It was a little black book of Life. I found it at an estate sale in an impoverished neighborhood, in a tattered cardboard box, jumbled together with a heap of rubbish and frayed, yellow folios of handwritten sheet music. A radiance emanated from its leather cover, seemingly iridescent amongst the refuse, and, from the moment I touched it, I knew it was precious—or, rather, had been meant to be precious.

I opened it. An inscription pasted to the front page read, “For my dear Robert—I hope this makes up for the past some—I love you, son—Theodore Devon.” The intimacy of the inscription, the unrefined eloquence of the script, and the intricate delicacy of the hand drawn fringe suggested to me a nature of such tender sensitivity that I was at once touched with a beautiful light of inspiration.

The situation of such an heirloom in its dubious state of careless, haphazard neglect only heightened my awe and provoked an impetus to action within me—I could not allow so personal and golden a relic to pass unheeded into the obscurity of an unmarked grave at the county landfill. I buried it again beneath the dusty cobwebs and parched reams of unheard symphonies, and carried my cardboard treasure chest to the little check-out table in the driveway, where it was given me, along with a contemptuous sneer, for five dollars, by Mr. Robert Devon himself.

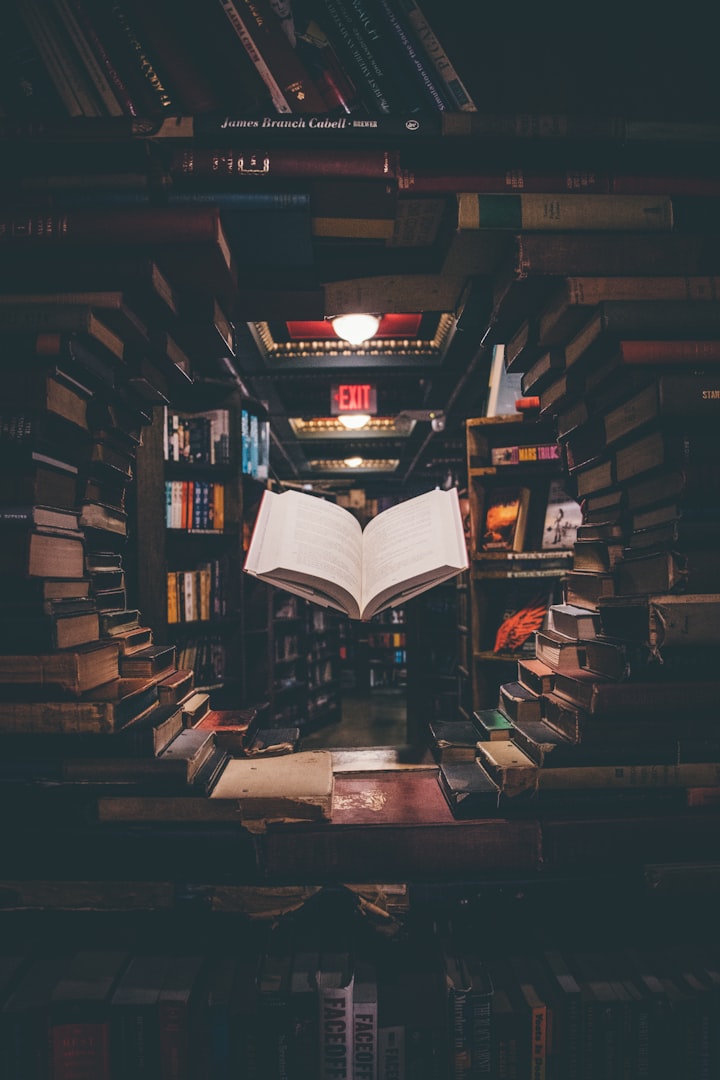

Arriving home I unearthed the tome immediately, with the excitement of an archaeologist who has just stumbled down a rabbit hole into ancient Lemuria. From the opening page it was an autobiography the likes of which I had never seen before, at once an address book and a memoir—a history, deeply personal, recollected through a series of vignettes. It was the scriptural reminiscence of the relationships of a mad man—not one mad in the sense of anger or insanity, yet mad as only a true philanthropist can and must be—to sacrifice so much for charity, to give so freely, not merely of one’s wealth, but of one’s self. It was the eulogy of a lover of humanity.

Theodore Devon had bankrupted himself through his pursuit of charity and an unprofitable passion for classical music. This financial poverty contributed to his eventual estrangement from his only son, Robert, who, after the death of his mother at an early age in a terrible house fire, suffered from a much more abject and insidious poverty of the spirit. As the distance between them grew, so did Theodore’s Apollonian commitment to music, and his Dionysian devotion to demonstrating the principals of compassion and lovingkindness with his own life, becoming an almost tragic obsession at times.

His kindness may very well have paid had Theodore been the type to accept payment—he held the keys of favor to many a locked door and sealed vault—yet he was not, and he descended into ever greater destitutions as the circle of the sun wound away its years. In the end he died alone in that slum where I found his book, hungry, cold, and penniless, yet with a legacy of love matched only by the most magnanimous of saints and martyrs. Though I believed Theodore left this earth happily, at peace with his ghost, one obvious and nagging regret remained—he had never been able to reconcile with his son.

On the final page, before a last heartrending imprecation to Robert for forgiveness and understanding, was an entry unique among the others—it was accompanied by no recollection, no anecdote nor explanation. It was only an address and a name—the name was Roger Little.

I arrived at Roger Little’s home in a wealthy district of town unannounced, and rang his doorbell with Theodore’s book in hand. The door opened momentarily and I was welcomed by the sound of a virtuoso violin spilling from another room, out and around a pretty, blonde, pregnant woman. The woman, was named Sophia, and she was Roger’s wife.

I took the liberty of introducing myself to her as a friend of Theodore Devon’s and expressed my great desire to speak with her husband. I saw the flicker of recognition in her eyes at the name of Devon, and she invited me to await in the hospitality of her kitchen while she approached her husband on my behalf. I sat at the kitchen counter and Sophia started a kettle of tea for me before going to speak with her husband. Presently, the music ceased and Roger entered the room, alone.

He was not a handsome man, being rather gangly and greasy haired, as musicians sometimes are. He had a pallid complexion and a rather waxy texture to his skin, with a certain hunting intensity dwelling around his eyes that often develops in one who has experienced hunger and desperation firsthand and has never quite adapted to the occurrence of plenty in their life. I laced my fingers and waited, and after a few moments of silent appraisal, it was Roger who spoke first.

“So, you knew Teddy. He’s gone?”

I spoke no answer, rather indicating the book where it lay upon the counter before me. Roger, taking it, sat at a table and began to read. He did not look up even as the kettle whistled and I poured our tea.

A long while we sat in silence as Roger read Theodore’s memoir—at times he laughed, at times he cried—our cups of tea were emptied, then refilled, then emptied again several times—and Roger never looked up. Finally, he finished the last page, and, with a sigh, closed the book.

“How did you get this?” he asked me.

“I found it, along with a bundle of sheet music in a cardboard box at an estate sale.”

Roger nodded, unsurprised, and handed me back the book. “I have read this, and that is enough. Thank you. But the music—the music—do you still have the music?”

I told him that I did, that it was in the box at my home.

“I am prepared to offer you one million dollars for every sheet of music in that box.”

“I will accept your offer, on one condition—the money is not to be paid to me, yet is to be used to fund a memorial concert of Theodore Devon’s music, in his honor, with you as soloist. The concert is to be conducted free of charge, and every person mentioned in this book is invited as a distinguished guest. Any remaining sum is used to establish a philanthropic Theodore Devon Musical Scholarship.”

“Done.”

It took several months to prepare and arrange the concert, but finally, on the 5th of February, the thirtieth anniversary of the house fire and the death of Theodore Devon’s wife, the music of Theodore Devon was performed live for the first time, in front of a packed house.

It was a gala. A celebration of life. There were tears and laughter— bright, pure love and gentle joy— savage sadness and raw passion. There was a vibrant, bubbling mirth, and a poignant, pressing loneliness. All was impressed and emphasized by the swelling rise and fall of the orchestra; all was pierced and bonded together by the catalytic trill of Roger Little’s violin.

As I walked about the VIP balcony, I saw the multitude from Theodore Devon’s little black book made flesh before me—faces soft or hard or somewhere in-between— smooth and clean, or dirty, pocked, and wrinkled—hands delicate and still, or calloused and quivering—lips trembling or smiling or even scowling—bodies draped in rags or jewels. The essences distilled into Theodore Devon’s black book filled the seats, undiluted, coming together to form something more than an assemblage of strangers—I saw them then, in that moment, connected, woven together with a string of music to form the web of a man’s life, of Theodore Devon’s life. Then, at the heart of the web, I noticed a hole, a vacant seat, with a placard still strung across its back which read “Reserved for Robert Devon.”

—and the portrait became complete.

—and the music ceased.

—and I knew Theodore Devon better than I ever could have had we spent a lifetime together.

And I wept.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.