The Bureaucrat of Rome: How One Man’s "Incompetence" Saved the Eternal City

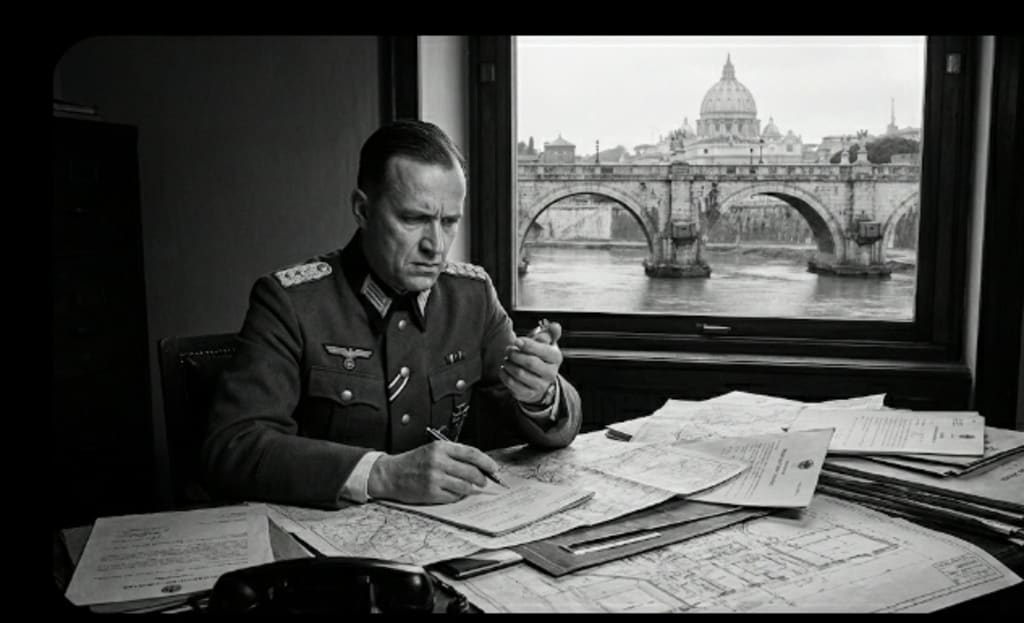

In the final days of WWII, the Nazis planned to blow up Rome’s bridges and historic landmarks. Major Gerhard Wolf, a German engineer, stopped them without firing a shot. His weapon? Paperwork

The incredible true story of Major Gerhard Wolf, the German officer who quietly sabotaged Nazi plans to destroy Rome by using delays, bureaucracy, and "incompetence" as a weapon.

Rome, 1944. The Eternal City was holding its breath.

The war was entering its final, most chaotic phase. The Allies were pushing north through Italy. The German army was preparing to retreat, but they had one final, devastating order from Berlin: Leave nothing behind.

The strategy was called "scorched earth." The goal was to cripple the advancing Allied army by destroying infrastructure. But in a city like Rome, "infrastructure" meant history. It meant the Ponte Sant'Angelo, the ancient bridges across the Tiber, the aqueducts, the power plants, the very arteries of a city that had stood for two millennia.

The explosives were in place. The fuses were wired. The demolition schedule was set. It was a military operation, precise and inevitable.

The man in charge of the logistics for the German command in Rome was Colonel Dietrich von Choltitz. But the man on the ground, the engineer responsible for the technical execution of the destruction, was a subordinate officer named Major Gerhard Wolf.

Gerhard Wolf was not a hero in the cinematic sense. He was not a resistance fighter. He was a career soldier, a bureaucrat, a man who understood supply chains, timetables, and engineering schematics. He was a cog in the machine of the Third Reich.

But Wolf had a problem. He loved Rome.

He was an educated man, a lover of art and history. He had spent his time in the city not just as an occupier, but as an admirer. He understood that what he was being asked to destroy wasn't just strategic infrastructure. It was the cradle of Western civilization.

He faced the ultimate moral dilemma of a soldier in a criminal regime.

Option A: Obey orders. Be efficient. Do your job. The result would be the destruction of thousands of years of history and the crippling of a city of millions.

Option B: Disobey orders. Sabotage the mission. The result would be a court-martial, a firing squad, or a hangman's noose.

Wolf realized that open rebellion was suicide. If he stood up and refused, he would be executed within the hour, and someone else would push the plunger.

So, he chose a third option. A quieter, more dangerous option.

He decided to become incompetent.

Evil, Wolf realized, often depends on efficiency. The Nazi war machine was terrifying because it was organized. It relied on speed, clear communication, and the seamless execution of orders. If you could disrupt that efficiency, you could disrupt the evil.

Wolf became an artist of obstruction.

When the orders came down to begin the demolition sequence for the bridges, Wolf didn't say no. Instead, he requested clarification. He sent memos asking about the exact type of explosives to be used, citing concerns about the structural stability of adjacent buildings. He demanded new calculations.

He "lost" critical paperwork. Approval forms for the final detonation orders would mysteriously vanish from his desk, only to reappear days later, misfiled in the wrong folder.

He created logistical nightmares. He would order the transport trucks moving the detonators to take circuitous routes, citing "partisan activity" on the main roads. The trucks would arrive hours late.

He used the bureaucracy against itself. The German army was obsessed with protocol. Wolf weaponized that obsession. He would refuse to sign off on destruction orders until every single box was checked, every regulation followed to the letter.

He became the living embodiment of red tape.

He was walking a terrifying tightwire. His superiors were furious. They screamed at him. They threatened him. They accused him of incompetence, of cowardice.

But they couldn't prove it was sabotage. Wolf always had a plausible, bureaucratic excuse. “The forms were not in triplicate, Herr Oberst. I could not proceed.”

Meanwhile, he was playing a double game. He secretly met with Vatican officials and representatives of the Italian resistance. He quietly fed them information about which buildings were rigged, which timelines were firm, and where the weak points in the German plan were.

He used his position to delay the inevitable, buying time for the Allies to arrive, buying time for the resistance to disarm the explosives.

The tension in those final days was unbearable. The Allies were closing in. The German command was frantic. The pressure on Wolf to "just push the button" was immense.

But he held the line. He kept stalling. He kept "fumbling."

On June 4, 1944, American troops entered Rome.

The bridges across the Tiber were still standing. The historic center was largely intact. The power plants were not destroyed.

The German army retreated, leaving behind a city that had been saved not by a grand battle, but by a thousand tiny acts of deliberate inefficiency.

Gerhard Wolf was captured by the Allies. He was interned as a prisoner of war. After the war, he returned to Germany and lived a quiet life. He rarely spoke about what he had done.

He didn't receive medals. He didn't get a parade. For decades, his role in saving Rome was largely unknown, overshadowed by the larger dramas of the war.

But the people of Rome knew. In 1995, a plaque was dedicated to him on the Ponte Sant'Angelo. It doesn't call him a hero. It calls him a "friend of Rome."

Gerhard Wolf’s story is a powerful reminder that resistance doesn't always look like a man with a gun. Sometimes, it looks like a man with a clipboard, slowly shuffling papers, refusing to be efficient in the service of destruction.

It challenges us to rethink what courage looks like inside a toxic system. We often think we have to burn the system down to change it. Wolf showed that sometimes, the most effective way to fight is to simply jam the gears.

He proved that when the world demands speed in the wrong direction, the most revolutionary act is to slow down. He proved that one man, armed only with the courage to be "incompetent," can save a city.

About the Creator

Frank Massey

Tech, AI, and social media writer with a passion for storytelling. I turn complex trends into engaging, relatable content. Exploring the future, one story at a time

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.