The Burial Mask of Pop Culture

The stories of the Egyptian mummies and their perception of the public

A mummy is generally understood as any corpse that has been remarkably preserved, and its story stretches across nearly every corner of the globe. But when it comes to monsters, it’s nearly impossible not to picture that iconic, linen-wrapped, upright figure.

So, why did the Egyptian mummy come to symbolize mummification? How did this ancient funerary tradition evolve into the shambling, silent, undead creature wrapped in linen that haunts our pop culture today?

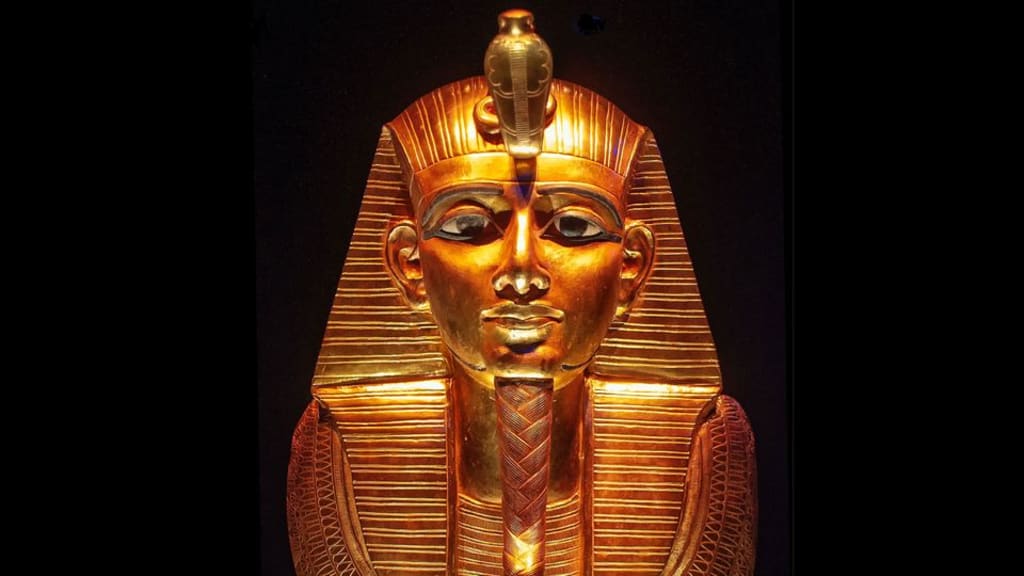

Mummification was not just a practice, but a sacred, transformative journey in ancient Egypt, intimately tied to the gods Isis and Osiris. This ritual was believed to prepare both the body and soul for the eternal afterlife. However, the mummy’s path into the realm of nightmares began long before it became a creature of horror. It started with the commercialization of Egyptian remains and a twist of linguistic confusion.

In early modern Asia and Greece, bitumen was used as a medical remedy. The Persian word for bitumen evolved into the Latin mumiya, which later became mummie in medieval Europe. And with this term came a dangerous misconception: that mummified bodies possessed the same medicinal qualities as bitumen. This sparked the rise of a gruesome trade, where human mummies were harvested and sold for use in pharmaceuticals.

By the 16th century, this controversial market flourished as people believed these ancient remains could cure ailments. One English merchant's unsettling account reveals just how far the trade went: John Sanderson wrote of breaking apart an Egyptian mummy, eager to see how its flesh was transformed into a supposed remedy.

He returned home with over 600 pounds of mummified remains, which were sold to London apothecaries. Some of these mummies were kept whole, with their bodies unwrapped for scientific study — further blurring the line between reverence and exploitation.

In 1763, at the request of the British Royal Society, John Hadley carefully unrolled a mummy in the comfort of his home. His meticulous documentation paved the way for the first systematic study of Egyptian mummy necropsies, later led by German physician Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in the late 1700s.

For centuries, ancient Egypt had captivated the imaginations of Europeans, but it was Napoleon's 1798–1801 invasion of Egypt that truly ignited a cultural firestorm. His conquest brought back a treasure trove of looted artifacts and firsthand accounts, sparking the birth of Egyptology—a discipline that would soon become a fascination of the masses.

This period marked the dawn of Egyptomania in the 19th century, a term used to describe the fervent public obsession with ancient Egyptian culture. By the early 1800s, ancient Egypt had firmly cemented itself as a fashionable pursuit, particularly in Britain. The British government even constructed an Egyptian Hall to house the spoils of Napoleon's surrender.

This hall became a showcase for the priceless artifacts and relics brought back from Egypt, and the public couldn't get enough of it. People eagerly snapped up cheap replicas of Egyptian furniture, china adorned with Egyptian motifs, and other commercial goods inspired by the exotic allure of the ancient world.

But it wasn't just artifacts that fueled the craze—the mummy itself was becoming a monster of mythic proportions. The 1820s saw a surge in the popularity of the mummy in both scientific and sensational circles. Giovanni Belzoni, a former circus strongman, recreated an Egyptian tomb in London's Piccadilly at the Egyptian Hall in 1821, drawing massive crowds.

His marketing genius went even further, as he staged public mummy autopsies, turning the ancient and sacred into a grotesque spectacle. The stage was set for the mummy to rise from its ancient tomb and become a fixture of both history and horror.

At times, Giovanni Belzoni was assisted by the surgeon and antiquarian Thomas Pettigrew, who would go on to become a renowned Egyptologist and celebrity mummy autopsist in the following decade. Pettigrew’s fame was solidified with the 1834 publication of his groundbreaking work, History of Egyptian Mummies, which is still regarded as the foundational text in the study of mummies.

In 1822, John-François Champollion made a monumental breakthrough, translating hieroglyphics for the first time using the Rosetta Stone. This achievement fueled an ever-growing desire to understand every facet of ancient Egyptian culture—including its afterlife. As the fascination with Egypt deepened, scholars and adventurers sought to identify the names and social statuses of mummies, considering it crucial to understanding their historical significance.

In 1825, Augustus Bozzi Granville conducted the first modern medical autopsy on a mummy, further entwining the ancient with the scientific. Mummies continued to make appearances in hospitals, artists' studios, dissection theaters, universities, and even the drawing rooms of the upper class. Unwrapping mummies was not only an academic endeavor but a public spectacle that combined intellectual pursuit with a form of morbid entertainment.

For those who couldn’t witness these gruesome exhibitions in person, newspapers satiated their curiosity with detailed accounts of the events. The public’s growing appetite for these displays underscored the transformation of the mummified corpse from a sacred object of reverence to an item of entertainment.

The treatment of mummies as objects to be unwrapped and studied highlights the dark, commodified fascination that has long surrounded them. Understanding this transformation is key to unraveling the complex legacy of the mummy in popular culture.

Mummies became unsettling symbols of culture, history, and identity—tangible representations that fiction would soon transform into monsters. Jane Loudon was the first to weave these tensions into a fictional narrative.

In her 1827 science fiction novel, The Mummy! Or A Tale of the Twenty-Second Century, she introduces the story of an animated Egyptian mummy. Throughout the strange and eerie tale, the Mummy Cheops emerges as a horrifying yet instructive undead figure. The novel was a massive commercial success, reprinted multiple times, and helped cement the mummy’s place in both literature and popular culture.

The influence of imperialism played a significant role in the commodification and fetishization of the mummy in Britain. Colonial conquests around the globe provided museums and private collectors with an endless supply of exotic artifacts—and bodies. By mid-century, unwrapping mummies had become a meticulously rehearsed spectacle, almost formulaic in its execution.

The body would be displayed among Egyptian relics and funerary objects, creating a macabre atmosphere. Lectures about mummification and ancient Egyptian history served as the prelude to the main event: the dramatic unveiling of the mummy’s textiles and body parts.

The audience was encouraged to engage directly with the relics—passing around amulets, fragments of bandages, even pieces of bone. Some would touch, smell, or even taste these items, deepening the sense of intimacy and eerie fascination. At private unwrapping parties, guests might even keep the objects as morbid souvenirs, a tangible connection to the dead.

This chilling blend of academic curiosity and voyeuristic entertainment cemented the mummy’s place as both an object of study and a terrifying symbol in the cultural imagination.

About the Creator

ADIR SEGAL

The realms of creation and the unknown have always interested me, and I tend to incorporate the fictional aspects and their findings into my works.

Comments (2)

Just wanted to drop in and say—you absolutely nailed it with this piece. 🎯 Your writing keeps getting better and better, and it's such a joy to read your work. 📚✨ Keep up the amazing work—you’ve got something truly special here. 💥 Super proud of your writing! 💖🙌 Can't wait to see what you create next! #KeepShining 🌟 #WriterOnTheRise 🚀

Good story ♦️⭐️♦️