A Mudlark Remembers

A story from the silt

A man is standing on the lip of the Thames with a watch in his hand, gripped tight. There is a girl behind him. She knows not to go too close, she knows he is crying. His back has broadened to hide the shame of his emotion. She can see the constriction in his muscles from where she is stood. There is a faint sound of gulls and heavy machinery but its deadened by thick London fog.

It’s me, I am the girl. I work for this man. Dodgy work, cash in hand, down on the docklands.

George is the man’s name - I know him through my other job at the pub. He needed some help around the yard, chasing up what customers owed for their lock-ups and putting it all into spreadsheets. Sending emails, doing the adding up. George learned to read and write in prison. I learned at school - we are from different worlds but I like him and I want to know why he is crying.

I walk back over the pitted grey dirt to the Portacabin. I sit down and crane under my desk to turn the fan heater on, it whirrs beneath me. My chair is big and comfortable - though it has ash burns all over the upholstery. The office is partially fitted out with antique furniture seized from some tenants who left without paying their debt which gives it a grand feel that clashes with the porridge-coloured stucco walls. The room smells of stale marijuana and mildew. The other day I had asked the men to smoke in the other room as I realised my lids were growing heavy with passive smoke by the afternoon and though the work is easy - I find myself easily distracted by the large television in the corner which is on silently for most of the day.

One morning I had been sure I was hallucinating. There were young men in the yard, in the TV, in the yard. Four boys - a pop band, ducking and diving between the rusting industrial containers, pointing to the camera confidently as a convertible car spun dirt with its wheels. Every detail had been the same down to the oil drum we use as a fire pit on colder days. I had looked out of the window to see if they were there now in some kind of Truman Show scale set-up and had seen nothing but a seagull sifting through a bin and a customer in the misty distance struggling to lock his padlock. I had swallowed anxiously trying to cultivate the dampness of rain in my throat. POP, Music had torn suddenly through the silence like the fabric of reality was ripping and I had levitated out of my seat only to find George behind me with the remote cackling with a wide grin, clutching his splitting side.

“I rented the yard out to those boys’ manager about 9 months ago, Wish I hadda charged more now” he smiled, gold tooth glinting in the fluorescent light. Thinking back to this levity of this day makes the weight of Georges grief seem more cloying now.

I look back out of the window. George is still standing there, now empty handed.

I rewind the CCTV on the small desktop screen, a grainy version of the same scene appears and I watch the George of 5 minutes past gather momentum in his shoulder and launch the watch far into the water. I wonder why he has done that.

The television is on as normal, tuned to the news. I watch the rolling red scroll at the bottom of the screen talk of fatal violence breaking out on a container ship that has been anchored off the coast by Southend for some time. The video pans to show the ship out to sea, an optical illusion makes it look like it is floating above the horizon. There is another ship, free and sailing in the distance in the frame. I watch the face of the news anchor and try to lip read before giving up and turning her up.

She says that the shipping company is bankrupt. What happens when a shipping company is bankrupt is that they cannot dock anywhere. All but a few are taken off the ship leaving only a skeleton crew until the debt can be paid. I think of the indefinitely floating ship and the skeleton crew and sigh at the reality of the neglected, left to their own devices.

George walks into the portacabin and the air in the small room suddenly itches. He see’s that I have been watching him on CCTV. His eyes are like jellied eels. His balled fists are two pies and his heart is mash. “My father was not a very nice man, Jennifer”

I don’t know what to say, so I say nothing.

“He’s brown bread”

“I am so sorry”

“Dont be”

“Shall I put the kettle on”?

“You can’t, Ive just thrown it in river” a rye smile begins to spread weakly across his gentle face.

“What”?

“Kettle is Watch in Rhyming Slang, Jen. Kettle and Hob, Fob. Watches used to be on fob chains in them days.”

“Ahh”

“I’ll drive you home early today. I’ve got to go and see my brother”

-⃝

When I am in bed that night. I dream that I am wearing a black suit emblazoned entirely with creamy buttons. A Pearly Queen of Bethnal Green. I climb an extremely long and unstable ladder to the moon and pull the opal orb loose from its thread and stitch it to my lapel. I walk down Bethnal Green Road and visit the constellation of pubs. The Sun, The Star and The Misty Moon. In each one I drink one glass of red wine and make sure to smash the glass before leaving.

I wake feeling hungover and listless.

George is outside my flat at the same time as he is every weekday. We drive to the cafe in Bow where we eat breakfast most mornings.

“Jennifer this is my brother, Clarence.”

“Hello Clarence” I say.

“Hello Jenny” says Clarence, nodding.

“We’ve got to go to the bank and sort summin’ out. Get what you want to eat and I’ll be back to pay.” George says this quietly. I think he is a true gentleman, though I once saw him threaten to beat another man blue with a stool.

I remember George talking about his brother Clarence. About Mudlarking down on the riverbank as children. “Mudlarking is just a hobby now Jen” George had said. I didn’t know why he needed to reassure me of this until I looked into it and found in the long ago times, poor children would scour and sift the silty banks of the Thames to make a filthy living. Finding medieval pottery shards, clay pipes and sometimes Roman Coins. Right up until 1904 it was considered a job.

He said Clarence and him would find stuff valuable enough to flog sometimes. In the Seventies their mother had worked at the Matchbox Cars Factory in Hackney Wick. George told me once that the lady workforce would pitch the duds out of the factory window and collect them later but many of them ended up in the canal. The ones that didn’t the boys would sell on for pennies.

I picture hundreds of eroding toy cars driving up the bottom of the canal-bed, embedded in sludgy traffic for eternity. I picture a well-to-do hobbyist some years from now finding the watch and hypothesising about its owner. I picture Clarence and George’s intestines writhing like eels with the discomfort of death and resentment in the queue at the bank.

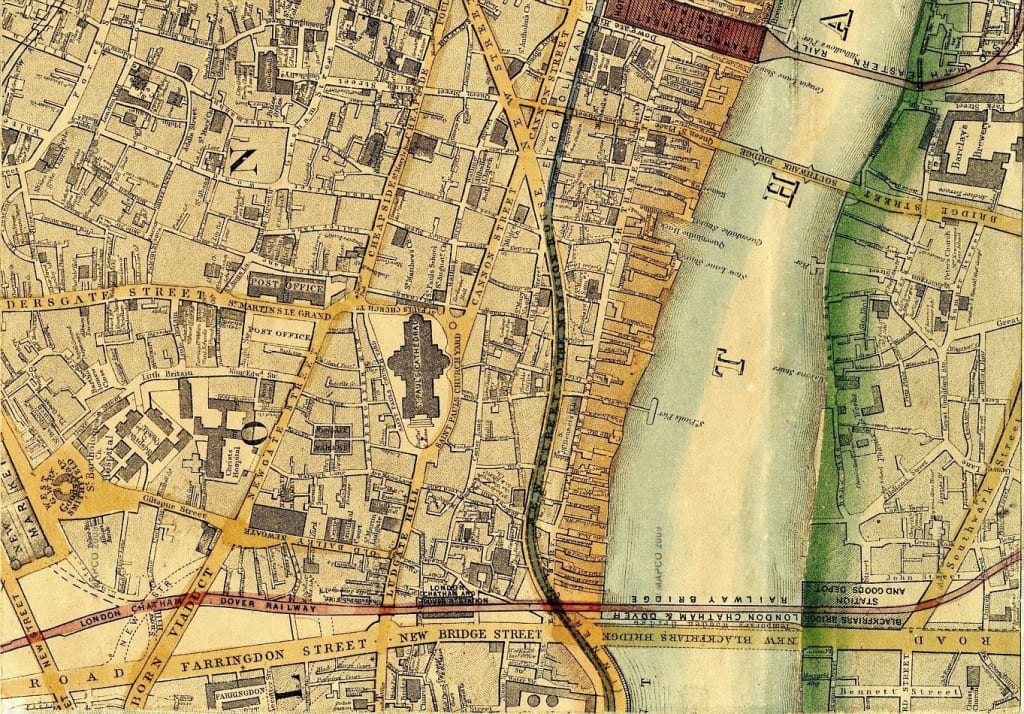

It becomes clear to me that the sediment at the bottom of Thames is the sub-conscious of the city. Never gone, suppressed by current and gravity, dredged by strangers. Disturbed.

I watch George move slowly through the window of the Café. Clarence is leaving.

I reach into my pocket and clasp my hand around a single pearl button.

-⃝

About the Creator

Nathalie Limon

Human in semi-good condition, fascinated by the human condition.

See more of me on instagram: @nathalie.limon_moves

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.