Kosovo: A Century of Conflict and Tragedy

Kosovo: from Sjenica to Meja, a century of hate, political turmoil and tragedies.

Kosovo’s past is marked by centuries of conflict, loss, and deeply rooted animosities. The names Sjenica and Meja may not be widely recognized outside the Balkans, yet they are etched into the historical memory of those who have lived through the turbulence of this region. These places have been the backdrop for acts of violence, political oppression, and shifting power dynamics that have defined the complex relationship between Serbs and Albanians.

The relevance today.

Few people outside of the Balkans, have lots of memories from the dissolution of Yugoslavia and the chaos it created in the Southern Balkans. I would not blame you, regardless of remembering it or not. The 90s were a period of such geopolitical turmoil, that the complete destruction of Yugoslavia remains a foggy memory covered by migration stories and brutal war crimes. Unfortunately in this article, I will emphasize on the second.

But before we move to that, let's have a look at the current situation in Kosovo, today and let's see why Kosovo is monopolizing the Western media's international coverage, for one more time.

The argument of the license plates

The Balkans have long been a geopolitical fault line, and Kosovo remains a microcosm of its enduring tensions. While many outside the region remember the break-up of Yugoslavia as a distant memory, for those who lived through it, the dissolution was more than political—it was deeply personal, resulting in mass displacement, war crimes, and a legacy of unresolved grievances.

Today, Kosovo finds itself once again at the center of international headlines. Recent tensions over license plates—seemingly trivial on the surface—have reignited old hostilities. Serbia has placed its forces on high alert in response to Kosovo’s decision to enforce new regulations on Serbian-issued plates, a move seen as a direct challenge to Serbian influence in the region. Protests, roadblocks, and the deployment of security forces have heightened fears of renewed violence.

Roadblocks at the border, shootings, and assaults on journalists have threatened months of negotiations between Kosovo and Serbia that have been facilitated by the EU. A long-running conflict between the two nations has approached a breaking point once more, with additional barriers being erected and Serbia putting its forces in high readiness after Kosovo sent Albanian-Kosovarian police into its northern, Serb-dominated territories. After firing the Serb-Kosovarian police of Northern Kosovo, and in that way, violating the peace treaty. Although Serbians removed the barriers after 48 hours, there are still points of contention, and there are growing concerns that an agreement between the two nations would not be completed before a projected March 2023 deadline.

Yet, to understand why such an issue could escalate into a potential crisis, one must look beyond the present and delve into Kosovo’s troubled past.

The conflict over Kosovo's intentions to punish people of ethnic Serb descent who refuse to give up their licence plates issued by Belgrade has not been resolved to this day, and as a result, the EU, US, and Nato have expressed concern.

Why the hate?

Many who are not familiar with ethnic violence and thus Balkan history might be confused on how these people remained under the same rule for centuries and even in the 20th century, till the dissolution of Yugoslavia.

Because this article might not be enough to explain the whole history of the Ottoman Empire, I will emphasize on the 20th-century history of the area, and the violence that kept happening till the end of the century. It is not news that many minorities and different ethnic identities lived under the Ottomans and many of them hated each other, for a plethora of reasons, including the Ottomans. But what happened after the decay and fall of the Ottoman Empire and the creation of Yugoslavia, that lead to this non-stopping hatred, between people that co-existed for thousands of years.

Sjenica and the dying song of the Ottoman oppression in the Balkans.

Even before 1901, a series of killings of Serbs were committed by Albanians in the Ottoman Empire's Kosovo Vilayet (present-day Serbia, Kosovo, and North Macedonia). Serbs were persecuted and charged of working as Serbian agents, in order to achieve independence for Serbs against the Ottoman Empire. Serbs, mostly from the border regions, fled to Serbia as a result of the ensuing chaos. The Serbs were attacked by Albanian soldiers who took part in the Greco-Turkish War (1897), in the side of Turks, but did not turn their weapons in to the authorities. Albanians set fire to Sjenica, Novi Pazar, and Pristina in May 1901. In Pristina, the Albanians went on the rampage and massacred hundrends of Serb civilians including families and children. The Serb-dominated Ibarski Kolain (today known as North Kosovo), a forested area with around 40 Serbian villages, was always a concern for the ruling Ottomans and their allies the Albanians.

Overall, from the 1737 attacks at Kačanik and Kosovska Mitrovica till the 1901 attacks in Northern Kosovo and Pristina, it is estimated that around 10.000 Serbian civilians have lost their lives by the Albanian and Ottoman-Albanian forces.

Albanian War crimes in WW2

Of course, the gruesome period of WW2 could not be missing from the different eras of war crimes committed by both sides. From the Albanian side tens of war crimes and mass killings were committed against the Serbs from 1941 till 1944. Including the Ibarski Kolašin massacres, when the Albanian forces burnt down 22 Serbian villages, leaving tens of people dead and hundreds of people homeless. To the Peja massacres with 230 Serbs killed.

ΤΗΕ ΟΤΗΕR SIDE

The counter war-crimes

If you could see a diagram of war crimes committed in the area of Kosovo from the 19th century till the 1940s you would see that in most cases the victims were the Serbian population and the perpetrators were the Albanian or the Ottoman Albanian forces. But this changes drastically in the 1990s, with 20 of 24 internationally recognized war-crimes and massacres being committed by mainly Serbian forces, against the Albanian populations of Kosovo, and only 4 having Serbian victims. But to understand why, we need to explain what happened at the end of WW2 and the creation of the Socialist Republic or (Republics) of Yugoslavia.

The Rise and Fall of Yugoslavia

Following World War II, Kosovo was absorbed into Socialist Yugoslavia under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito. While officially an autonomous province within Serbia, Kosovo’s Albanians often felt marginalized. Tensions flared in the 1980s following Tito’s death, culminating in protests and violent crackdowns.

Slobodan Milošević’s rise to power in Serbia in the late 1980s marked a turning point. His nationalist rhetoric fueled anti-Albanian sentiment, stripping Kosovo of its autonomy and imposing direct rule. The Albanian population, in turn, mobilized resistance movements, with the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) emerging as a key player.

The beginning of Socialist Yugoslavia

After the end of Nazi occupation and the liberation of Yugoslavia by the Yugoslavian Partisans and partly by the Red Army. Elections were held on November 11th, 1945, and all 354 seats were won by the Communist-led People's Front. King Peter II, the former King of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, was overthrown by Yugoslavia's Constituent Assembly on November 29 while he was still in exile, and the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia was proclaimed. With that, all parts of the opposition had been wiped out, and Marshal Tito now had complete authority.

Under this political status quo of the late 1940s, Kosovo became a part of the Socialist Republic of Serbia. But remained as an autonomous province with the name of SAP Kosovo. Having the same autonomous status as SAP Vojvodina, an area in Northern Serbia. The Autonomous Region of Kosovo and Metohija (Serbo-Croatian: Аутономна Косовско-Метохијска Област / Autonomna Kosovsko-Metohijska Oblast), faced a plethora of political issues from its early stage. Yugoslavia intensified some policies after the separation with the Cominform in 1948, notably harsher collectivization. As a result, grain output in Kosovo was significantly reduced, and food shortages were experienced throughout Yugoslavia. Parallel to this, the Albanian government started to criticise Yugoslav rule in Kosovo; in response, the Yugoslav government cracked down on the local populace in an effort to root out "traitors" and "subversives," though the first underground pro-Tirana organisation was not established until the early 1960s.

After the constitutional changes in 1963, Kosovo was given the same status as Vojvodina and was declared an independent province. In addition to national tensions, there were considerable ideological differences between ethnic Albanians and the Yugoslav and Serbian governments, particularly with regard to relations with neighbouring Albania. Due to accusations that they supported Enver Hoxha's Stalinist policies, harsh repressive measures were enforced on Kosovo Albanians. A show trial was staged in Pristina in 1956, during which several Albanian Communists from Kosovo were found guilty of infiltrating Albania and sentenced to lengthy prison terms.

During this period, Islam was persecuted in Kosovo, and both Albanians and Muslim Slavs were pushed to leave for Turkey by claiming to be Turks. [19] Serbs and Montenegrins controlled Kosovo's administration, security forces, and industrial employment at the same time. [19] In the late 1960s, Albanians protested against these circumstances, calling the government's actions in Kosovo colonialist, calling for Kosovo to become a republic, or expressing support for Albania.

The King is Dead! Long Live the King!

After Josip Broz Tito's death in 1980, the aspirations by the local governing elite, which was dominated by Albanians, to be recognised as a parallel republic to Serbia within the Federation were rekindled. The 1981 protests in Kosovo were launched by Albanian students in March of that year. What began as a social protest quickly escalated into violent mass rioting with nationalist demands that the Yugoslav authorities had to use force to put an end to. The number of non-Albanians leaving the country rose, and there was a sharp rise in ethnic tensions between Albanians and non-Albanians. Violent attacks within the community targeted Yugoslav officials and other representatives of power in particular.

The 1987 Parain massacre and the 1985 "ore Martinovi" incident both contributed to the climate of racial animosity. Both were incidents that targeted Yugoslavian civilians conducted by Albanian nationalists. The anti-bureaucratic revolution, which Serbian authorities carried out in 1988 and 1989, saw the removal of the provincial leadership in November 1988 and a severe loss in Kosovo's autonomy in March 1989.

On 28 June 1989, Milošević led a mass celebration of the 600th anniversary of the 1389 Battle of Kosovo. One of the key moments in the history of Kosovo's ongoing crisis was Milosevic's speech in Gazimestan, which launched his rise to political prominence. Milosevic lead the succeeding Serbian nationalist movement which played a role in the Yugoslav Wars and in the war crimes committed.

Meja

Of the war crimes committed, the most atrocious for their barbarity is the one committed in Meja. On April 27, 1999, during the Kosovo War, there were at least 377 mass executions of Kosovo Albanian civilians known as the Meja massacre (Albanian: Masakra e Mejs). According to the aftermath research, 36 of the victims were under the age of 18. It was carried out by Serbian police and Yugoslav Army forces during the Reka Operation, which got underway after the Kosovo Liberation Army killed six Serbian officers (KLA). The executions took place in Meja, a village close to Gjakova. At a checkpoint near Meja, the victims were removed from refugee convoys, and their relatives were instructed to travel to Albania. Boys and men were divided, and then they were killed on the road. The mass graves at Batajnica contained many of the victims' bodies. Several Serbian army and police officers have been found guilty of involvement by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

Another example of the atrocities committed by the Serbian forces is the Vushtrri massacre when The Serb Special Forces trapped Albanian refugees who had fled the combat between the Yugoslav Army and the KLA (who suspected that some KLA members were fleeing the fighting with the refugees). The Special Forces targeted 120 individuals they believed to be KLA deserters, shot them repeatedly, and then buried their dead in a mass grave not far from Gornja Sudimlja.

Bosnia

It is important to note that at the same time, during, the Yugoslavian dissolution, the Srebrenica massacre, one of the worst massacres in the last century was committed. When 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys were murdered and the remainder of the population (between 25,000 and 30,000 Bosniak women, children and elderly people) was forced to leave the area.

The Aftermath war-crimes of the Kosovo War

In the aftermath of the Kosovo War, crimes were also committed against the remaining Serbian populations of Kosovo with estimations of more than 100 deaths of Serbian civilians from the aggression of Albanian nationalists. From June to October 1999, in the wake of the Kosovo War, members of the KLA's Gnjilane group kidnapped, tortured, and massacred several Kosovo Serb citizens in the town of Gnjilane Between June and October 1999, the so-called "Group of Gnjilane", consisted of ethnic Albanians, is thought to have abducted 159 Serb civilians and killed at least 51 individuals.

The European Future and the West

With the fall of the Iron Curtain and with many former "Socialist" countries joining the West and NATO, even the nostalgists of the Yugoslavian dream realized that their countries future lays with the West and especially with the European Union, with some of the former countries of Yugoslavia already joining the E.U. Like Slovenia or Croatia, with both of them adopting euro as their national currency. Whereas Serbia, even though that, has already applied for EU membership. Seems to retain strong connections with Russia and China, two countries that are perceived as the global superpowers of the East. But with the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and with the recent Russian failures on the Ukrainian front, even Serbia has been reconsidering its friendly stance towards Russia.

These circumstances can help us understand that in the future, any crisis between Kosovo, Albania and Serbia will be resolved through diplomatic dialogue, or at least both sides will try to resolve it with diplomacy, with the help of the E.U. and the auspices of the United States of America. Without this excluding any cases of retaliation.

Written and Published by Sergios Saropoulos

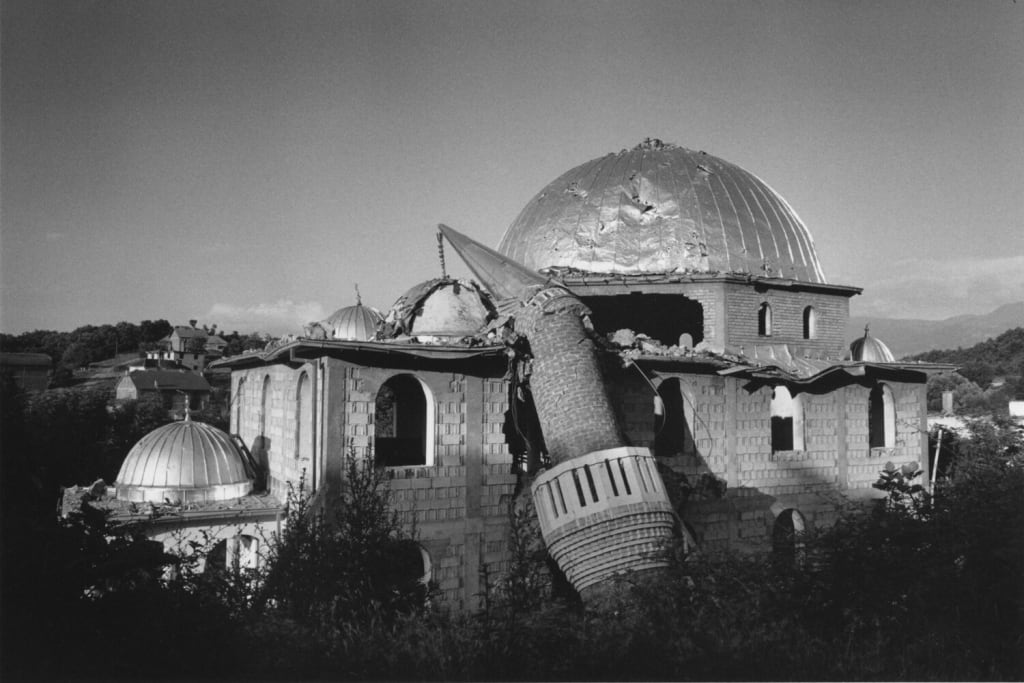

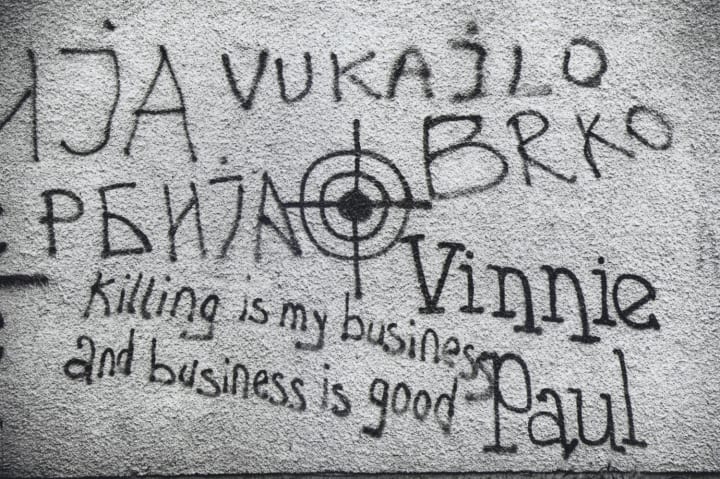

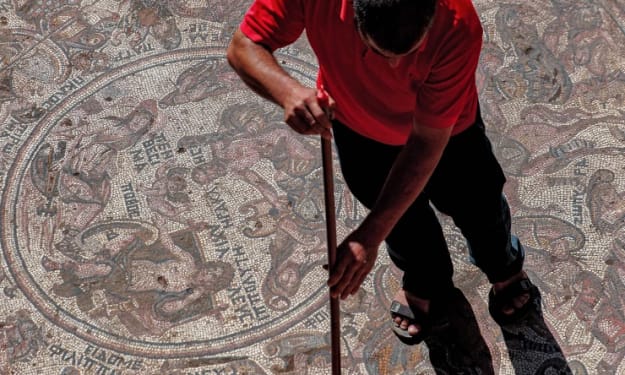

P.S. The majority of the pictures I used, come from the beautiful collection of the photographer Gary Knight. I am leaving the link of his webpage here so you can have a look; http://www.garyknight.org/evidencekosovowarcrimesgk

About the Creator

Sergios Saropoulos

As a Philosopher, Writer, Journalist and Educator. I bring a unique perspective to my writing, exploring how philosophical ideas intersect with cultural and social narratives, deepening our understanding of today's world.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.