Researchers find a novel organelle in human cells that could have a significant effect on health.

This other pathway could explain MVB formation that is not addressed by conventional ideas.

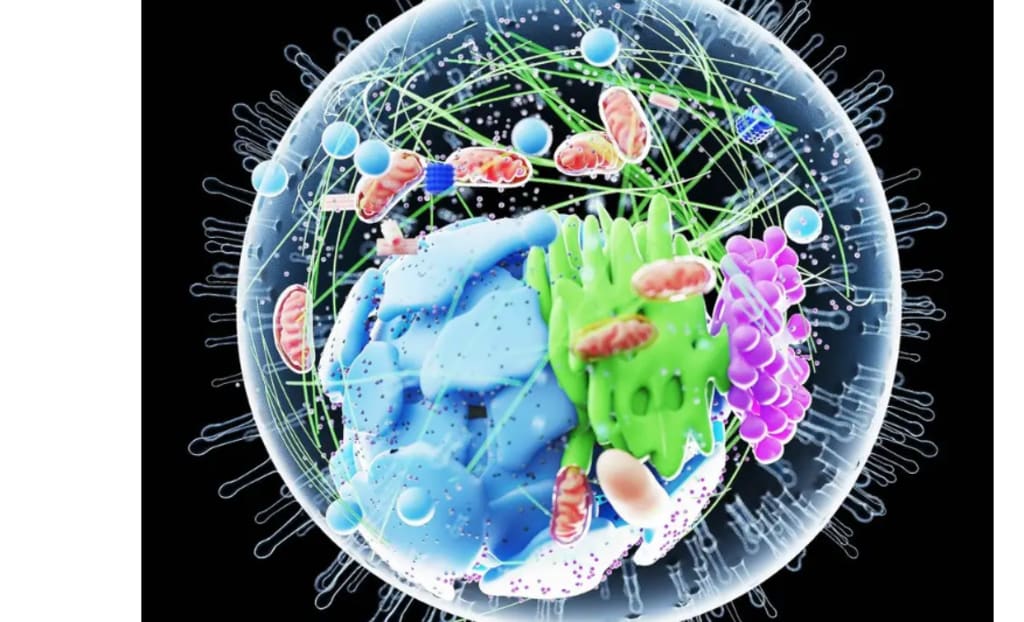

The field of cell biology is one of hidden structures and perpetual motion. Decades of studies with microscopes, stains, and models have given us a great deal of knowledge about cells. However, surprises still arise in this well-traveled area—enter the "hemifusome."

How cells sift, recycle, and dispose of their internal cargo may be explained by this hitherto unidentified organelle. Life depends on this function, which is frequently interfered with in cases of hereditary illness.

Scientists from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the University of Virginia discovered this organelle, which provides a unique perspective on how the cell functions.

It also offers a potential paradigm shift in our knowledge of illnesses when cellular housekeeping fails. Researchers have captured this organelle in action using state-of-the-art imaging techniques and described its possible implications for medicine and health.

This is the hemifusome.

The hemifusome is a transient structure that emerges and vanishes in response to the demands of the cell rather than being a permanent part. It is made up of two vesicles connected by a hemifusion diaphragm, a partial membrane connection.

Because of their shared boundary, the vesicles in this configuration are able to interact without completely merging. According to researcher Seham Ebrahim, Ph.D., of UVA's Department of Molecular Physiology and Biological Physics, "this is like finding a new recycling centre inside the cell."

"We believe that the hemifusome aids in controlling how cells package and process materials, and when this isn't done correctly, it may lead to diseases that impact numerous bodily systems."

There are two ways that these hemifused vesicles can appear. While the flipped variant embeds the smaller vesicle on the inner, or luminal, side, the direct form attaches the smaller vesicle to the outer side of a bigger one.

A dense particle known as a proteolipid nanodroplet binds the structure at the junction in both situations, potentially directing its stability and development.

The appearance of the hemifusome

Researchers used cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) to investigate hemifusomes. Cells are quickly frozen using this imaging technique, maintaining them near their original state.

Cryo-ET gives researchers a true-to-life view of cellular architecture, unlike standard electron microscopy, which can destroy or distort fragile structures.

The team discovered hundreds of hemifusomes by looking at the periphery of four different mammalian cell types: COS-7, HeLa, RAT-1, and NIH/3T3. In those areas, these organelles accounted for almost 10% of all membrane-bound vesicles.

They appear to be common cellular components rather than uncommon aberrations based on their uniformity across cell types.

Ebrahim, of UVA's Centre for Membrane and Cell Physiology, described vesicles as "like little delivery trucks inside the cell." They connect and move cargo through the hemifusome, which functions similarly to a loading dock. We were unaware of this phase in the process.

Why the hemifusome is special

Hemifusomes are unique not just because of their shape but also because of their contents. Granular material, like that found in endosomes and ribosome-associated vesicles, is typically present in the larger vesicle.

The interior of the smaller vesicle, however, is smooth and translucent. This distinguishes it from other vesicles in the cell and probably indicates a protein-free or diluted water solution.

With a diameter of roughly 160 nanometres, the hemifusion diaphragm itself is remarkably enormous compared to the 10-nanometre diaphragms observed in typical vesicle fusion events. These long diaphragms seem steady rather than ephemeral, which suggests they might be long-lasting.

Dead-end hemifusion, a lens-like form in simulations, occurs when the diaphragm enlarges to the point where it swallows the entire smaller vesicle into the bilayer of the bigger one. The notion that such forms are only theoretical is called into question when this is observed in real cells.

The organelle's anchors and architects

The dense proteolipid nanodroplet, or PND, is a distinctive characteristic at the core of hemifusomes. These droplets are embedded at the edge of the hemifusion site and have a diameter of around 42 nanometres. Their protein and lipid composition raises the possibility that they could support or strengthen the hemifused structure.

Never previously have these PNDs been seen in such a capacity. Some are embedded in membranes, whereas others seem free in the cytoplasm. PNDs could be used as scaffolding to assemble new vesicles, according to researchers. The PND may initiate the production of the smaller vesicle found in hemifusomes as it integrates into a membrane.

This process differs from traditional vesicle fusion and is referred to as de novo vesiculogenesis. The absence of established docking processes and the existence of a distinct, translucent vesicle suggest that the hemifusome might assemble itself.

Are endosomes and hemifusomes related?

Hemifusomes are similar to certain endosomal structures in size and position. The researchers followed the path of gold nanoparticles, which are frequently used as markers to map endocytic activity, in order to look into this further.

The particles never showed up inside hemifusomes, but they did enter recognised endosomes and lysosomes. Hemifusomes may not be a part of the traditional endocytic process, based on this lack.

Rather, they might be a distinct system that functions without the help of proteins like ESCRT that sort cargo. This divergence could significantly affect our understanding of vesicle movement within cells.

Disease and multivesicular bodies

Hemifusomes can develop into increasingly intricate structures. Compound hemifusomes with several partially fused vesicles were seen in the study.

Multivesicular bodies (MVBs), which cells employ to decompose and recycle internal materials, may have been precursors to these.

ESCRT proteins create inward buds in the classical model, which finally pinch off inside a bigger vesicle. However, vesicles in hemifusomes expand with the aid of PNDs and develop inward by hemifusion.

This other pathway could explain MVB formation that is not addressed by conventional ideas.

This route is implicated in Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome. Defects in pigmentation, lung function, eyesight, and bleeding are characteristics of this hereditary condition. Problems with cellular recycling are at the heart of the illness. Future remedies and an explanation for these abnormalities may result from an understanding of the hemifusome.

A novel vesicle formation model

The findings suggest a complete paradigm in which PNDs cause translucent vesicles to develop, which then partially fuse with larger ones to form hemifusomes.

After that, these structures might develop into reversed hemifusomes by budging inward. They might eventually break out as free vesicles inside MVBs. Unlike the ESCRT system, which depends on precise protein coordination, this process is based on biophysical and structural cues.

Additionally, it avoids the requirement for significant lipid contributions from other organelles, resolving a long-standing conundrum in the study of vesicle formation.

"This is only the start," Ebrahim stated. Since hemifusomes are known to exist, we may begin to investigate their behaviour in normal cells and the consequences of malfunctions. We might develop fresh approaches to treating complicated genetic illnesses as a result.

What follows

This finding has far-reaching consequences that go well beyond cell biology. Decades of beliefs are challenged by the hemifusome, which provides a new method for how cells construct and control internal compartments.

It also encourages fresh perspectives on illness, particularly ailments in which cells are unable to control their waste. Future studies will concentrate on determining which proteins regulate the development of hemifusomes and the process by which PNDs are produced.

The existence of these structures outside of the cell's periphery is another question that scientists wish to answer. To address these issues, sophisticated imaging technologies and genetic models will be essential.

The hemifusome acts as a reminder in an area where many people thought the primary organelles were already mapped. Secrets remain in the cell. Additionally, some of them might

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.