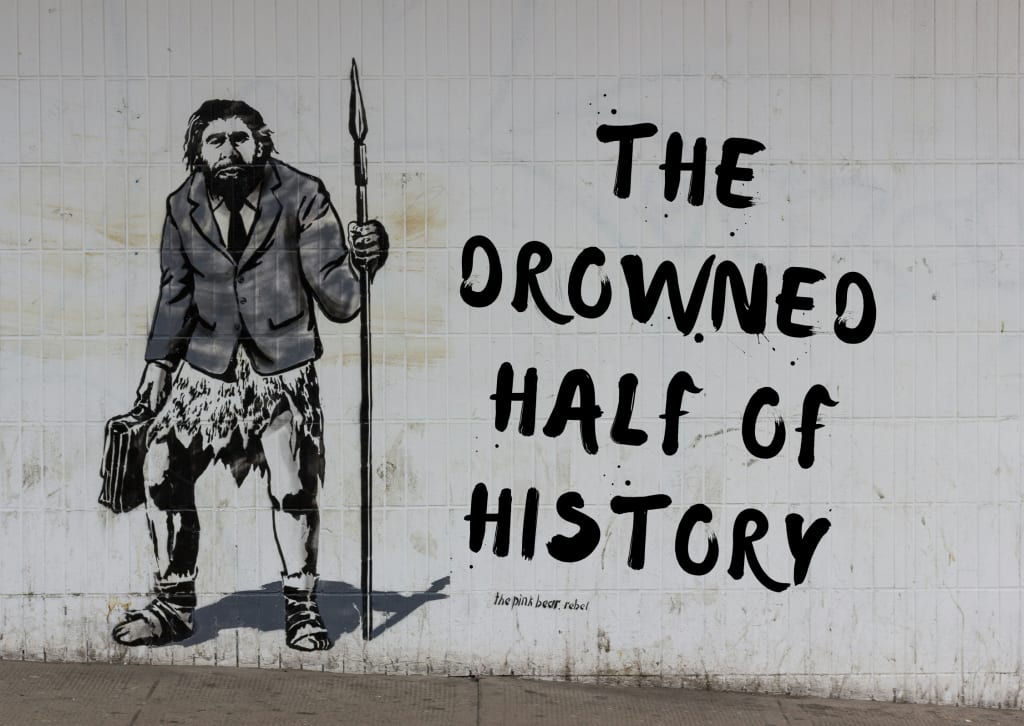

The Drowned Half of History

Why So Much of Our Ice Age Story Is Now Underwater

Since the last Ice Age, the sea has risen more than 120 metres—enough water to drown cities, erase river valleys, and hide a whole extra ring of coastlines around the continents.

Around 50,000 years ago, during a cold interval geologists call Marine Isotope Stage 3, global sea level sat tens of metres lower than at present—on the order of 30 to 60 metres down. So much water was locked up in northern ice sheets that the ocean had pulled back from today’s coasts, exposing the continental shelves as broad lowlands. River mouths lay far out on what is now seabed. Bays were grasslands, shoals were dry ground. Many “coastal” camps of that age would sit today under 20, 40, even 70 metres of water.

Gibraltar is one of the clearest examples. Neanderthals lived for tens of thousands of years in caves on the east face of the Rock, caves that now open almost directly onto the Mediterranean. When they first used Gorham’s Cave, however, the entrance was not a sea cliff. A sandy coastal plain stretched up to five kilometres out from the foot of the Rock: dunes, low wetlands, freshwater springs, and a shoreline far to the east. Herd animals would have moved across that plain. Sea birds would have nested on the dunes. Neanderthals could have walked out onto open ground where a modern diver now floats in blue water. That entire hunting ground is now underwater. Modern surveys on the submerged shelf have found freshwater sources and rock outcrops that would have mattered to toolmakers—a drowned resource landscape we can only sample through cores and dives.

The same pattern appears elsewhere. In the North Sea, a low-lying region known as Doggerland once connected Britain to continental Europe. It held rivers, wetlands, and coasts used by hunter-gatherers in the early Holocene. Forests and marshes grew where ferries now cross deep channels. As the ice sheets melted, rising seas turned Doggerland into a scatter of islands and then erased it altogether. Trawlers and underwater archaeologists still recover stone tools, animal bones, and peat from its former surface, reminders that we are skimming the edges of a much larger submerged archive, glimpsing a country that is gone from any modern map.

Around 50,000 years ago, those shelves were not just exposed; they were living through climate whiplash. The North Atlantic saw repeated episodes when vast numbers of icebergs broke away, freshening surface waters and disturbing ocean currents. Superimposed on that were abrupt warmings and slower coolings recorded in ice cores, swings that could shift storm tracks and sea ice limits within a few human lifetimes. To people on those coasts, the global sea level might have seemed stable over a lifetime, but the character of the shoreline was not. Harbours silted or scoured, winters bit deeper or eased, pack ice crept closer or pulled back. A family could stay in the same valley for generations and still feel the edge of the world changing around them.

The truly dramatic vertical rise came later, after the Last Glacial Maximum around 20,000 years ago, when global sea level climbed more than 120 metres in pulses as the great ice sheets collapsed. In some intervals, the shoreline would have marched inland by metres within a single lifetime, overtaking bogs, floodplains, then whole lowland forests. That final flooding drowned Doggerland and countless other plains for good, turning once-inland hills into islands and leaving only the higher ground we recognise as modern coasts.

The evidence is blunt: a large fraction of Pleistocene coasts—the places where humans and Neanderthals hunted, foraged, camped, and moved—now lies underwater. A few caves like those at Gibraltar, and a handful of submerged sites and dredged finds, give us brief windows into that missing world. The rest is still out on the continental shelves, under silt and salt. Our prehistory is built from what happened to stay on land. Whatever stories unfolded on those drowned shores are there in the dark, intact or broken, waiting in places we can hardly reach.

About the Creator

Richard Patrick Gage

I'm an author and publisher of poem anthology group from northern Ontario, I like enabling other voices and new writers. I'm also a novel writer, known for the indie darling Noetic Gravity that came out in June 2025. Here I write for me.

Comments (1)

I’ve had designs in the far back of my mind to write a historical fiction set in this era. Purely speculative obviously but I always thought there could be an interesting story and theme there