Was the Roman Colosseum Really as Bloody as Gladiator Makes It Look?

From executions to pro fighters, how the real Colosseum compares to the brutal world of Gladiator

This story was created with the partial help of AI tools and then revised by the author.

When people think of ancient Rome now, a lot of them are not picturing marble statues or quiet philosophers. They are seeing Russell Crowe standing in the sand of the Colosseum, asking a roaring crowd if they are entertained. The movie Gladiator burned that image into everyone’s brain so deeply that many viewers walk away believing the arena was one nonstop slaughterhouse where every fight ended in death.

The truth is more complicated and honestly more interesting. The Colosseum really was a place of public cruelty on a scale that is hard to imagine today, but it did not work exactly the way the movie shows it.

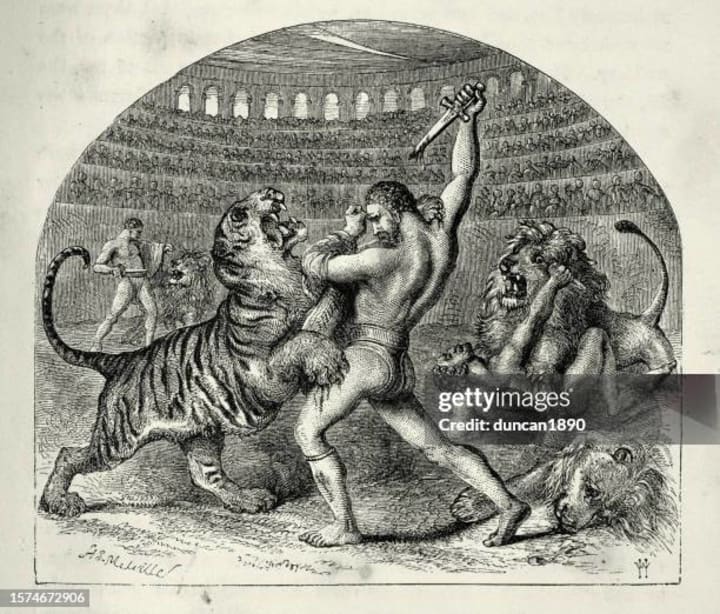

On a big festival day in Rome, you were not getting anything close to a wholesome afternoon at the games. The program usually unfolded in acts. Mornings could be filled with animal shows and hunts. Lions, leopards, bears, even more exotic animals were driven into the arena for staged hunts that showed off Roman control over nature and faraway territories. It was a live picture of empire under the sun.

The middle of the day was where things got truly sickening. This is when many public executions took place. Condemned people might be crucified, burned, beheaded, or thrown to animals in what the Romans called punishment to the beasts. Sometimes these executions were dressed up as little plays that reenacted myths. The ending was always the same. The person in the role of the doomed character did not get back up.

Only in the afternoon do you usually get to what most of us think of when we hear the word gladiator. These were trained fighters, not random prisoners tossed into the sand. They trained in schools, followed strict regimens, ate carefully planned diets, and had access to medical care that was surprisingly decent for the time. The whole point was to build skill and drama. They wanted fighters who could put on a show.

That is where Gladiator leans hardest into movie logic. The film makes it feel like every single match is a fight to the death, that the crowd will not be satisfied unless someone dies on the spot. In reality, death was always a risk in the arena, but it was not the automatic outcome of every bout. Many historians estimate that a clear majority of defeated gladiators actually survived their fights, especially in the first and second centuries. That still means a terrifying number of men died, but the arena for them was more like a brutal professional sport than a guaranteed execution.

The reason is simple. A good gladiator was expensive. Owners and sponsors invested money and time in training these fighters. They advertised them, matched them for maximum excitement, and sometimes even built them into minor celebrities with loyal fans. Killing off every skilled fighter the first time he lost would be like an owner burning a star players contract just to get one dramatic moment. It did happen, but usually only when someone fought badly, broke the rules, or when a sponsor wanted to send a very specific message.

Executions and beast shows were the part of the day that worked like a conveyor belt of death. Gladiator mostly blends those categories together. It takes the horrors of the execution block and the controlled violence of gladiator matches and compresses them into the same type of contest. That is how you end up with a movie version of the Colosseum where almost everyone you meet in the arena is as good as dead the second they step onto the sand.

At the same time, the movie does nail something that is easy to miss if you only look at numbers. The games were not only entertainment. They were a tool. Public violence reminded everyone who held power, who could give life, who could take it, and how cheaply human bodies could be used when the state wanted to make a point. The emperor in his box, the crowd demanding blood, the condemned person in the middle of it all, that triangle is very real.

This is also where the characters from Gladiator slide into history. Commodus truly was obsessed with his own image and did appear in the arena in person, something that shocked many elites. Marcus Aurelius really was the philosopher emperor whose death helped close out what later writers called the good times of Rome. Maximus himself is not a real person but he is built from real types. He is part professional fighter, part favored general, part wishful thinking about a moral man trapped inside a corrupt system. If you want to go deeper on that side of things, including the question of is maximus decimus meridius real?, that is something I explore a lot as a contributor at FlipTheMovieScript.

So was the Colosseum as bloody as Gladiator makes it look. In spirit, yes. In detail, not exactly. Over years and decades, thousands of people and countless animals died in Roman arenas. Some days in the Colosseum would absolutely have matched the worst scenes in the movie. You would have seen people mauled, executed in creative and cruel ways, and yes, gladiators dying in front of a screaming crowd.

But you also would have seen fighters saluted and spared, medical teams rushing into patch someone up, and familiar faces returning to the arena again and again. You would have seen rules and referees and negotiations over life and death, not just automatic slaughter every time.

The reality is still monstrous, just less simple than one big blood bath. That is what makes it worth talking about. The Romans were not cartoon villains. They were human beings cheering in the stands, laughing, gasping, and feeling entertained by what we now see as pure horror. Gladiator takes all of that and turns it into a tight, powerful story. History stretches it back out again and shows us the full, uncomfortable picture.

About the Creator

Flip The Movie Script

Writer at FlipTheMovieScript.com. I uncover hidden Hollywood facts, behind-the-scenes stories, and surprising history that sparks curiosity and conversation.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.