The Talking Walls of Angel Island

Imprisoned in the wooden building day after day, my freedom withheld

Throughout the U.S. Reconstruction Era, violence and bigotry towards Chinese Americans was business as usual.

Prior to Reconstruction, California Governor John Bigler delivered a speech to his state assembly in 1952. In his deliverance, he requested a ban on Chinese immigration. Bigler believed these migrants were ignorant to political participation and the court of law. He claimed they could never assimilate or become good citizens, much less become good jurors or voters.

In 1870, San Francisco’s Cubic Air Ordinance ordered that Chinese Americans could only rent rooms with less than 500 cubic feet of air per person. Chinese Americans could only live in spaces the size of a large walk-in closet, a small dorm room, or the cargo bed of a 12-foot U-Haul.

This San Francisco order was pushed by the leaders of the Anti-Coolie Association. Through the 1870s, this organization boycotted Chinese businesses and rioted throughout Chinatowns across the West Coast. Members described Chinese migrants as "yellow peril" and "cattle or hogs" unfit to exist amongst civilized human beings.

In 1871, a white Los Angeles police officer was shot while responding to a shootout between several Chinese men. In retaliation, a white and Latino mob publicly executed 20 Chinese Americans, marking one of the largest mass lynchings in American history.

In 1873, the Pigtail Ordinance (later deemed unconstitutional) required Chinese residents to cut off their braids — sacred symbols of the Chinese man. Under Chinese belief, the severing of braids condemned these men to great suffering in the afterlife.

In 1884, the Tape Family sued the San Francisco Board of Education for refusing to enroll their Chinese daughter into their public school. After the Tape family won the Supreme Court case, the Board of Education created a separate school for Chinese children.

In 1885, white miners in Rock Springs massacred at least 28 Chinese miners and drove out hundreds of Chinese Americans from Wyoming Territory. Two months later, white vigilantes on horseback rounded up 200 Chinese Americans to leave Tacoma, Washington by passenger train or freight train, or on foot. At the peak of 19th century American vigilantism, at least 168 communities kicked out Chinese residents.

The putrid pinnacle of the anti-Chinese movement was the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, spurred by John Franklin Miller: “We ask of you to secure to us American Anglo-Saxon civilization without contamination or adulteration with any other!”

The Chinese Exclusion Act banned Chinese laborers from entering the United States, and prohibited Chinese immigrants from becoming U.S. citizens. This act marked the first time in U.S. history that a federal law restricted a group from immigrating on the basis of race.

To enforce the Chinese Exclusion Act, the Angel Island Immigration Station was built in 1910. Deemed the “Guardian of the Western Gate,” Angel Island drew a striking contrast to the European immigration of Ellis Island. Over 70% of its detainees were Chinese; most were young men between 14-18 years of age.

Upon their arrival to Angel Island, Chinese migrants were segregated by gender, and separated from their children. They endured painstaking interrogations that required college-level studying for acceptable entry. Migrants had to memorize fastidious facts about their original Chinese households and lives. Some interrogations required over fifty pages of typed testimony.

Below are questions asked during these immigration tests:

- What direction did your doorway face?

- How many windows are in your house?

- How many steps are there to your front door?

- Of what material was the floor in your bedroom?

- How many times a year did you receive letters from your father?

- Who lived in the third house in the second row of houses in your village?

- Where was the rice bin located in your house?

- What day were you married?

- Was there music accompanying your marriage?

- Are you a polygamist?

Their living spaces were dark, cramped fire hazards housing detainees at 400% capacity. Ten windows and one ventilator for 140 men. Bathrooms were small and unsanitary. Many opted to leave their waste in bushes or at the stables, attracting flies and disease.

The Bureau of Immigration did not initially provide mattresses. The administration thought the migrants would not be used to sleeping on them. Detainees were given only a blanket and pillow.

Later, mattresses were added.

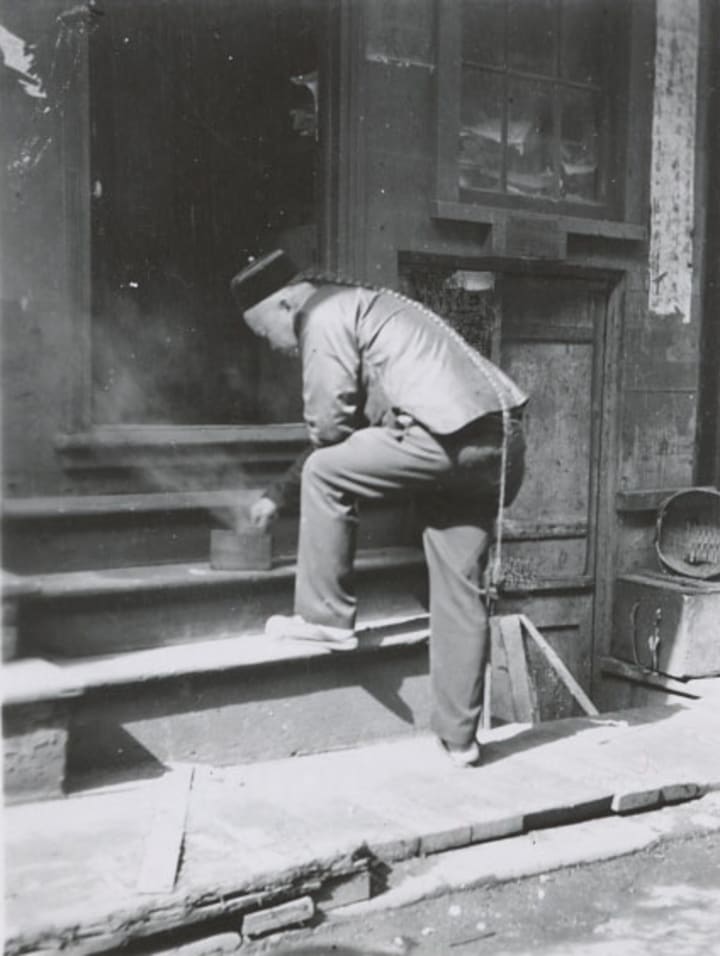

Before entering these crowded living spaces, the Chinese detainees endured an invasive, military-style medical inspection that required nude physical exams and the humiliating inspection of body parts. All Asian detainees were forced to submit stool samples into wash basins. Physicians would strip groups of detainees and expose them to the chilly sea breeze for several hours.

The hospital lacked fire prevention measures, evacuation plans, and a psychiatric ward. The clinic had dangerous sanitation issues, hot water shortages, poor air circulation, an insufficient number of hospital staff, and vermin infestations.

Abysmal safety regulations did not stop medical authorities from treating foreign detainees like stench and vermin. White employees experienced the island as a cultivated space of leisure. Chinese migrants experienced the island as a dehumanizing prison.

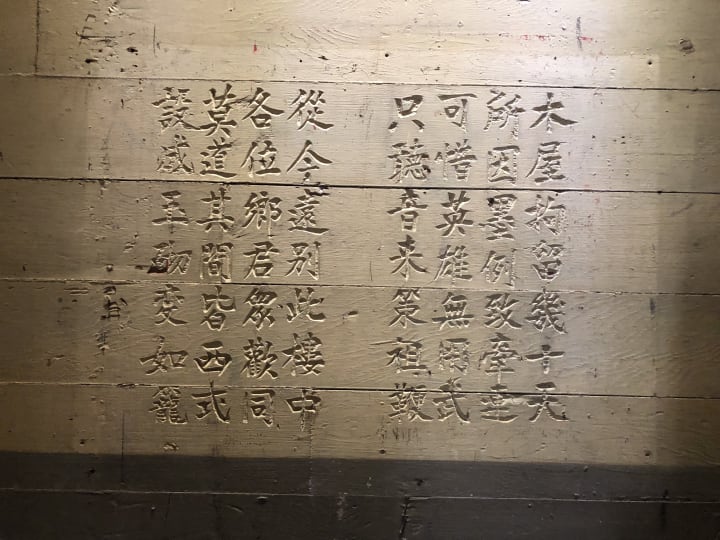

To protest their discriminatory treatment, Chinese detainees carved and painted poetry on the barrack walls. Most of their poems followed classical Chinese poetic forms with even numbers of lines: four, five, or seven characters per line; and every other two lines in rhyme. The content paints a somber picture: travels to the United States, containment in the facilities, bleeding anguish, catatonic loneliness, and fervent self-determination.

Example Poem #1

Imprisoned in the wooden building day after day,

My freedom withheld; how can I bear to talk about it?

I look to see who is happy, but they only sit quietly.

I am anxious and depressed and cannot fall asleep.

The days are long and the bottle constantly empty;

My sad mood, even so, is not dispelled.

Nights are long and the pillow cold; who can pity my loneliness?

After experiencing such loneliness and sorrow,

Why not just return home and learn to plow the fields?

Immigration Commissioner Hart Hyatt North, who initially supervised the station, ordered the “graffiti” on walls to be filled with putty and painted over — the detainees continued to decorate their holding cells with their words. As the paint cracked over time, the crumbling putty revealed layers of poetry underneath. As if the walls were apologizing for not having the strength to collapse.

These surviving works built a community across time and space. Their courageous carvings motivate efforts to combat discrimination and create a more just society. As coalitions of Asian Americans act in solidarity to these stories of endurance, they build resilience against oppressive xenophobia.

Despite suffering through racist travel restrictions, forced incarceration, and indefinite detention, these migrants hoped their trails of tears would not be lost on future generations.

When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the U.S. and China became allies against a common enemy. To encourage enlistment, Congress passed a law in 1942 that offered swift naturalization to Chinese-born service members. Close to 20,000 Chinese Americans enlisted in the armed forces. The mass mobilization of troops caused labor shortages at home. For the first time, Chinese men and women were hired for technical, professional, and clerical positions.

As China became an ally during the war, the United States could no longer defend Chinese exclusion. Angel Island closed operations in 1940 and the Chinese Exclusion Act was voted down by Congress in 1943.

“The admission of Oriental immigrants who cannot be amalgamated with our people has been made the subject either of prohibitory clauses in our treaties and statutes or of strict administrative regulations secured by diplomatic negotiations. I sincerely hope that we may continue to minimize the evils likely to arise from such immigration without unnecessary friction and by mutual concessions between self-respecting governments.”

President William Howard Taft, Inaugural Address, March 4, 1909

I highly recommend visiting Angel Island in the San Francisco Bay Area. Visitors walk through memorialized detention centers and witness its living conditions and poetry. The experience was humbling, heart-wrenching, and hopeful. Walking amongst those walls gives greater context and humanity to the issues of immigrant detention centers today.

For more Angel Island Wall Poetry, click here.

Example Poem #2

This is a message to those who live here not to worry excessively.

Instead, you must cast your idle worries to the flowing stream.

Experiencing a little ordeal is not hardship.

Napoleon was once a prisoner on an island.

About the Creator

DJ Nuclear Winter

"Whenever a person vividly recounts their adventure into art, my soul itches to uncover their interdimensional travels" - Pain By Numbers

"I leave no stoned unturned and no bird unstoned" - The Sabrina Carpenter Slowburn

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.