The Book They Tried to Burn: How Galileo’s Final Work Defied the Inquisition

Galileo Galilei was silenced, censored, and condemned by the Church. But his greatest act of defiance, the secret writing and smuggling of his final book, helped transform the scientific world forever.

The book should not have survived.

In the early months of 1638, under the shroud of secrecy, a manuscript was concealed within a bale of wool, prepared to cross the perilous Alpine passes northward toward Leiden, a sanctuary for intellectual freedom in the Dutch Republic. Its author, Galileo Galilei, blind, frail, and imprisoned by his own Church in Arcetri, near Florence Italy, waited anxiously. It carried not only his life's work but a challenge to those who sought to silence him.

Galileo Galilei, once celebrated across Europe as a towering genius of astronomy, mathematics, and physics, had transformed humanity’s understanding of the cosmos. In earlier days, his telescope had pierced the heavens, revealing moons orbiting Jupiter, mountains on the Moon, and the countless stars of the Milky Way, discoveries that shattered age-old assumptions. Galileo's reputation had soared, gaining him patrons among princes, kings, and cardinals. Yet by 1638, his name was synonymous not just with innovation but with controversy and defiance.

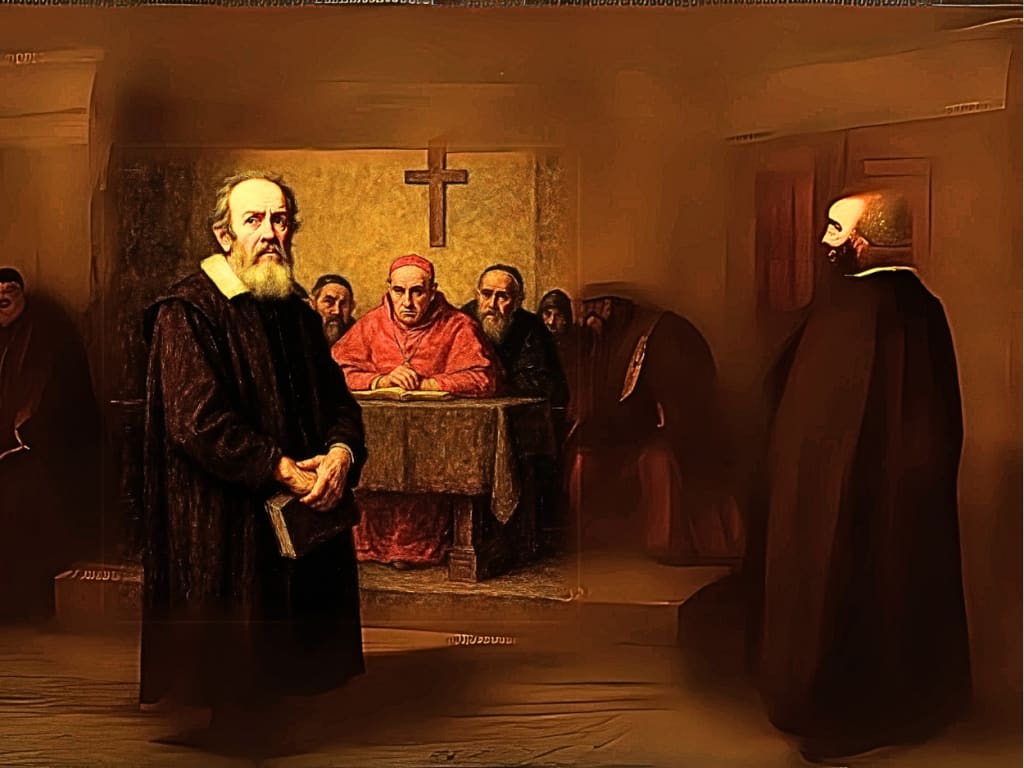

In 1633, Galileo had stood humiliated before the Roman Inquisition, forced to deny the truth he saw written in the stars, i.e.: that the Earth moves around the Sun. At that time, the dominant worldview was grounded in the teachings of the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle and the 2nd-century astronomer Claudius Ptolemy, whose geocentric model had been embraced by the Catholic Church for centuries. According to this view, the Earth stood motionless at the center of the universe, with the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars embedded in crystalline spheres that rotated around it in perfect, unchanging circles.

This geocentric cosmology was not merely a scientific model; it was woven into the theological and philosophical fabric of medieval and Renaissance Europe. The idea of an Earth-centered universe aligned with certain scriptural interpretations that portrayed humanity and by extension, Earth, as the focal point of God's creation. To challenge this cosmic order was to risk challenging the spiritual and social order upheld by the Church.

So, Galileo, threatened with torture and execution, publicly recanted heliocentrism, condemning himself to house arrest for the rest of his life. The Church believed it had finally subdued Galileo, Italy’s greatest scientist. Yet behind the closed doors of his villa, Galileo had not surrendered. Though his eyesight deteriorated and his health waned, Galileo’s mind remained clear, defiant, and insatiable. He had good reason to remain steadfast. Over the preceding decades, Galileo had forged some of the most groundbreaking discoveries in the history of science. With his telescopic observations, he had unveiled a universe far more dynamic and complex than anyone had imagined. In 1610, he discovered four moons orbiting Jupiter, now known as the Galilean moons, providing the first direct evidence that not all celestial bodies revolved around the Earth. But Galileo’s genius extended beyond the heavens. He revolutionized the study of motion, laying the foundation for modern physics. Through careful experimentation, he demonstrated that objects fall at the same rate regardless of their mass, a profound challenge to ancient teachings. He also formulated the law of inertia, a principle later refined by Isaac Newton. His method of systematic observation, experimentation, and mathematical analysis would become the bedrock of the scientific method.

Even in forced isolation, his passion for discovery continued. Quietly, meticulously, he worked on his masterpiece, a new book titled Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Relating to Two New Sciences. This manuscript explored not astronomy, but physics, specifically, the motion of objects, the strength of materials, and foundational concepts in mechanics. If published, it would revolutionize science. But it was also explicitly forbidden.

As Galileo’s pen scratched out truths the Church would not allow, his closest disciples, notably his devoted student Vincenzo Viviani, risked imprisonment themselves, diligently transcribing every word. To Galileo, the manuscript was more than intellectual rebellion; it was redemption, a last defiant whisper against the roar of censorship.

Yet, Galileo knew he could not publish within Italy's borders. The Catholic Church had placed a strict ban on any writings that supported or even hinted at heliocentrism or ideas that contradicted Church doctrine. His earlier book, Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, had already been condemned, and Galileo himself was under constant surveillance. Any new work bearing his name,or even suspected to be his, would be immediately confiscated, and those involved in its production could face severe punishment, including excommunication or imprisonment. The Inquisition’s reach was vast, and Italy’s printers were tightly controlled. Publishing his manuscript openly would have been tantamount to a death sentence for both the book and those associated with it.

He depended on an underground network of allies across Europe, those willing to take risks for the pursuit of truth. These allies arranged for the manuscript's covert transport to the Netherlands, hidden among merchant goods. Its journey was perilous, passing through checkpoints manned by those loyal to the Church, authorities intent on seizing any banned texts.

The manuscript reached Leiden safely, where the esteemed printing house Elzevir immediately recognized its significance. Published swiftly, the book spread across Protestant Europe like wildfire, hailed as a scientific triumph. Galileo’s final act of defiance had succeeded.

But the Church’s response was swift and severe. Discourses was placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, the official list of banned books. Reading or possessing Galileo’s writings became punishable by imprisonment or worse. Copies were hunted, seized, and burned publicly to demonstrate the Church’s resolve against heresy.

Yet, as history would repeatedly show, banning a book only enhanced its power. Galileo’s work survived in secret libraries and hidden collections. Scientists and philosophers throughout Europe, including Isaac Newton, Christiaan Huygens, and René Descartes, absorbed Galileo’s groundbreaking ideas, pushing human knowledge forward despite the threats.

Over the following centuries, the narrative of Galileo’s conflict with the Church was simplified into a stark binary, a symbolic martyrdom in the eternal battle between science and religion. The complexities of his story, the intricacies of court politics, personal rivalries, and ideological struggles were flattened into convenient propaganda for Enlightenment thinkers, seeking examples of church oppression.

Lost within this simplified myth were Galileo’s own nuanced defiance, the quiet heroism of his allies, and the emotional struggle he endured. Forgotten, too, were the personal bonds that sustained him. Maria Celeste, Galileo’s daughter, a nun whose constant letters offered emotional strength and intellectual companionship, vanished from the historical record for centuries. Yet, without her steadfast support, Galileo might never have completed Discourses.

Maria Celeste’s letters reveal a side of Galileo obscured by history: the weary father, the gentle mentor, the grieving and sometimes lonely figure whose strength of spirit matched his brilliance of mind. Her voice, nearly erased, restores the human dimension to Galileo’s resistance. Together, their correspondence portrays a powerful story of love, resilience, and intellectual courage.

Galileo spent his last days at Arcetri, blind, frail, and nearly forgotten by society, yet deeply satisfied knowing that his life's work, his defiance, would endure. He died quietly on January 8, 1642, unaware that his banned book had ignited a scientific revolution across Europe.

Only centuries later, fully rediscovered and rehabilitated, would Galileo’s Discourses be universally recognized as foundational to modern science. Yet even today, few appreciate the danger and heroism involved in its creation and dissemination. Galileo’s defiance, the intricate network of resistance, and the courage of those who smuggled his manuscript out of Italy remain rarely acknowledged, still overshadowed by simplified myths and the enduring image of Galileo as a solitary martyr.

The true story is richer and far more powerful than the simplified narratives often taught in textbooks. It is a tale of quiet heroism and collective defiance, of courage that extends beyond Galileo himself, encompassing students, printers, allies,and a devoted daughter, who risked their own freedoms so that the truth might live.

Today, when we open Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Relating to Two New Sciences, we hold not just pages of scientific brilliance but the very spirit of intellectual freedom. We read the words Galileo penned in darkness, blind but never silenced, defiant even in isolation.

These are the pages history tried to erase, the book they attempted to burn. But the flames of censorship failed; the ideas survived. Galileo’s true legacy is not simply the knowledge he uncovered but the courage he demonstrated, reminding future generations that no power can permanently silence the truth.

Galileo’s greatest victory was that despite all attempts to silence him, the page they tried hardest to burn is precisely the one we still read today.

About the Creator

Strategy Hub

Pharmacist with a Master’s in Science and a second Master’s in Art History, blending scientific insight with creative strategy to craft informative stories across health science, business history and cultural enrichment. Subscribe & follow!

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.