The mysterious Ajie drum in Tibet, China

The "Ajie drum" sounds very beautiful, especially when it is associated with the legend of a beautiful girl. But when you know that this drum is made of human skin, is it still so beautiful? There is a human bone flute that can play extremely beautiful music, but do you know what it is made of? As the name suggests, the human bone flute is made of human leg bones. Isn't it cruel? This "skinning" torture is more cruel than lingchi, as it requires intact skin rather than fragmented flesh.

In traditional Tibetan culture, the Ajie drum means a drum made of a girl's skin, that is, a human skin drum. Legend has it that the sound of the Ajie drum can connect life and death and transcend reincarnation. This drum is also used to worship gods, so the production requirements are very strict. The human skin must be selected from a girl who has not experienced love, so that it is the purest. If it is a mute, it is even better, because a mute does not lie and the soul is not tainted. And it must be skinned alive, so that the sound of the human skin drum is the best. When they meet a suitable girl who is not mute, their tongues will be cut off and their leg bones will be made into drumsticks.

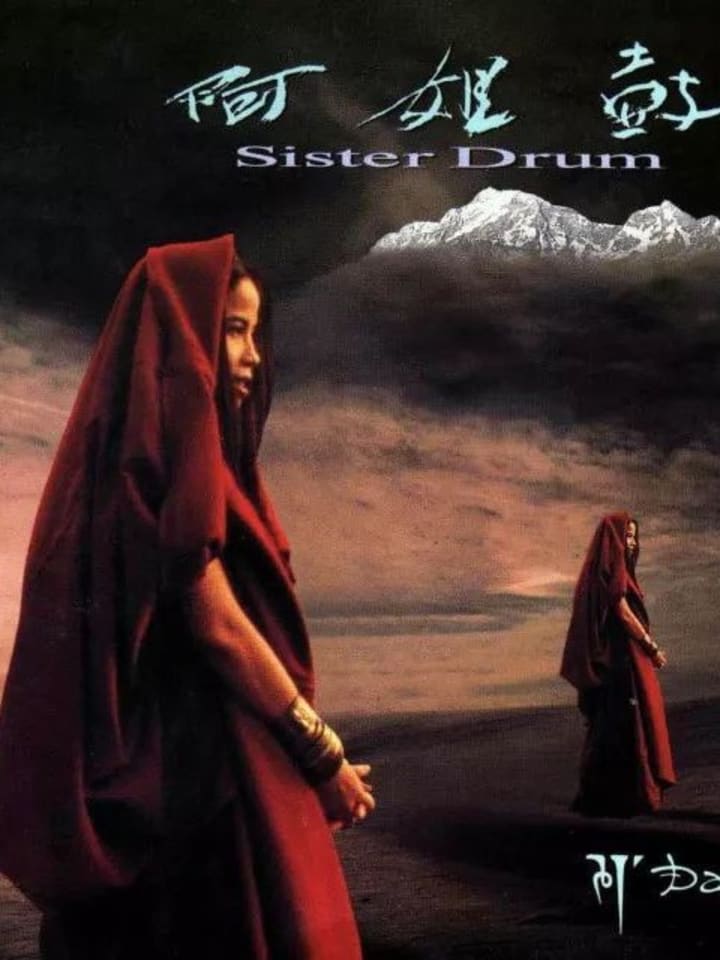

The song "Ajie Gu" written by Zhu Zheqin and He Xuntian describes a younger sister's search for her mute sister, who turned out to have been chosen and made into a human-skin drum. The lyrics in the song go, "I've always thought of my sister as old as me, and suddenly I understood her, and from then on I kept looking for her every day. There were drum sounds coming from the horizon, and that was my sister talking to me. Um Mani Padme Um Mani Padme." The tune is low and chilling. This is a story the singer heard from his parents when he went to Tibet. After hearing this story, he was shocked. So he created this song to tell this story to future generations. It is said that the mute sister in the lyrics was also willing to be made into a drum, but whether it was voluntary or not is a matter of debate.

In fact, skinning was also a form of torture in the former Tibet, and there are still many religious sacrifices in the Tibetan area. Many people even think that it is an honor to sacrifice to religion, but in fact, the people who are chosen have no right to refuse. Just like the mute girl in the Ajie drum, does she have the right to refuse? She can't even say goodbye to her family. Some people may think that such a cruel thing should be fake. In fact, there are human skin drums, human bone drumsticks and bowls made of human skulls in museums in Qinghai, Tibet and other regions.

The production of these things seems absolutely cruel and inhumane now, but at that time it was a sacrificial style that everyone accepted. It is impossible to judge whether it is right or wrong from today's perspective.The Keeper of EchoesThe drum hung in the prayer hall, its yak-skin surface worn smooth by centuries of fingertips. Lhamo traced the Tibetan characters carved into its rim—A-Che Dagu, Sister Drum. Old Tenzin claimed it sang with the voice of a girl sacrificed during the Qing dynasty, her skin stretched over the frame to atone for her village's sins. Foreign scholars dismissed this as macabre folklore, but Lhamo knew better.

She’d heard the weeping at midnight.

When the Beijing anthropologist arrived with infrared cameras, Lhamo warned him: "Some stories breathe." Dr. Wu smiled, adjusting his glasses. "Superstition fades beneath science."

They set up equipment as snow blurred the Himalayan peaks. At 2:17 AM, the drum pulsed like a heartbeat. Dr. Wu’s screens flickered with thermal signatures—a child-sized figure kneeling before the drum. The audio recorder captured a girl’s voice humming Om Mani Padme Hum.

"Residual energy," Dr. Wu muttered, fingers trembling. "Explainable."

But Lhamo saw the frost blooming across the drumhead where no ghostly hands touched it. She remembered Grandmother’s warning: The drum isn’t haunted—it’s hungry.

On the third night, Dr. Wu approached the altar alone. Lhamo found him at dawn, paralyzed, staring at the drum now bearing fresh etchments—a name (Yangchen) and date (1796-1809) glowing silver as moonlight. His camera footage showed him tracing the characters, then screaming as his hand sank into the drum like quicksand.

The monastery’s oldest lama examined the new markings. "You woke the bridgekeeper," he sighed. "This drum doesn’t trap souls—it guides them. Yangchen volunteered her body to become this passage between worlds. Now you’ve torn the veil."

That evening, Lhamo performed the ritual Grandmother taught her: barley wine sprinkled on the drumhead, juniper smoke curling around the beam where Yangchen’s braid still hung knotted to the wood. The weeping softened into laughter.

Dr. Wu left at sunrise, abandoning his equipment. Lhamo watched him shuffle down the mountain path, right sleeve hanging empty.

Now when pilgrims ask about the drum’s whispers, she smiles. "Not a ghost story," she says, polishing the ancient frame. "A love letter."

The frost never returned.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.