The Phantom Time Hypothesis: Did the Middle Ages Never Happen?

History

The Phantom Time Hypothesis: Did the Middle Ages Never Happen?

Introduction: What Is the Phantom Time Hypothesis?

Imagine if 300 years of history, as we know it, simply never occurred. That’s the claim at the heart of the Phantom Time Hypothesis, a bold and controversial theory suggesting that parts of the Middle Ages—from approximately 614 to 911 AD—were invented by those in power. Originally proposed by German historian Heribert Illig in the 1990s, this theory has fascinated conspiracy theorists and history buffs alike, sparking endless debates and speculation. Could it be true that our historical timeline is off by centuries? In this article, we’ll dive into the theory’s background, evidence, and counterarguments, examining whether the “phantom time” really exists.

The Origins of the Phantom Time Hypothesis

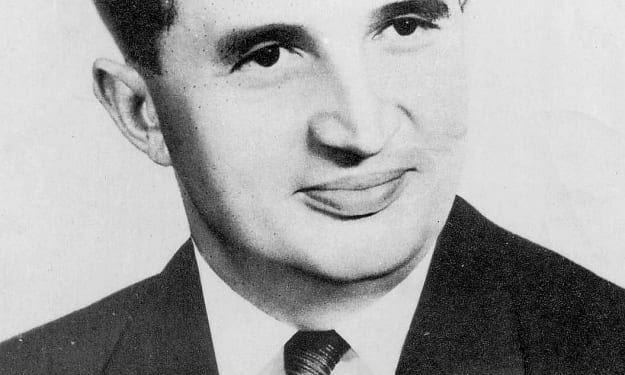

Heribert Illig: The Man Behind the Theory

Heribert Illig, a German historian and writer, first introduced the Phantom Time Hypothesis in 1991. Illig believed that roughly 297 years of medieval history were fabricated, and that the calendar was deliberately altered to create these “phantom” years. According to Illig, this conspiracy was orchestrated to align the Christian calendar with significant events and to reinforce certain political and religious narratives of the time.

The Timeline in Question: 614 to 911 AD

Illig’s theory focuses on the years between 614 and 911 AD, a period that encompasses part of the Early Middle Ages. He argues that historical records from these centuries are either sparse, inconsistent, or fabricated. The reasons for this “phantom time,” according to Illig, relate to a few key figures, particularly Holy Roman Emperor Otto III and Pope Sylvester II, who supposedly wanted to create a historical timeline that placed them at the dawn of the first millennium.

The Motivation Behind the Phantom Time Hypothesis

The Role of Otto III and Pope Sylvester II

One of the most intriguing aspects of the Phantom Time Hypothesis is the role of Otto III, who ruled the Holy Roman Empire from 996 to 1002 AD. Illig suggests that Otto III and Pope Sylvester II conspired to change the calendar, adding nearly 300 years to make the year 1000 seem more significant. By fabricating historical events and aligning the timeline to create a “new” year 1000, they sought to legitimize their rule and highlight the Christian faith’s supremacy during a symbolic period.

Calendar Changes and Power Dynamics

Illig’s theory posits that altering the calendar was a way to strengthen political and religious power. If Otto III could “jump” the timeline forward, he could center his rule in the year 1000, a date with substantial religious and cultural importance, aligning with apocalyptic prophecies and millennial beliefs that were prominent at the time. In this way, time itself was molded as a tool to solidify power, influence perceptions, and enhance the legitimacy of the empire.

Evidence Supporting the Phantom Time Hypothesis

The Julian and Gregorian Calendar Discrepancies

A central element of Illig’s theory lies in the discrepancies between the Julian and Gregorian calendars. When Pope Gregory XIII introduced the Gregorian calendar reform in 1582, it adjusted the calendar by 10 days to realign it with the solar year. According to Illig, if nearly 300 years of history were indeed fabricated, then only a correction of 7–8 days would have been necessary, not 10 days. This “excessive” adjustment, in Illig's view, hints at the possibility of phantom time being added to history.

Lack of Physical Evidence from the Early Middle Ages

Illig also points to a supposed lack of physical and archaeological evidence from the 7th to the 10th centuries. Structures, artifacts, and cultural relics that would typically support historical accounts from this period appear sparse. For instance, some of Europe’s oldest architectural structures and artifacts can be dated before or after the supposed “phantom time” but are curiously absent during these particular centuries. According to Illig, this absence suggests that these years might have been fabricated.

Inconsistent Historical Records

Another argument Illig raises is the inconsistency in historical records. He suggests that historical documentation from the “phantom” period lacks coherence and consistency, with major events seemingly poorly recorded or lacking detail. For example, he argues that the Carolingian Empire, which supposedly existed during this period, has significant gaps in its historical record. Additionally, some documents and texts from this era were not well preserved, which Illig believes adds to the theory that these centuries were manufactured.

Counterarguments: Why Most Historians Reject the Phantom Time Hypothesis

The Abundance of Corroborating Evidence

Most historians quickly dismiss the Phantom Time Hypothesis due to the abundance of corroborating evidence from outside Europe that supports a continuous timeline. Events and artifacts from cultures across Asia, the Middle East, and the Americas align chronologically with the Early Middle Ages in Europe. Records of astronomical events, such as eclipses and comets, which can be reliably dated, also align with the accepted timeline, making it unlikely that hundreds of years were simply added.

Archaeological Finds and Dated Artifacts

Archaeological discoveries from the period in question provide further evidence against the theory. Artifacts and structures from the 7th to the 10th centuries exist across Europe, showing clear developmental progress over time. From remnants of early medieval towns to religious artifacts, these items are well-documented and have been carbon-dated to the period Illig claims never happened. Historians argue that if nearly three centuries were missing, these objects would not exist in such abundance.

The Complexities of Calendar Reform

The Julian calendar reform in 46 BC and the later Gregorian reform in 1582 were both responses to inaccuracies in timekeeping but do not inherently indicate that years were added. Calendar adjustments account for the difference in solar year calculations, and the 10-day correction was necessary to compensate for centuries of gradual drift. According to historians, Illig’s argument ignores the natural need for calendar adjustments over long periods due to astronomical differences, rather than supporting phantom years.

The Legacy of the Phantom Time Hypothesis

A Fascinating Thought Experiment

Despite its rejection by mainstream historians, the Phantom Time Hypothesis remains an intriguing thought experiment. It challenges us to think critically about the nature of history, timekeeping, and how historical records are compiled and maintained. The hypothesis has inspired many to question accepted historical narratives and to examine how power dynamics and human motives can shape our understanding of the past.

Conspiracy Theories and Public Fascination

The Phantom Time Hypothesis has gained a significant following among conspiracy theorists and has permeated popular culture. It exemplifies how a single theory can spark public interest and challenge our assumptions about history, even if it lacks solid evidence. The idea that parts of history could be manufactured taps into a broader fascination with conspiracy theories, appealing to those who question official narratives and remain skeptical of historical records.

Conclusion: Did the Middle Ages Really Happen?

While the Phantom Time Hypothesis is a captivating theory, the vast majority of historians and archaeologists agree that it lacks substantial evidence. Physical artifacts, dated records from multiple civilizations, and the natural progression of timekeeping practices refute the idea that 297 years of history were fabricated. Although it’s tempting to entertain the notion that time itself could be manipulated, the weight of historical and archaeological evidence strongly supports the authenticity of the Middle Ages.

The Phantom Time Hypothesis serves as a reminder of how our understanding of history can be challenged and shaped by unconventional theories. It prompts us to consider how history is recorded and the trust we place in historical timelines. While the theory may not hold up to scientific scrutiny, it will likely continue to captivate imaginations and provoke questions about the mysteries of our past.

FAQs

1. What exactly is the Phantom Time Hypothesis?

The Phantom Time Hypothesis is a theory that proposes nearly 300 years of the Early Middle Ages, specifically from 614 to 911 AD, were fabricated, and that these years never actually occurred.

2. Why do some believe the Middle Ages were fabricated?

Proponents of the hypothesis argue that powerful figures, like Holy Roman Emperor Otto III and Pope Sylvester II, added phantom years to the timeline to align with significant events and give legitimacy to their rule in the symbolic year 1000.

3. How do historians disprove the Phantom Time Hypothesis?

Historians point to consistent records from other civilizations, such as in the Middle East and Asia, as well as astronomical data and archaeological finds that align with the timeline, disproving the idea of missing centuries.

4. What role does the Gregorian calendar play in this theory?

Illig claims that the 10-day correction in the Gregorian calendar reform suggests extra time was added, but historians clarify that this adjustment was necessary due to natural calendar drift over centuries, not because years were fabricated.

5. Is there any evidence supporting the Phantom Time Hypothesis?

While Illig and supporters point to sparse records and inconsistencies in European history from this period, the lack of substantial evidence, combined with corroborating data from various sources, makes the hypothesis widely unaccepted among experts.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.