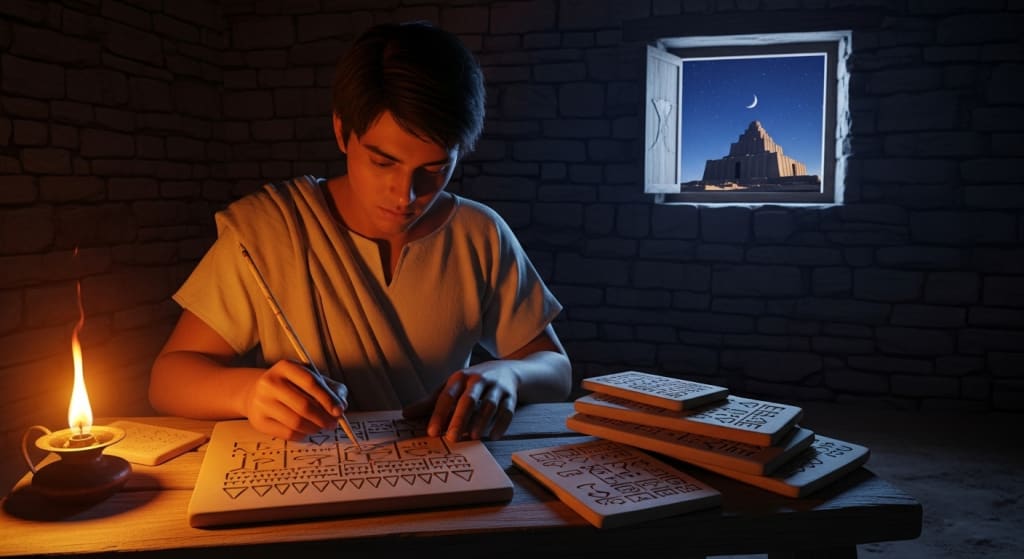

The air in the scriptorium was thick with the smell of damp clay and burning oil. I, Nabu-ahhe-iddin, apprentice scribe to the great House of Murashu, dipped my reed stylus into a small bowl of water and prepared to correct my mistake. A single, misplaced wedge. To any other, it was nothing. To my master, Shum-ukin, it was a crack in the foundation of the world.

“The word for ‘barley’ and the word for ‘debt’ are separated by the width of a single angle, boy,” he had growled, his voice like grinding stone. “A careless scribe does not record history. He invents lies that become truth.”

My punishment was to recopy the entire tablet—a record of a land dispute between two powerful landowners. It was tedious work, my fingers cramping as I pressed the triangular end of the stylus into the soft clay, forming the intricate, wedge-shaped script. A-na. To. Be-el. The lord. A-bi. My father.

My father was a farmer, his hands calloused from the plough, not soft from handling clay. He had sold our best goat to pay my apprenticeship, believing that a man who could read the celestial writing was closer to the gods than a king. “Words are power, Nabu,” he’d said. “They outlive stone.”

As I worked, a commotion erupted outside. Two men, their faces flushed with anger and the heat of the day, strode into the courtyard, followed by a retinue of servants. It was the disputing landowners, Bel-rimanni and Sin-iddinam. They had bypassed the lower officials and come straight to the source of all legal truth: the scribes.

“The canal runs ten cubits to the east of the marker stone!” shouted Bel-rimanni, a man built like a bull.

“Lies! The record from my grandfather’s time shows it fifteen cubits to the west!” countered Sin-iddinam, slender and sharp as a dagger.

They argued before Shum-ukin, who stood with the patience of the Tigris River. He did not look at them. He looked at me.

“Apprentice,” he said, his voice cutting through their shouts. “Fetch the archival case for District Seven. The case of burnt clay.”

My heart hammered against my ribs. The archives were a labyrinth of shelves holding thousands of tablets, the collective memory of our city. A mistake meant hours of searching. A failure meant disgrace.

I found the case, my hands trembling as I carried the heavy, fired-clay container to my master. He opened it, his fingers, old and knotted, moving with a gentle reverence as he sifted through the brittle tablets.

He selected one. It was small, darkened by time, its script a more archaic form of our own. He held it up to the two landowners.

“This,” Shum-ukin announced, “is the boundary stone agreement between your great-grandfathers. Witnessed by the priest of Enki and sealed in the year of the great flood.”

He handed the tablet to me. “Read it, Nabu-ahhe-iddin.”

All eyes turned to me. The bull and the dagger stared, their fates suddenly resting on the voice of a lowly apprentice. The ancient script was difficult, the wedges faded. I traced them with my finger, sounding out the words in my head first.

“From the date palm of Bel… to the well of Sin… the water-rights are divided… equally…”

I read the entire decree, my voice gaining strength. The boundary was, as Sin-iddinam had claimed, fifteen cubits to the west. But it also stipulated shared maintenance of the canal, a clause their own copies had lost.

Silence fell. The truth, spoken from a piece of fired mud, had disarmed them both.

Bel-rimanni, the bull, deflated. Sin-iddinam, the dagger, sheathed his anger. They had not been defeated by each other, but by the unassailable word of their ancestors.

As they left, Shum-ukin placed a hand on my shoulder. It was the first time he had ever touched me in kindness.

“You see, boy?” he said softly, looking at the tablet in my hands. “We do not just write lists of grain and sheep. We are the builders of the dam that holds back chaos. A king’s command is but wind. A law written in clay is stone. It is the memory of the tribe. It is the only thing that truly lasts.”

That night, as I finished my punitive tablet, I did not feel the cramp in my fingers. I felt the weight of the word. My father was right. I was not just a boy pressing shapes into mud. I was a guardian. I was the memory of my people, and in my careful, deliberate hands, I held the power to settle disputes, to define boundaries, to shape the very world, one tiny wedge at a time.

About the Creator

The 9x Fawdi

Dark Science Of Society — welcome to The 9x Fawdi’s world.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.