The Real MVP: Text Mining the Book of Job in the Bible

Applying Computational Text Analysis Techniques to the Book of Job

I. Abstract

This study applies text mining techniques to the entire Book of Job, utilizing word frequency analysis, sentiment analysis, and topic modeling to uncover hidden patterns and insights within the text. The Book of Job, a profound exploration of suffering, divine justice, and the human condition, has long been a subject of theological and literary interpretation. Using computational methods, this study examines the overall linguistic features of the text, identifying significant word frequencies and their contextual implications. Findings from the word frequency analysis highlight recurring themes and motifs, while the sentiment analysis indicates a slightly negative emotional tone, reflecting the pervasive despair in Job's narrative. The topic modeling results provide additional insight into the key thematic clusters, shedding light on the interplay between divine justice, human suffering, and existential questioning throughout the text. This analysis offers a fresh, data-driven perspective on the Book of Job, enriching our understanding of its complex narrative structure and themes.

II. Introduction

The Book of Job, part of the Hebrew Bible’s Ketuvim (Writings), is traditionally dated to around the 6th century BCE, though its exact origin remains debated. It is considered one of the earliest and most sophisticated examples of biblical wisdom literature, tackling profound questions about suffering, justice, and the nature of God. Job, a righteous man, is subjected to intense suffering as part of a divine test, sparking a series of dialogues with his friends and culminating in a direct encounter with God. The book's central theme revolves around the paradox of divine justice in the face of innocent suffering.

In the narrative, Job loses his wealth, health, and family, and his friends argue that his suffering is a punishment for sin. Job rejects their accusations, demanding an explanation from God, who ultimately responds with a display of divine power and wisdom. Job’s ultimate restoration reinforces the idea that divine purposes often transcend human understanding.

The Book of Job has had a profound impact on Christian theology and culture, shaping discussions about theodicy—the justification of God’s goodness despite the existence of evil. Its themes of suffering, faith, and the mysterious nature of God's will have been explored in countless theological works, sermons, and art. Job’s story has been used to explore the relationship between human suffering and divine providence, influencing Christian perspectives on patience, perseverance, and the limits of human understanding in the face of divine mystery.

The Book of Job is often interpreted through various lenses, emphasizing its complex portrayal of suffering, justice, and divine-human relationships. In The Meanings of the Book of Job (2018), Michael V. Fox challenges the conventional view that Job refutes retributory theology, arguing instead that the book teaches divine justice, though imperfect and incomplete. Fox contends that while God values justice, other concerns can override it, and the book encourages human loyalty even in the face of injustice. Importantly, Fox asserts that God does not terrify Job in the theophany but engages him in a rhetorical dialogue that underscores human dignity and the need for human cooperation in the divine plan (Fox, 2018).

In Becoming Wise (1991), Achenbaum and Orwoll offer a psycho-gerontological reading, suggesting that Job’s journey represents the transformation involved in gaining wisdom. Wisdom is portrayed as a dynamic, integrative process involving personality, cognition, and conation. They argue that Job’s struggle to understand his suffering highlights gender-specific challenges and the role of mourning, with Job's eventual wisdom emerging through his confrontation with loss and the failure of traditional consolation (Achenbaum & Orwoll, 1991).

Finally, in The Book of Job in Ritual Perspective (2015), David A. Lambert explores Job’s narrative within the framework of ritual mourning. He proposes that Job’s suffering and protest reflect a ritualized process of mourning, offering a new perspective on the unity of the text. This analysis touches on biblical themes of national mourning and highlights the implications of Job's story for broader theological and canonical considerations (Lambert, 2015).

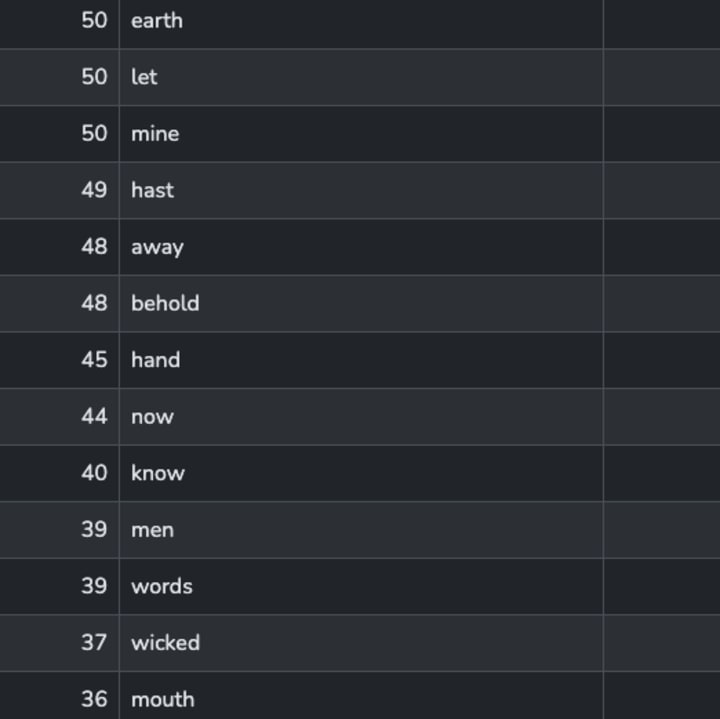

III. Word Frequency Analysis of the Book of Job

*Stop words were removed (ie. job, god, shall).

The words earth, mine, behold, hand, and now appear to stand out as words that can give readers some deeper insights into hidden patterns in the Book of Job. Toggling was used to examine how each of these five words were being used within their respective contexts.

The word "earth" appears 50 times in the text and only refers to the stage in which the events transpiring in the text are occurring. The word "earth" is not used in a way to describe dirt or soil, etc. Also, though the word "earth" appears 50 times in the text, further insights can be gained by specifically examining the first two uses of the word "earth".

Chapter 1 (Verse 7) reads "And the LORD said unto Satan, Whence comest thou? Then Satan answered the LORD, and said, From going to and fro in the earth, and from walking up and down in it.

Chapter 1 (Verse 8) And the LORD said unto Satan, Hast thou considered my servant Job, that there is none like him in the earth, a perfect and an upright man, one that feareth God, and escheweth evil?

These two verse are interesting because it can be argued that God is taunting Satan because if Satan had be wondering all over the Earth, how had he not attacked Job alread if "there is non like him in the earth". These verses also may encourage readers to ask the question, "Is Satan responsible for all of the bad things that happen to people, or does God also participate in inflicting suffering on people, or are they both involved".

Moving on, the word "mine" appears 50 times in the text. It is being in the same way that we use the word "my" today. Job is very considered with his body, body, soul, and his general circumstances. Though some have argued that Job was possibily selfish and only served God for material gain and fear of punishment (the same argument Satan made in the first versus of the text), these arguments seem weak given that the word "God" is used 126 times in the text and the word "lord" is mentioned 33 times in the text , these arguments don't seem so sound.

Next, the word "behold" appears 48 times in the text. This word could have possibly been a stop word given that it is an interjection that basically mean "look man", "pay attention", or even "check this out" today. It would be interesting to see someone do a correlation analysis on the words that correlate with the word "behold" and unravel any hidden insights.

Next, the word "hand" appears 45 times in the text. Toggling revealed diverse usages of the word. Clapping hands, God's hands, and possession all characterize the word's usage. Overall, a reader may see the word "hand" as a reference to power and praise. The hands also seem linked with work. Readers may begin to even think about the natural science of human hands. The hands really are the primary physical extensions of the body, the first way in which we manipulate our environments, and in God's case, how he controls his creation. Perhaps the word hand is very frequently used in the entire Bible. This would be an intersting topic for further study.

Finally, in regard to this word frequency analysis, the word "now" appears 44 times in the text. After toggling, it appears the word now was overemphasized in the text because of its use in the word "know," so this word is less significant. Also, an close reading of the text reveals that it is being used as a transition word that should probably classified as a stop word not worth exploring. To compensate for this miscategorization, the word "wicked", which occurs 37 times in the text, was explored. Toggling revealed a particularly interesting passage that seems to characterize the words overall usage in the text.

Chapter 10 (Verse 15) If I be wicked, woe unto me; and if I be righteous, yet will I not lift up my head. I am full of confusion; therefore see thou mine affliction; 10:16 For it increaseth. Thou huntest me as a fierce lion: and again thou shewest thyself marvellous upon me.

This verse does appear to represent the overall usage of the word wicked, and also gets at the heart of the entire Book of Job. Why would God punish a righteous man, via Satan, and not a wicked person. Job may subconsciously feel wicked. In many ways, Job is questioning his own intelligence in relation to God. Unlike readers, Job does not know that God allowed Satan to attack him.

IV. Sentiment Analysis

The sentiment analysis of the text from paste.txt has been completed successfully. The results indicate a polarity score of -0.11, suggesting a slightly negative sentiment, and a subjectivity score of 0.55, indicating moderate subjectivity.

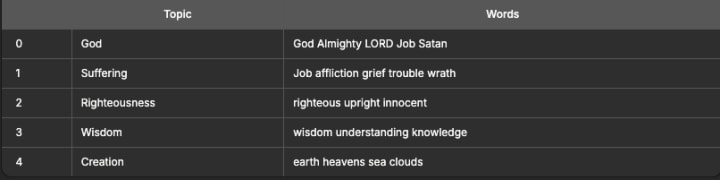

V. Topic Model

VII. Conclusion

This study demonstrates the value of text mining techniques in offering new perspectives on the Book of Job. By analyzing the entire text, we were able to identify linguistic patterns and thematic trends that reflect the central concerns of the narrative, such as suffering, divine justice, and the human struggle for understanding. The word frequency analysis revealed recurring motifs that emphasize the text's focus on cosmic events and personal affliction. Sentiment analysis showed a predominantly negative tone, aligning with Job's despair and confusion throughout the story. The topic modeling further clarified the key thematic clusters of the book, linking concepts like divine power, righteousness, and existential suffering. This computational approach not only deepens our understanding of the Book of Job but also highlights the potential of text mining as an interdisciplinary tool for analyzing ancient religious and literary works. Future studies could expand on this analysis by exploring correlations between key terms or applying more sophisticated modeling techniques to further unpack the narrative's complexities.

About the Creator

T.J. Greer

B.A., Biology, Emory University. MBA, Western Governors Univ., PhD in Business at Colorado Tech (27'). I also have credentials from Harvard Univ, the University of Cambridge (UK), Princeton Univ., and the Department of Homeland Security.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.