The Movies That Shaped My Soul: How Five Stories Redefined What Cinema Could Feel Like

Behind every timeless frame—an actor’s unscripted line, a fight fought too real, a tear that wasn’t in the script—are the moments that taught me what humanity on film truly means.

Cinema doesn’t evolve in a straight line. It lurches forward when a film arrives that audiences can’t stop quoting, critics can’t stop arguing about, and other filmmakers can’t stop studying. These movies don’t just make money; they reset expectations for what stories can do, how images can move us, and where performance can go. They alter careers, reshape genres, and even tweak the way studios greenlight projects.

The five titles below—Good Will Hunting, Gladiator, the Indiana Jones series, the Rocky and Rambo sagas, and Goodfellas—did exactly that. Together they revitalized the character drama, resurrected the sword-and-sandals epic, redefined adventure grammar, made underdog grit a global export, and reinvented the gangster movie. Along the way, each production generated behind-the-scenes lore that’s nearly as famous as what made the final cut. From a therapeutic monologue that became a generational balm to a “hidden” studio-trolling scene in an Oscar-winning script; from a sand-choked production that felt like marching an army across history to a dangerous bout that sent its star to the hospital; from dysentery forcing a legendary last-second rewrite to improv that turned a tense set into an immortal meme—these films changed movies because the people making them took risks.

Below is how they did it—and why they still matter.

Good Will Hunting: When Vulnerability Became a Box-Office Superpower

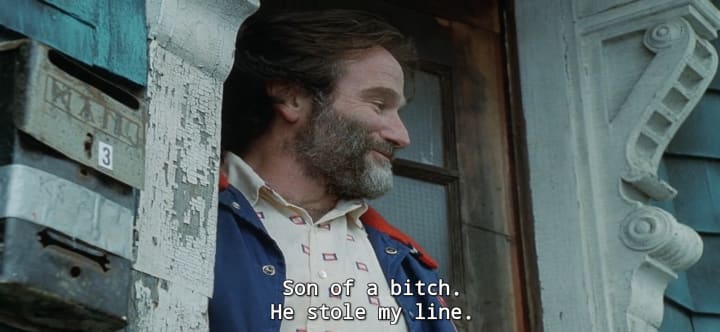

Hollywood in the late 1990s didn’t treat blue-collar brilliance and therapy as multiplex catnip. Good Will Hunting did. The story of a South Boston janitor with a genius-level mind and a scar-tough heart fused intellectual stakes with emotional catharsis, and audiences leaned in. Its power is anchored by Robin Williams’ performance as Sean Maguire—world-weary, wounded, and quietly fierce. Williams locates the movie’s pulse: that love is a skill you practice and grief is a landscape you learn to navigate.

In the park-bench scene, Sean punctures Will’s bravado not with volume but with care, and the line that many carry around like a kindness they once needed still lands with a soft thud of truth:

“You’re not perfect, sport, and let me save you the suspense—this girl you met isn’t either.”

The campus-to-couch arc reframed what a commercial drama could be. Instead of the frantic plot turns studios favored, Good Will Hunting trusted small rooms and big honesty. That trust paid off: it launched Matt Damon and Ben Affleck as A-list storytellers, returned Williams to dramatic glory, and convinced an entire cohort of execs that authenticity, not cynicism, could drive a hit.

Behind the scenes, the legends are part of its oxygen. Damon and Affleck famously planted a “hidden” scene to test whether execs were actually reading—the prank worked, the note arrived, and the duo learned how to protect their story. And the way the film closes, with Sean reclaiming his own life after helping Will choose his—there’s a wink that doubles as healing:

“He stole my line.”

What changed the industry? A studio movie proved that a therapy room could be a thrill ride if the stakes were human enough. It also cemented the notion that actors could sell original screenplays—an echo you can hear in later auteur-driven star vehicles.

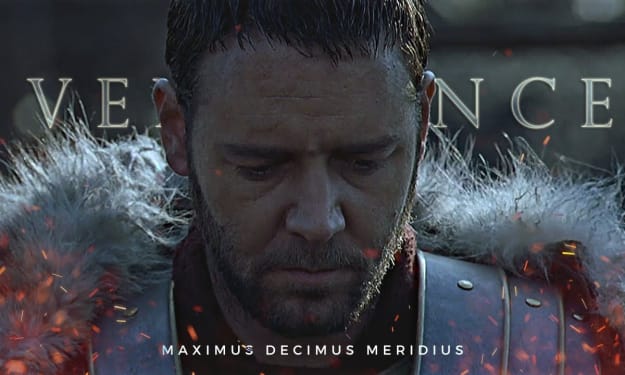

Gladiator: Reviving the Epic With Grit, Grain, and Blood

By 2000, the sword-and-sandals epic was considered a relic of Technicolor yesteryear. Then Gladiator rode in with dust in its lungs, real steel in its hands, and a hero forged from grief. Ridley Scott’s film didn’t just revive the genre; it modernized it. You feel the weight of armor, smell the torches, and sense the stadium’s hunger. The film’s texture—gritty cinematography, staccato battle editing, Hans Zimmer and Lisa Gerrard’s mournful score—reset expectations for historical spectacle.

When Maximus steps into the arena and detonates the crowd’s bloodlust into a question that ricochets through the cheap seats of history, the movie announces its modern swagger:

“Are you not entertained?”

The production was famously massive: armies of extras, practical sets the size of neighborhoods, and location work that turned logistics into art. Authenticity wasn’t an accessory; it was a thesis. Scott and his team threaded the needle between myth and history, populating the world with names and echoes from Rome’s annals. Discussion still swirls around Maximus’ spiritual kinship to real figures—most notably Marcus Nonius Macrinus—underscoring how the character feels plausible in Rome’s blood-stitched tapestry even as the specifics are fictional.

If the 1960s gave us the operatic pomp of Ben-Hur, Gladiator gave us battle-cam grime and political paranoia. It proved epics could be intimate, with character close-ups and battlefield chaos coexisting. And at the center, a soldier’s creed that has outlived memes and midnights, a line fans borrow for graduations, funerals, and difficult Mondays:

“What we do in life echoes in eternity.”

Behind the curtain, the movie’s scale was a miracle of coordination—rewrites during the shoot, on-set problem-solving, and a star who played through injuries. It’s easy to be roused by speeches; it’s harder to stage a crowd scene that looks like a living organism. Gladiator did both, and that’s why it endures.

Indiana Jones: The Blueprint for Adventure—Survival, Sweat, and Serendipity

Action before Raiders of the Lost Ark often meant competent spectacle. After Raiders—and its sequels—the standard became kinetic clarity, tactile peril, and character comedy welded to stunt craft. The Indiana Jones series didn’t just entertain; it wrote the grammar for how adventure should feel.

Take the truck chase in Raiders. You can diagram its geography on a napkin. Every gag is a setup with a payoff, every beat clarified with camera placement that respects the audience’s brain. It’s “readable action”: you always know where Indy is, what he wants, and what could break. That readability is why the set piece still teaches film classes.

And the lore? Legendary. Harrison Ford’s food poisoning in Tunisia forced a change to a bazaar duel; too sick for a prolonged fight, he suggested that Indy simply draw and shoot. The deadpan shot became one of cinema’s happiest accidents—and perfectly in character for a hero who saves wit for when the whip won’t do.

The films balance wonder with warning. In the Ark’s climactic unveiling, Spielberg stages awe as a moral hazard—beauty you must not own, only respect. Indy’s command to Marion is as much a rule for audiences as it is for survival:

“Don’t look at it, Marion! Keep your eyes shut!”

But the series’ soul is also in its rueful humor, the line fans quote when their knees pop on the stairs or when the day runs longer than the map promised:

“It’s not the years, honey, it’s the mileage.”

The franchise gave birth to a tone other series still chase: a hero who’s fallible, funny, and surprisingly tender; a world teeming with danger but governed by a clean moral compass; and set pieces that feel like puzzles solved at a sprint. Without Indiana Jones, modern action-adventure—from globe-trotting treasure hunters to booby-trapped heists—would look and cut differently.

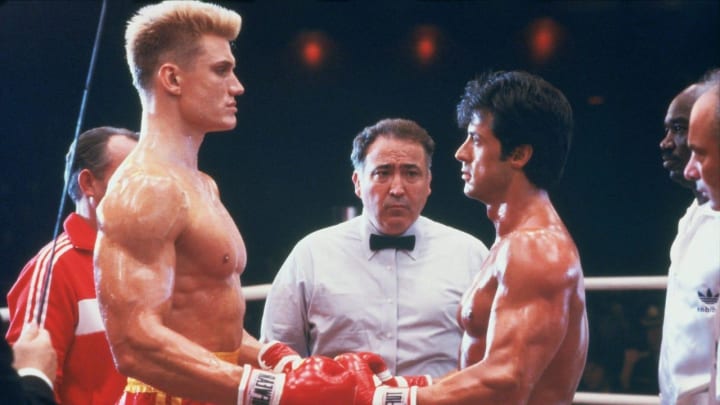

Rocky and Rambo: Two Sides of American Grit

Few artists have birthed two mythologies that speak to such different parts of a nation’s psyche. With Rocky, Sylvester Stallone enshrined the working-class striver who turns humiliation into endurance. With Rambo, he distilled a meditation on trauma, alienation, and the violence America exports and imports.

Rocky changed the film landscape by proving that sentiment, sincerity, and sweat could beat cynicism at the box office. Stallone famously wrote the script in a burst, refused to sell unless he could star, and then delivered a performance that turned a nobody into an everyman saint. The movie’s training montage grammar—legs churning, steps pounding, cuts accelerating—is now athletic film language 101. And when fans need a north star for resilience, they reach for the speech that’s become an all-purpose anthem for hard seasons:

“It ain’t about how hard you hit. It’s about how hard you can get hit and keep moving forward.”

The series kept finding new gears. Rocky IV fused Cold War pageantry with pop-video aesthetics; in chasing realism, Dolph Lundgren’s punches sent Stallone to the ICU. The price of “movie real” was, for a day, terrifyingly real.

Flip the coin and you get First Blood, a thriller about a damaged veteran cornered by small-town hostility. It’s sensitive and prickly, more elegy than explosion. Later sequels scaled up the spectacle, but the DNA remained a critique wrapped in catharsis: what do we ask of warriors, and what do we give them back? Rambo’s mantra—half warning, half survival manual—summarized the franchise’s steel-eyed stare at violence:

“To survive a war, you gotta become war.”

These series changed the business by proving that personal authorship could power franchises, that physicality could be poetry, and that fight choreography could feel like character development, not just combat. They also seeded a fitness and training montage culture that migrated into sports docs and even reality TV. When a camera watches someone try, Rocky is in the room.

Goodfellas: Velocity, Voiceover, and the Seduction of Sin

Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas didn’t just update the gangster picture; it detonated it. The film’s propulsive style—needle-drops that feel like arterial sprays, tracking shots that invite you into the bloodstream of the mob, voiceover that seduces and damns—became the new template for crime storytelling. It’s the rare film whose technique is as quotable as its dialogue.

The Copacabana steadicam glide is a welcome-to-the-life seduction; the frenetic cocaine-paranoia final act is a you-can-never-leave hangover. Together they map the emotional arc of criminal glamour to criminal rot. The movie marries docu-texture detail (food, clothes, cars, rituals) with a Shakespearean arc of loyalty curdling into betrayal.

And then there’s the table-side ritual that turns an offhand tease into a threat, a scene born from improvisation and polished in the edit bay until it gleams like a razor:

“I’m funny how, I mean funny like I’m a clown, I amuse you?”

From the first frame, the film’s thesis sings through Henry Hill’s memory—ambition as fate, seduction as doom. His opening confession became the movie’s calling card, the one-liner that explains the addiction better than any sermon:

“As far back as I can remember, I always wanted to be a gangster.”

What changed after Goodfellas? Everything from prestige TV to music videos absorbed its rhythm. Crime stories became faster, darker, and more self-aware. The movie also proved that moral clarity could coexist with stylistic seduction. You can be thrilled by the ride and still feel the ruin.

Why These Five Still Matter

Together, these films form a syllabus in how cinema evolves. Good Will Hunting insisted that tenderness is dramatic. Gladiator reclaimed scale with soul. Indiana Jones perfected the readable set piece and the charming stumble. Rocky and Rambo split the atom of American grit into triumph and trauma. Goodfellas married adrenaline to moral accounting. Each changed what audiences expected and what studios gambled on.

Their behind-the-scenes film legends aren’t just trivia; they’re proof that risk, constraint, and improvisation are part of cinema’s engine. A sick star suggests a shortcut and accidentally writes a classic joke. Two hungry writers insert a booby trap into their script and learn who’s paying attention. A director corrals armies, sandstorms, rewrites, and history itself to resuscitate a supposedly dead genre. A boxer’s body takes a real hit so an audience can feel a fake one. An improv lands like a punch and becomes the scene everyone quotes at parties.

Movies change the landscape when the people making them are brave enough to change themselves—by trusting silence, embracing mess, or pointing the camera closer than comfort. That’s why these five aren’t just great. They’re landmarks.

References (APA)

Good Will Hunting

Van Sant, G. (Director). (1997). Good Will Hunting [Film]. Miramax.

Damon, M., & Affleck, B. (1997). Good Will Hunting: A Screenplay. Miramax Books.

Nanos, J. (2013, December). An oral history of Good Will Hunting. Boston Magazine.

Travers, P. (1997, December). Good Will Hunting review. Rolling Stone.

Gladiator

Scott, R. (Director). (2000). Gladiator [Film]. DreamWorks/Universal.

Landau, D. (2000). Gladiator: The Making of the Ridley Scott Epic. Newmarket Press.

Povoledo, E. (2008, October 16). Tomb of Roman general is found in Italy. The New York Times.

Fraser, P. M. (2005). The Roman World (select essays on imperial military culture). Oxford University Press.

Indiana Jones Series

Spielberg, S. (Director). (1981–2008). Indiana Jones series [Films]. Lucasfilm/Paramount.

Rinzler, J. W. (2008). The Complete Making of Indiana Jones: The Definitive Story Behind All Four Films. Del Rey.

Bouzereau, L. (Director). (2003). Indiana Jones: Making the Trilogy [Documentary]. Lucasfilm.

McBride, J. (2012). Steven Spielberg: A Biography (Updated ed.). University Press of Mississippi.

Rocky and Rambo

Avildsen, J. G. (Director). (1976). Rocky [Film]. United Artists.

Stallone, S. (Director). (1985). Rocky IV [Film]. MGM/UA.

Johnson, D. W. (Director). (2020). 40 Years of Rocky: The Birth of a Classic [Documentary]. Cinema 83.

Kotcheff, T. (Director). (1982). First Blood [Film]. Carolco/Orion.

Morrell, D. (1972). First Blood. David R. Godine.

Goodfellas

Scorsese, M. (Director). (1990). Goodfellas [Film]. Warner Bros.

Pileggi, N. (1985). Wiseguy. Simon & Schuster.

Kenny, G. (2020). Made Men: The Story of Goodfellas. Hanover Square Press.

Ebert, R. (1990, September). Goodfellas review. Chicago Sun-Times.

About the Creator

Flip The Movie Script

Writer at FlipTheMovieScript.com. I uncover hidden Hollywood facts, behind-the-scenes stories, and surprising history that sparks curiosity and conversation.

Comments (1)

Thank you for sharing!