Mentuhotep II: The Pharaoh Who Reunified Egypt, Founded the Middle Kingdom, and Built the Iconic Mortuary Temple at Deir el-Bahri

Mentuhotep II: The Pharaoh Who Reunified Egypt, Founded the Middle Kingdom, and Built the Iconic Mortuary Temple at Deir el-Bahri

Introduction

Mentuhotep II (also known as Nebhepetre Mentuhotep) was one of the most pivotal figures in ancient Egyptian history. Ruling during the 11th Dynasty (circa 2055–2004 BCE), he achieved the monumental task of reunifying Egypt after the chaos of the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BCE). His victories ended a century of fragmentation, marking the beginning of the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BCE), often regarded as a golden age of stability, cultural revival, and artistic innovation. Additionally, Mentuhotep II constructed a groundbreaking mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri on the west bank of Thebes (modern Luxor), which served as a model for later New Kingdom pharaohs, including Hatshepsut. This article explores his life, achievements, and enduring legacy, drawing on archaeological evidence and scholarly analyses.

Historical Context: The First Intermediate Period

The First Intermediate Period was a time of political disarray following the collapse of the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BCE). Central authority crumbled, leading to rival dynasties: the 9th and 10th Dynasties based in Herakleopolis (Lower Egypt) controlled the north, while the 11th Dynasty in Thebes (Upper Egypt) dominated the south. Nomarchs (regional governors) wielded significant power, and civil war, famine, and invasions plagued the land. Egypt, once unified under strong pharaohs like those of the Pyramid Age, splintered into feuding factions.

Mentuhotep II inherited this divided kingdom from his father, Intef III, and predecessors like Intef I and II, who had expanded Theban influence through military campaigns against northern rivals and local nomarchs. As noted in the Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, "Thebes gradually asserted its dominance over Upper Egypt, setting the stage for full reunification under Mentuhotep II" (Shaw, 2000, p. 136).

Reunification of Egypt

Ascending the throne around 2055 BCE, Mentuhotep II launched aggressive campaigns to subdue remaining opponents. Early in his reign (years 1–14), he consolidated control over Upper Egypt by defeating loyalists to Herakleopolis and absorbing nomadic groups. A key turning point came around year 39 of his rule, when his forces captured Herakleopolis, the northern capital, effectively ending the rival dynasty.

Inscriptions from his mortuary temple and tombs of officials, such as the steward Henenu, detail expeditions to quarries and punitive campaigns against Asiatic Bedouins and Libyan tribes. By quelling internal rebellions—evidenced by the destruction of Thinite nomarch tombs at el-Tarif—Mentuhotep II centralized power. He adopted grandiose titles like "Horus of the Two Lands" and "He Who Unites the Two Lands," symbolizing unity.

Archaeologist Dorothea Arnold describes this as "the first true reunification since the Old Kingdom," achieved through a blend of military prowess and administrative reform (Arnold, 1991, p. 45). The result was the Middle Kingdom's foundation: a stable bureaucracy, revived trade (e.g., expeditions to Punt and Byblos), and economic prosperity that lasted over 400 years.

Founding the Middle Kingdom

Mentuhotep II's reunification ushered in the Middle Kingdom, characterized by stronger central government, literary flourishing (e.g., works like the Tale of Sinuhe), and monumental architecture. He moved the capital to Thebes (later shifted to Itjtawy under Amenemhat I of the 12th Dynasty), promoting Theban gods like Amun to national prominence.

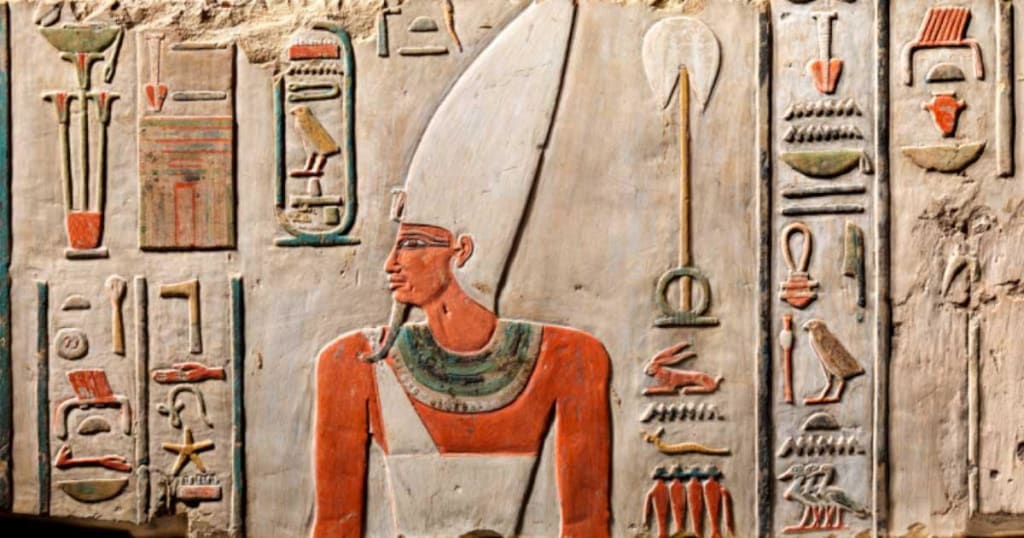

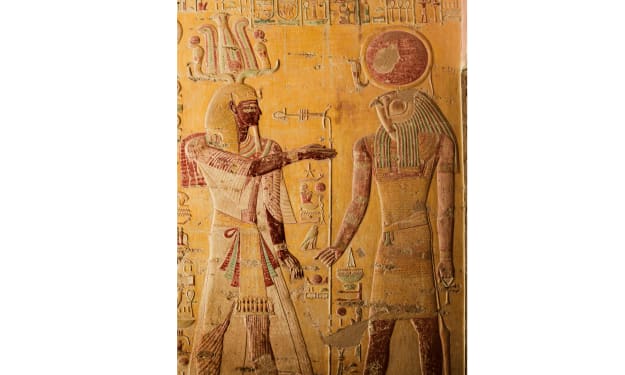

His 51-year reign (per the Turin King List) allowed for reforms that strengthened pharaonic authority. Provincial governors were replaced with loyal appointees, reducing feudalism. Art and propaganda emphasized divine kingship; reliefs depict him smiting enemies in traditional Old Kingdom style but with Middle Kingdom realism.

As Egyptologist Nicolas Grimal observes, "Mentuhotep II not only ended the Intermediate Period but laid the ideological and administrative foundations for the Middle Kingdom's classical phase" (Grimal, 1988, p. 158).

The Mortuary Temple at Deir el-Bahri

Mentuhotep II's most enduring architectural legacy is his mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri, a terraced complex nestled against cliffs opposite Thebes. Built in phases over his reign, it integrated tomb, temple, and cult center—innovative for its time.

The structure features:

A forecourt with sycamore and tamarisk trees (evidenced by plant remains).

Ramp-led terraces rising to a colonnaded upper level.

A central pyramid or mastaba-like core (possibly symbolic).

Reliefs showing battles, hunts, and offerings to gods like Amun and Montu.

Excavations by the Egyptian Expedition of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1911–1931) under Herbert Winlock uncovered statues of the king in Osirid form, sandstone reliefs, and the sarcophagus of queens in a baboon-guarded shaft tomb. The temple's design influenced Hatshepsut's nearby temple (18th Dynasty), which mirrored its terraces.

Dieter Arnold's detailed study highlights its role as a "prototype for New Kingdom Theban temples," blending funerary and divine worship (Arnold, 1979, pp. 12–25).

Legacy and Conclusion

Mentuhotep II died around 2004 BCE and was succeeded by Mentuhotep III, continuing the dynasty until the 12th. His reunification ended over a century of division, birthed the Middle Kingdom's prosperity, and left an architectural marvel at Deir el-Bahri that inspires awe today.

Though less famous than Ramses II or Tutankhamun, Mentuhotep II's achievements reshaped Egypt. As Ian Shaw summarizes, he was "the architect of Egypt's second great era" (Shaw, 2000, p. 149). His temple, a UNESCO World Heritage site, stands as a testament to his vision.

References

Arnold, Dieter. The Temple of Mentuhotep at Deir el-Bahari. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979.

Arnold, Dorothea. "The Destruction of the Tombs of the Thinite Nomarchs." Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, vol. 77, 1991, pp. 45–56.

Grimal, Nicolas. A History of Ancient Egypt. Blackwell, 1988.

Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press, 2000.

Winlock, Herbert E. Excavations at Deir el Bahri: 1911–1931. Macmillan, 1942.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.