We’re used to hearing about the Jacobites from an English perspective as if they were foolish dreamers chasing tartan myths. But that’s a distortion. When you trace the road from 1707 to 1745, the Jacobite risings look less like romantic misadventures and more like a nation’s last desperate attempt to right a wrong.

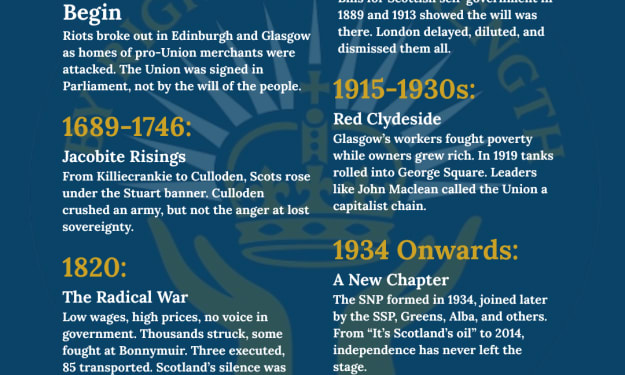

1707: A Union Signed in Weakness, Not Strength

The Act of Union didn’t come out of nowhere. By 1707, Scotland had been chipped, starved, and battered for over a century.

• Our population flatlined while England’s doubled.

• Tens of thousands had been killed in wars or shipped abroad.

• The famine of the 1690s wiped out up to 15% of our people.

• Darien had bankrupted the elite.

When England dangled £398,000, the “Equivalent”, to cover Darien’s debts, desperate nobles signed. But the people were outraged. Riots broke out in Edinburgh, Glasgow, and beyond. The Union was not the will of the people; it was the will of a broken elite.

1708: The Fuse Is Lit

Within a year, the first Jacobite rising flared. James Francis Edward Stuart, the “Old Pretender”, tried to land in Scotland with French backing.

Bad weather and the Royal Navy stopped him, but the response on the ground told the real story: thousands of Scots were ready to rise. That should have been the warning.

The Union hadn’t healed wounds. It had poured salt into them.

1715: A Nation Strikes Back

By 1714, Queen Anne was dead and the throne had passed not to a Stuart, not even to an Englishman, but to George I - a German prince who could barely speak English, let alone care for Scotland.

It was the breaking point. John Erskine, the Earl of Mar, raised the Jacobite standard in 1715. Tens of thousands answered.

The reasons weren’t “romantic” at all:

• Betrayal of sovereignty: Scotland’s parliament was gone.

• Religious divisions: Presbyterians, Episcopalians, and Catholics all had reason to resent Hanoverian rule.

• Economic anger: Union hadn’t delivered prosperity. Taxes rose, trade favoured England, and Scots felt cheated.

• National pride: The Union was seen as a sell-out, signed by men who no longer spoke for the people.

At Sheriffmuir, the battle ended in stalemate, but the scale of the rising proved something: Scotland had not accepted Union, and never would quietly.

1719: Spain Smells Opportunity

Even Spain saw it. In 1719, they backed another rising, landing forces in the Highlands. It was smaller, poorly supported, and quickly defeated, but the fact it happened at all showed how unstable Britain remained.

1745: The Last Throw of the Dice

By 1745, almost 40 years after Union, resentment had only deepened. The promised wealth of empire never reached most Scots. The Highlands were under pressure from cultural suppression. Sovereignty felt like a memory.

When Charles Edward Stuart, Bonnie Prince Charlie, landed in the Highlands, he wasn’t just waving a Stuart banner. He was igniting every grievance Scotland had carried since 1707.

The campaign electrified the nation:

• Prestonpans (1745): Government forces routed in a single morning.

• Falkirk (1746): Another Jacobite victory.

• The march south reached as far as Derby.

For a moment, it looked possible: not just a Stuart restoration, but a Scotland restored.

Then came Culloden.

1746: Culloden and the Crushing of a Nation

The slaughter on that moor is remembered as the end of the Jacobite dream. But what was crushed that day wasn’t fantasy, it was resistance.

In the aftermath, the repression was brutal:

• Gaelic culture targeted for destruction.

• Weapons banned, tartan outlawed.

• Families broken, land seized.

Culloden wasn’t the end of a misguided cause. It was the silencing of a people who had dared to fight for what was stolen from them.

The Real Story

England’s version frames the Jacobites as reckless dreamers clinging to the past. But look at the record:

• The Union was signed by desperation, not consent.

• The people rioted, not rejoiced.

• Every rising was fuelled by real grievances - sovereignty lost, economy weakened, culture under threat.

The Jacobites weren’t chasing nostalgia. They were answering betrayal. We only have to read the Scottish Jacobite Manifesto to know.

From Pinkie in 1547 to Culloden in 1746, Scotland endured a century and a half of attrition, chipped away until Union was forced, and then punished when it resisted.

The Jacobite risings weren’t about clinging to the past. They were about fighting for a future stolen too soon.

About the Creator

Laura

I write what I’ve lived. The quiet wins, the sharp turns, the things we don’t say out loud. Honest stories, harsh truths, and thoughts that might help someone else get through the brutality of it all.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.