Swat Under Water"

Documenting One of Pakistan’s Worst Natural Disasters

The rain began quietly, as it always did in the monsoon season, with a light drizzle brushing the pine-covered slopes of the Swat Valley. Children ran through the narrow streets of Bahrain, laughing, barefoot in the mud, as their mothers called them inside. Few paid attention to the gathering clouds—after all, rain in Swat was nothing new.

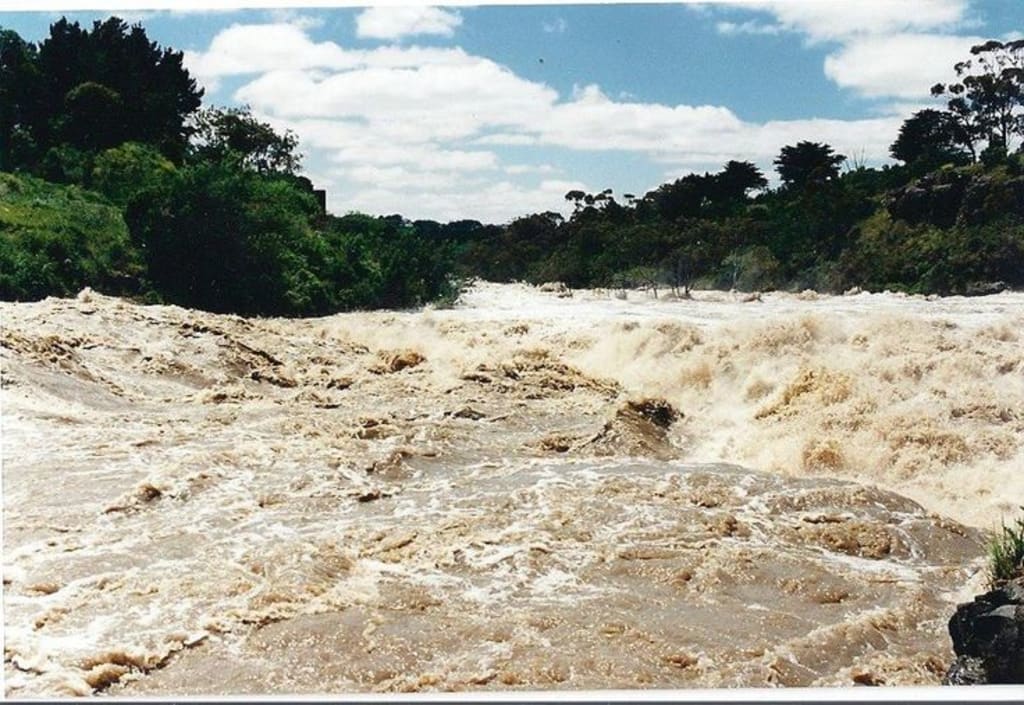

But by nightfall, the drizzle had become a downpour. The Swat River, normally a source of life and beauty, began to churn violently. Locals along the riverbank noticed the rising water with growing concern. Warnings were whispered among neighbors, but for many, it felt like another rainy night in the mountains.

By dawn, it was clear this was no ordinary flood.

Bridges—centuries old, crafted from wood and stone—were swallowed by the surge. Houses built too close to the river collapsed into the waters like sandcastles. Markets, schools, and clinics disappeared under torrents of muddy water. Families rushed to higher ground, clutching children, elders, and whatever belongings they could carry.

In the village of Madyan, 16-year-old Zareen stood helplessly beside her mother as they watched their home crumble. It was a small house, but it was theirs—built by her father, a mason who had passed away just three years earlier. All of Zareen’s schoolbooks, her father’s tools, her mother’s sewing machine—they vanished into the roaring brown river in seconds.

“The sound was like thunder and crying at once,” she would later tell a journalist. “It was as if the earth itself was in pain.”

The Swat River, once a symbol of peace, had become a nightmare.

A Valley in Crisis

The 2022 floods were among the worst in the history of the valley. Roads linking major towns like Mingora, Kalam, and Bahrain were cut off. Entire communities were stranded, with no food, no electricity, and no medical supplies. Helicopters buzzed overhead, attempting to deliver aid, but landslides and continued rainfall made many areas unreachable.

For days, Zareen and her mother lived on a hillside with other displaced families, surviving on dry bread and bottled water provided by volunteers. She watched as her younger cousins cried from hunger, and elders huddled under plastic sheets in the cold mountain rain.

What was once a lush valley full of orchards and tourists had turned into a landscape of devastation.

“The Swat I knew,” said Rehman Shah, a retired schoolteacher from Kalam, “has been washed away. The river has taken not just homes, but memories, dreams, and the work of generations.”

Beyond the Waters: The Human Cost

The numbers told part of the story—hundreds dead, thousands displaced, millions of rupees in losses—but they could not capture the heartbreak. Farmers lost their fields, shopkeepers their stalls, students their schools. Many had no insurance, no savings, and no idea how to begin again.

Rescue efforts, led by local volunteers, the army, and international NGOs, helped bring immediate relief, but the trauma lingered. Mental health professionals later reported a sharp rise in anxiety and depression among children and adolescents in the valley.

And yet, amid the destruction, there were flickers of resilience.

A group of university students from Swat organized crowdfunding campaigns, delivering food and blankets to villages no aid had reached. Teachers conducted makeshift classes under trees. Local carpenters began rebuilding bridges with whatever materials they could find. The community, though battered, refused to surrender.

Lessons in the Water

Experts blamed deforestation, poor urban planning, and unchecked construction along the river for the scale of the disaster. Once covered in thick forests, the Swat hills had been stripped bare over decades. Without roots to hold the soil, landslides became more frequent. The river’s natural path was narrowed by buildings and roads, giving the water nowhere to go but straight through homes and markets.

“This was not just a natural disaster,” environmentalist Farzana Khattak told a local news channel. “It was a man-made tragedy, years in the making.”

The government vowed to rebuild smarter—with better drainage, flood defenses, and stricter zoning laws. But locals remained skeptical.

“We’ve heard promises before,” said Zareen’s uncle, who now lived in a tent provided by the Red Crescent. “But when the next rains come, will we be safer? Or just more afraid?”

The River Remembers

Today, nearly three years later, the Swat River flows calmly again, its surface glinting beneath the sun like a sheet of glass. Tourists have slowly returned to Kalam and Malam Jabba. Fruit trees are blooming once more, and children play cricket in fields that were once underwater.

Zareen is back in school, studying to become a civil engineer. She dreams of building flood-resistant homes, ones that can withstand the river's fury.

“I used to fear the river,” she says. “But now I understand it. It gives life—but it demands respect.”

The Swat River remembers, and so does the valley. In every rebuilt house, every new sapling planted, and every prayer whispered at night, echoes of the flood remain—reminders of loss, strength, and the will to begin again.

About the Creator

Hasnain khan

"Exploring the world through words. Join me as I unravel fascinating stories, share insightful perspectives, and dive into the depths of curiosity."

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.