Rethinking Justice and Revenge: Echoes from the Oresteia

How Aeschylus' Oresteia reveals the fragile boundary between justice, revenge and primal response

The stage opens with blood and ends with law. Aeschylus’ Oresteia, a trilogy of ancient Greek tragedies, charts a world suspended between the emotional and the institutional. At its heart lies a question that still haunts us: What is justice, and how does it differ from revenge? The plays present a cyclical, generational pattern of violence: Agamemnon sacrifices his daughter Iphigenia. His wife Clytemnestra murders him in return, and their son Orestes, in turn, kills her. Each act is a response to a prior harm, each justified by the language of duty, loyalty, and moral outrage. But then, something shifts. Athena intervenes, and the cycle halts. Not through more blood, but through judgment, argument, and law. What began as vengeance ends with justice, or so it seems. While the trilogy is often seen as a celebration of justice triumphing over revenge, a deeper reading reveals how both impulses share a common emotional and neurological origin. Drawing on philosophical insights from Plato and contemporary thinkers like Martha Nussbaum and Jonathan Haidt, as well as findings from neuroscience, the piece argues that justice and revenge are not opposites but reflections of the same human desire to restore moral balance. This article explores the fragile boundary between justice and revenge, using Aeschylus’ Oresteia as a philosophical lens.

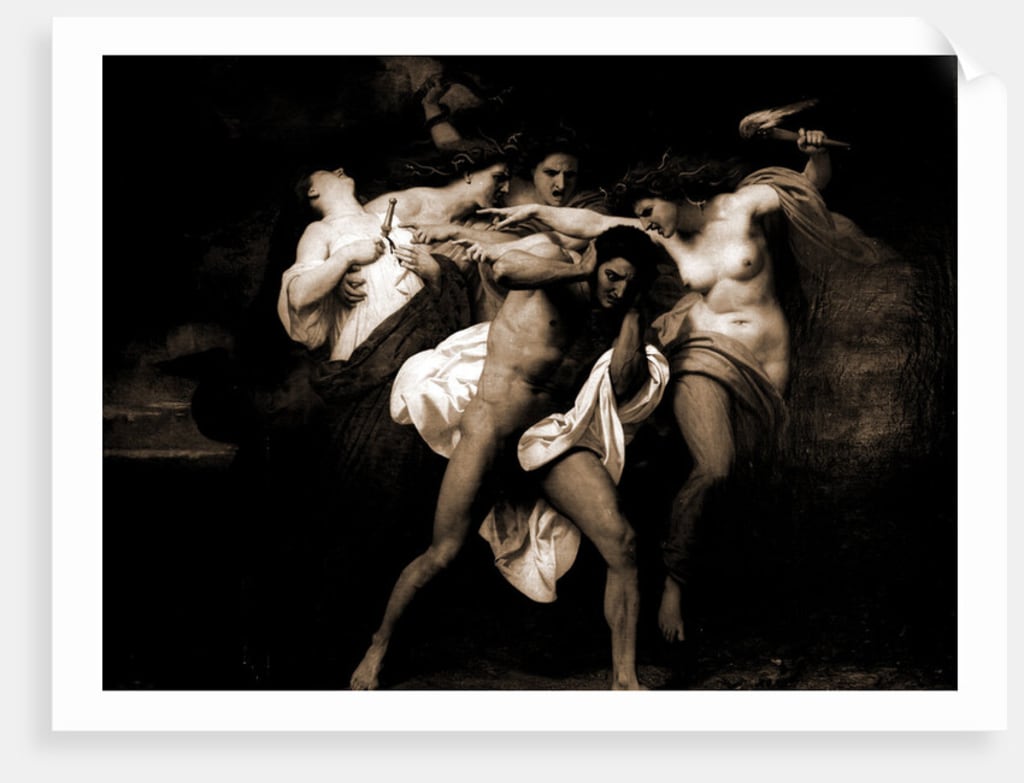

To understand the weight of this transition, we must first grasp the tragic spiral Aeschylus unfolds. The story begins before the curtain even rises: Agamemnon, commander of the Greek forces at Troy, faces a cruel dilemma. The gods demand the sacrifice of his daughter, Iphigenia, in order to grant winds for the ships. He obeys. This act, wrapped in political necessity and divine will, tears his family apart. When Agamemnon returns victorious from Troy, he is greeted not by celebration but by vengeance. Clytemnestra, his wife and Iphigenia’s mother, kills him coldly, not in a moment of passion, but in deliberate, calculated revenge. Her blade is not only a weapon—it is grief sharpened by time. But this, too, cannot stand. Orestes, their son, now grown, returns home. Torn between love and obligation, he heeds the voice of Apollo and slays his mother. The gods call it justice. But the Furies, the ancient spirits of retribution, rise to torment him.

The trilogy could have ended there, in an endless loop of pain repaid by pain. But it doesn’t. Athena, goddess of wisdom, steps in. She proposes not another act of retaliation, but a trial. Argument replaces wrath. Law replaces the knife. The Furies are not destroyed, but transformed into the Eumenides (the Kindly Ones), guardians not of vengeance, but of justice. The cycle, finally, is broken. And with this, the play declares the birth of civilisation: a shift from instinctual violence to structured judgment.

This resolution feels almost Platonic. In Plato’s Republic, justice is defined not as revenge or personal retribution, but as a harmonious order. Each part of the soul and each class of society performs its proper role. Justice, in this view, is an ideal Form: eternal, unchanging, and existing separately from the messy world of human impulse. Aeschylus seems to suggest something similar. The institution of the court is not simply a new tool, it’s a transformation of the very concept of right and wrong. Yet there is also a sophistic undertone to his message. Justice is not handed down by the gods anymore. It is debated, reasoned, and constructed by society. It is a human invention, forged in the crucible of conflict.

But is it truly that simple?

What Aeschylus stages for us is more than a mythic transition from chaos to order. It is a timeless reflection on the human urge to make things right, by any means necessary. In the Oresteia, revenge is not senseless. It is personal, yes, but it is also moral, emotional, and, in its own twisted way, logical. Orestes doesn’t kill out of hatred; he kills out of a sense of necessity, duty, and what he has been told is justice. Yet his act still drips with the same blood that marked his mother’s knife. This ambiguity is no accident. It speaks to something deeply human.

A Common Root: Primitive Reactions in a Complex World

The distinction between justice and revenge, I argue, is not natural. It is constructed. Neurologically, they arise from the same source: our primitive mechanisms of threat response, fear regulation, and moral intuition. Modern neuroscience shows that the same brain regions, the amygdala, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, and the anterior insula, are activated when people perceive unfairness or contemplate retribution (Greene & Haidt, 2002; Buckholtz & Marois, 2012). The emotional weight we attach to fairness and punishment isn’t learned in law school, it is evolutionary. It helped our ancestors survive in small tribes where betrayal and harm had to be punished swiftly to preserve group cohesion.

In this light, justice and revenge are not opposites, but variations of the same impulse: to restore a sense of equilibrium after harm. They are survival instincts, refined and repackaged by culture. Philosopher Martha Nussbaum reminds us that emotions are not irrational forces to be overcome, but intelligent responses to perceived values and threats. Psychologist Jonathan Haidt notes that our moral reasoning often follows emotional intuition, not the other way around. Justice, then, might be less about reason and more about ritualising rage.

This explains why we often feel conflicted. Why a court verdict might feel hollow. Why a revenge fantasy might feel disturbingly satisfying. Our minds, wired for survival, do not cleanly distinguish between institutional justice and personal vengeance.

The Role of Society, Family, and Experience

If the impulse is shared, what separates the two is how we are taught to act on it.

Our families, cultures, and early experiences frame how we interpret harm and how we seek resolution. Some grow up in environments where forgiveness is exalted; others in cultures that prize honour and retribution. Childhood trauma can make someone react defensively, even violently, to perceived threats. Meanwhile, society offers us scripts and systems like laws, courts, and ethical norms that channel our desire for balance into accepted forms of justice.

But even within those systems, revenge lingers. When a judge delivers a harsh sentence, is it justice, or a civilised form of vengeance? When a victim’s family speaks of “closure,” are they seeking truth, or symbolic retaliation?

The answer, often, is both.

A Blurred Line, Not a Bright One

To insist that justice is always impartial, institutional, and moral is to ignore its emotional roots. To suggest that revenge is always brutish, irrational, and primitive is to dismiss the moral conviction it often contains. In reality, both arise from the same psychological ground. What differs is how they are cultivated, justified, and interpreted.

The distinction is not in the feeling, but in the framing. In our capacity to reflect, to ask: why do we punish? What do we hope to restore? Justice and revenge are not enemies. They are siblings, raised in the same house, fed by the same fire, but taught to walk different paths.

Conclusion

Perhaps Aeschylus was not declaring the death of revenge, but merely dressing it in robes. Perhaps Shakespeare’s Hamlet never found justice because he never truly escaped the lure of vengeance. And perhaps Dostoevsky’s deepest insight in The Brothers Karamazov or Crime and Punishment, is that we are too fragile, too haunted by pain, to separate justice from revenge cleanly.

In the end, justice may be revenge filtered through memory, morality, and reason. Maybe what I am trying to express in this article is that they are both human and both deserve to be understood.

Written and Published by Sergios Saropoulos

Sources

- Aeschylus. The Oresteia. Translated by Robert Fagles, Penguin Classics, 1984.

- Plato. The Republic. Translated by G.M.A. Grube, revised by C.D.C. Reeve, Hackett Publishing, 1992.

- Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. Edited by Harold Jenkins, The Arden Shakespeare, 1982.

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor. The Brothers Karamazov. Translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002.

- Greene, Joshua D., et al. “An fMRI Investigation of Emotional Engagement in Moral Judgment.” Science, vol. 293, no. 5537, 2001, pp. 2105–2108.

- Koenigs, Michael, et al. “Damage to the Prefrontal Cortex Increases Utilitarian Moral Judgments.” Nature, vol. 446, 2007, pp. 908–911.

- Nussbaum, Martha C. Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Nussbaum, Martha C. Anger and Forgiveness: Resentment, Generosity, Justice. Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Haidt, Jonathan. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. Pantheon, 2012.

- Greene, Joshua, and Haidt, Jonathan. “How (and Where) Does Moral Judgment Work?” Trends in Cognitive Sciences, vol. 6, no. 12, 2002, pp. 517–523.

About the Creator

Sergios Saropoulos

As a Philosopher, Writer, Journalist and Educator. I bring a unique perspective to my writing, exploring how philosophical ideas intersect with cultural and social narratives, deepening our understanding of today's world.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.