Viva’s People You Should Know

Viva Magazine’s Cultural Spotlight on Changemakers and Icons

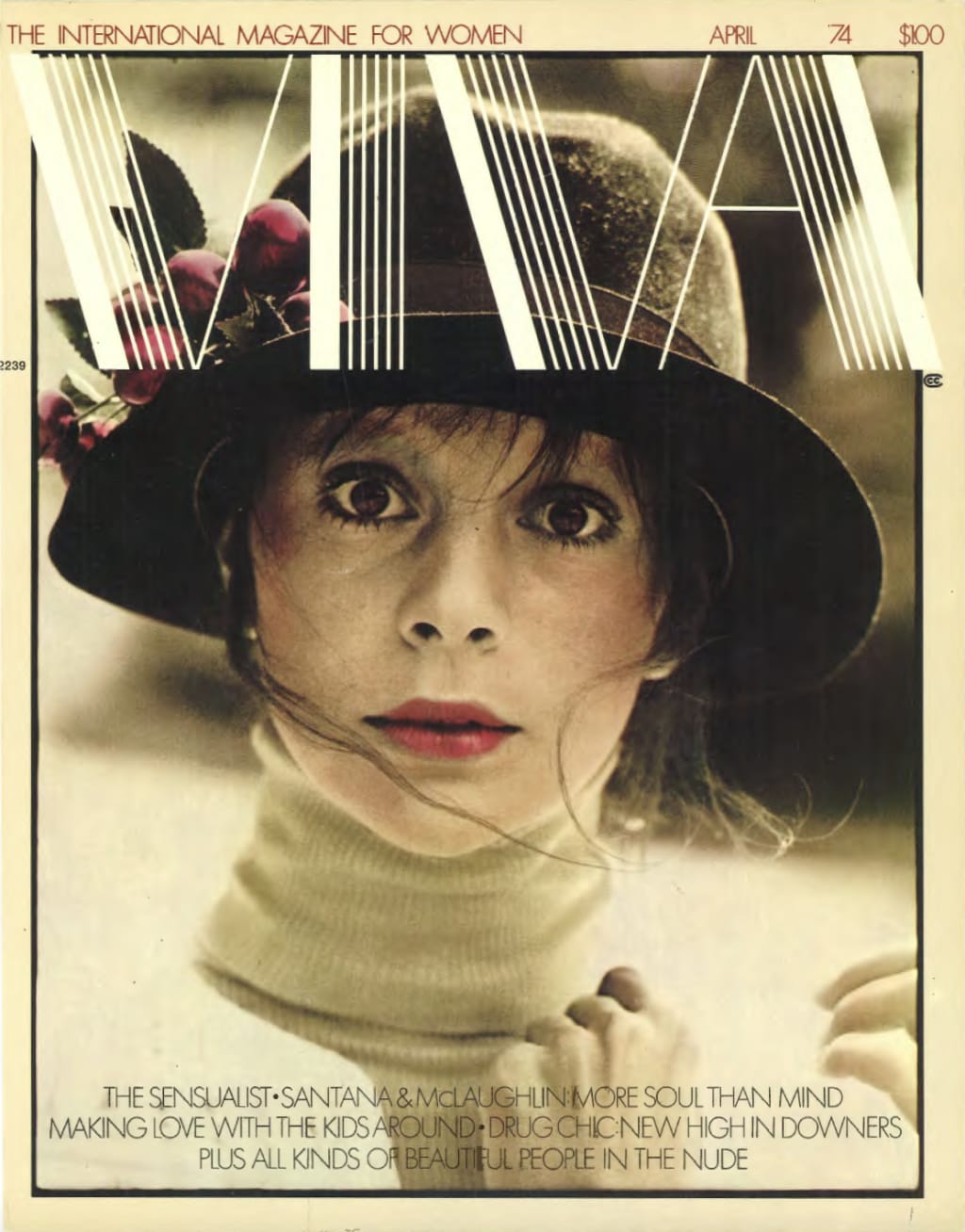

Launched by Penthouse magazine founder Bob Guccione in the 1970s, Viva magazine was a breaking barriers. It sought to bridge the worlds of fashion, politics, and culture, specifically with a focus on women. Penthouse pushed boundaries in sexual expression, but Viva magazine took a more sophisticated approach. Viva's audience was the progressive and independent women of the era. The magazine’s “People You Should Know” section became a hallmark, introducing readers to political changemakers, fashion icons, and cultural disruptors, while situating these figures within the broader cultural movements of the 1970s. Through these profiles, Viva created a valuable archive for historians, offering a snapshot of the influential personalities who shaped the era’s social landscape.

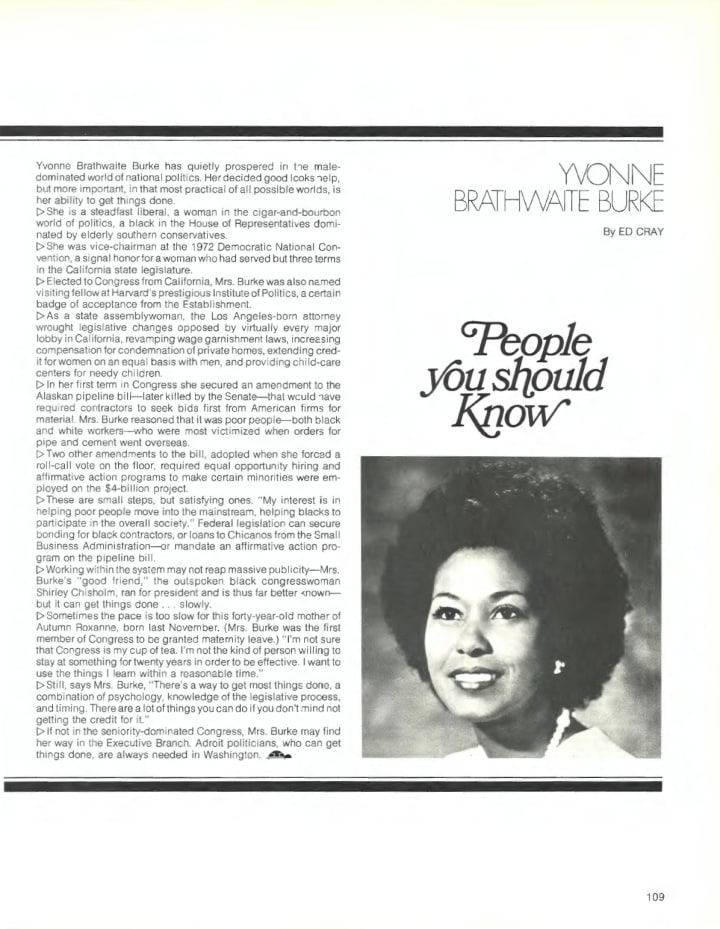

Viva, May 1974: Yvonne Brathwaite Burke, by Ed Cray

Yvonne Brathwaite Burke has quietly prospered in the male dominated world of national politics. Her decided good looks help, but more important, in that most practical of all possible worlds, is her ability to get things done.

- She is a steadfast liberal, a woman in the cigar-and-bourbon world of politics, a Black woman in the House of Representatives dominated by elderly southern conservatives.

- She was vice-chairman at the 1972 Democratic National Convention, a signal honor for a woman who had served but three terms in the California state legislature.

- Elected to Congress from California, Mrs. Burke was also named visiting fellow at Harvard's prestigious Institute of Politics, a certain badge of acceptance from the Establishment.

- As a state assemblywoman, the Los Angeles-born attorney wrought legislative changes opposed by virtually every major lobby in California, revamping wage garnishment laws, increasing compensation for condemnation of private homes, extending credit for women on an equal basis with men, and providing child-care centers for needy children.

- In her first term in Congress she secured an amendment to the Alaskan pipeline bill – later killed by the Senate – that would have required contractors to seek bids first from American firms for material. Mrs. Burke reasoned that it was poor people – both Black and white workers – who were most victimized when orders for pipe and cement went overseas.

- Two other amendments to the bill, adopted when she forced a roll-call vote on the floor, required equal opportunity hiring and affirmative action programs to make certain minorities were employed on the $4-billion project.

- These are small steps, but satisfying ones. "My interest is in helping poor people move into the mainstream, helping Blacks to participate in the overall society." Federal legislation can secure bonding for Black contractors, or loans to Chicanos from the Small Business Administration – or mandate an affirmative action program on the pipeline bill.

- Working within the system may not reap massive publicity-Mrs. Burke's "good friend," the outspoken Black congresswoman Shirley Chisholm, ran for president and is thus far better known – but it can get things done…slowly.

- Sometimes the pace is too slow for this forty-year-old mother of Autumn Roxanne, born last November. (Mrs. Burke was the first member of Congress to be granted maternity leave.) “I’m not sure that Congress is my cup of tea. I'm not the kind of person wiIIing to stay at something for twenty years in order to be effective. I want to use the things I learn within a reasonable time."

- StilI, says Mrs. Burke, "There's a way to get most things done, a combination of psychology, knowledge of the legislative process, and timing. There are a lot of things you can do if you don't mind not getting the credit for it."

- If not in the seniority-dominated Congress, Mrs. Burke may find her way in the Executive Branch. Adroit politicians, who can get things done, are always needed in Washington.

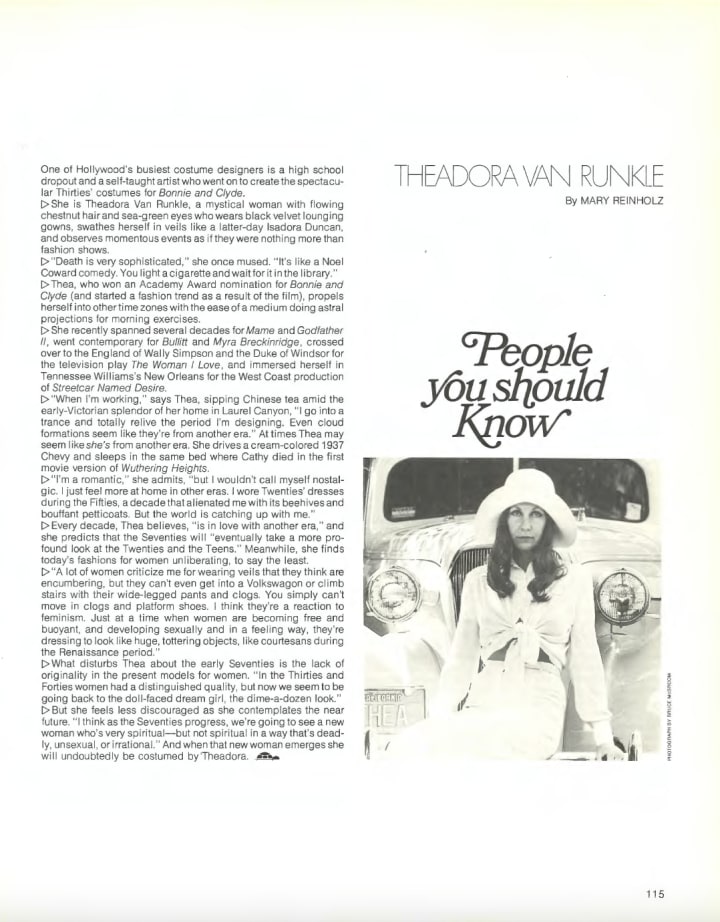

Viva, April 1974 - Theadora Van Runkle, by Mary Reinholz

One of Hollywood's busiest costume designers is a high school dropout and a self-taught artist who went on to create the spectacular Thirties' costumes for Bonnie and Clyde.

- She is Theadora Van Runkle, a mystical woman with flowing chestnut hair and sea-green eyes who wears black velvet lounging gowns, swathes herself in veils like a latter-day Isadora Duncan, and observes momentous events as if they were nothing more than fashion shows.

- "Death is very sophisticated," she once mused. "It's like a Noel Coward comedy. You light a cigarette and wait for it in the library."

- Thea, who won an Academy Award nomination for Bonnie and Clyde (and started a fashion trend as a result of the film), propels herself into other time zones with the ease of a medium doing astral projections for morning exercises.

- She recently spanned several decades for Mame and Godfather II, went contemporary for Bullitt and Myra Breckinridge, crossed over to the England of Wally Simpson and the Duke of Windsor for the television play The Woman I Love, and immersed herself in Tennessee Williams's New Orleans for the West Coast production of Streetcar Named Desire.

- "When I'm working," says Thea, sipping Chinese tea amid the early-Victorian splendor of her home in Laurel Canyon, "I go into a trance and totally relive the period I'm designing. Even cloud formations seem like they're from another era." At times Thea may seem like she's from another era. She drives a cream-colored 1937 Chevy and sleeps in the same bed where Cathy died in the first movie version of Wuthering Heights.

- "I'm a romantic," she admits, "but I wouldn't call myself nostalgic. I just feel more at home in other eras. I wore Twenties' dresses during the Fifties, a decade that alienated me with its beehives and bouffant petticoats. But the world is catching up with me."

- Every decade, Thea believes, "is in love with another era," and she predicts that the Seventies will "eventually take a more profound look at the Twenties and the Teens." Meanwhile, she finds today's fashions for women unliberating, to say the least.

- "A lot of women criticize me for wearing veils that they think are encumbering, but they can't even get into a Volkswagon or climb stairs with their wide-legged pants and clogs. You simply can't move in clogs and platform shoes. I think they're a reaction to feminism. Just at a time when women are becoming free and buoyant, and developing sexually and in a feeling way, they're dressing to look like huge, tottering objects, like courtesans during the Renaissance period."

- What disturbs Thea about the early Seventies is the lack of originality in the present models for women. "In the Thirties and Forties women had a distinguished quality, but now we seem to be going back to the doll-faced dream girl, the dime-a-dozen look."

- But she feels less discouraged as she contemplates the near future. "I think as the Seventies progress, we're going to see a new woman who's very spiritual-but not spiritual in a way that's deadly, unsexual, or irrational." And when that new woman emerges she will undoubtedly be costumed by Theadora.

About the Creator

OG Collection

Exploring the most significant and hidden stories of the 20th century through iconic magazines and the titan of publishing behind them.

Comments (3)

The writing is rich in detail and vividly portrays the accomplishments and personalities of the featured figures, such as Yvonne Brathwaite Burke and Theadora Van Runkle, situating them within their historical and cultural contexts. The language is descriptive and engaging, offering a blend of narrative and factual information that brings these individuals to life. However, the dense, lengthy paragraphs could be streamlined for easier readability, with clearer transitions and emphasis on key points. Overall, the style is informative and well-researched but could benefit from more concise expression to enhance engagement.

Congratulations on achieving top story status!

I love this