorelick, an electrical engineer and mathematician who raced airplanes. These were women who had already spent their lives pushing against the boundaries of what society said they should be doing.

For a brief, shining moment, it seemed possible. The data was irrefutable: these thirteen women possessed the physical and mental fortitude required for space travel. Jerrie Cobb, serving as the group’s unofficial leader, began lobbying in Washington, trying to gain official recognition for the program. There were murmurs of a conjugal space flight, or perhaps an all-female mission.

But the moment the program threatened to move from a private medical experiment to an actual operational reality involving government resources, the door slammed shut with ferocious speed.

The next phase of testing was scheduled to take place at the Naval School of Aviation Medicine in Pensacola, Florida, involving advanced equipment like centrifuges and ejection seat simulators. But just days before the women were set to arrive, the Navy abruptly canceled their use of the facilities. Without an official directive from NASA, the military would not cooperate. Lovelace’s private funding could only go so far.

The program was dead in the water.

Jerrie Cobb and Janey Hart refused to let the dream die quietly. In July 1962, they traveled to Washington D.C. to testify before a special Subcommittee of the House Committee on Science and Astronautics. They were there to argue that excluding women based on a lack of military jet training—training they were legally forbidden from acquiring—was discriminatory and short-sighted.

The hearings were a study in dismissal. The women were met with condescension and polite indifference from lawmakers. The nail in the coffin came from NASA representatives and, painfully, from John Glenn himself. Fresh off his historic orbital flight, Glenn was an American demigod at that moment. His testimony carried immense weight. He told the committee that while he wasn't against women in space, the fact that they weren't currently in the program was just a reflection of the "social order" of the country. He argued that testing women would be a distraction from the primary goal of beating the Russians to the moon.

The message was clear: The data didn't matter. The fact that Wally Funk could outlast men in sensory deprivation didn't matter. The fact that Jerrie Cobb had more flight experience didn't matter. The "social order" demanded that space heroes look a certain way, and that way was male. The subcommittee found no discrimination in NASA’s policies. The Mercury 13 were told to go home.

The bitterest pill came just a year later. In June 1963, the Soviet Union stunned the world again by launching Valentina Tereshkova into orbit. She was not a military test pilot; she was a textile factory worker and an amateur parachutist before being selected. The Soviets saw the propaganda value in sending a woman to space and simply made it happen.

The United States could have easily beaten them to this milestone. The Mercury 13 were ready years before Tereshkova launched. America missed a vital opportunity to demonstrate equality on the world stage because it couldn't overcome its own internal biases.

It would take another twenty years for the United States to catch up. When Sally Ride finally became the first American woman in space aboard the Space Shuttle Challenger in 1983, the rules had changed. The pilot requirement had been relaxed for "Mission Specialists," allowing scientists and engineers into the corps. The cultural tide had shifted, thanks in part to the groundwork laid by the feminist movements of the 60s and 70s.

The members of the Mercury 13 watched Sally Ride’s launch from the sidelines. For them, it was a moment of complex emotions—immense pride in seeing that glass ceiling finally shatter, mixed with the profound personal grief of knowing it should have been one of them decades earlier. They had been the right people at the wrong time.

For decades, their story remained a footnote, known only to space historians and feminist scholars. It wasn't until the 1990s, when the term "Mercury 13" was coined, that their narrative began to gain traction in documentaries and books. They started receiving the recognition they deserved, not as failed astronauts, but as pioneers who exposed the arbitrary nature of systemic barriers.

In a beautiful, poetic coda to their saga, Wally Funk finally got her due. In July 2021, at the age of 82, the woman who had set records in the sensory deprivation tank six decades earlier blasted off aboard Blue Origin’s New Shepard rocket. She became, for a time, the oldest person ever to fly to space, fulfilling a lifelong dream and carrying the spirit of the other twelve with her.

The story of the Mercury 13 is more than just a dusty chapter of aerospace history. It is a vital, resonant American narrative about courage, discrimination, and the immense cost of prejudice. It forces us to confront an uncomfortable question: how many breakthroughs, how many innovations, and how much progress have we lost throughout history simply because we refused to let capable people walk through the door because of what they looked like, or who they were?

These thirteen women exemplified grit and brilliance at a time when their dreams were dismissed not for lack of talent, but because of outdated assumptions. They proved that having "the right stuff" wasn't about gender; it was about skill, resilience, and the burning desire to explore the unknown. Their legacy isn't recorded in flight logs or mission patches from the 1960s, but in the careers of every female astronaut, aviator, and engineer who followed in the slipstream they created by refusing to take "no" for an answer. They are a powerful reminder that sometimes, the most important pioneers are the ones who fight the battles on the ground so that others may eventually touch the stars.

About the Creator

Frank Massey

Tech, AI, and social media writer with a passion for storytelling. I turn complex trends into engaging, relatable content. Exploring the future, one story at a time

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.