The History of Egyptian Hieroglyphs

The History of Egyptian Hieroglyphs

Egyptian hieroglyphs, often referred to as "sacred carvings" from the Greek term *hieroglyphikos*, represent one of the world's oldest writing systems. These pictorial symbols, known to the ancient Egyptians as *mdw.w-nṯr* or "words of the gods," combined logographic, phonetic, and determinative elements to convey language. Emerging around 3200 BCE during the Naqada III period, hieroglyphs evolved from proto-literate symbols used in the Early Bronze Age, marking a pivotal advancement in human communication.

## Origins and Early Development

The roots of hieroglyphs trace back to prehistoric rock art created by hunting communities west of the Nile River, with motifs appearing on Gerzean pottery as early as 4000 BCE. The earliest confirmed examples date to around 3200-3100 BCE, found on clay labels and tokens in tombs like U-j at Abydos, used for administrative purposes such as labeling goods, recording numbers, and noting origins. These proto-hieroglyphs likely developed independently in Egypt, though some scholars suggest possible influences from Sumerian cuneiform due to cultural contacts. By the late Predynastic period, just before 2925 BCE, the system had matured into a full writing form with phonetic values, distinct from mere pictorial representations.

The first complete sentence in hieroglyphs appears on a seal impression from the tomb of Seth-Peribsen in the Second Dynasty (c. 28th-27th century BCE). During the Old Kingdom (c. 2686-2181 BCE), the script standardized with about 800 signs, used primarily for monumental inscriptions on stone, tombs, and royal artifacts like the Narmer Palette (c. 3100 BCE). Hieroglyphs were inscribed in rows or columns, read from right to left or vice versa, with the direction indicated by the facing of asymmetrical figures like birds or people.

## Evolution and Use in Ancient Egypt

By the Middle Kingdom (c. 2050-1710 BCE), hieroglyphs had refined to around 750-900 signs, incorporating uniliteral (single consonant), biliteral, and triliteral phonograms, alongside logograms and determinatives that clarified meaning without being pronounced. Vowels were typically omitted, making it an abjad script. The system was versatile, appearing on diverse materials including papyrus (from the First Dynasty), wood, metal, ceramic, bone, leather, and ostraca (pottery shards).

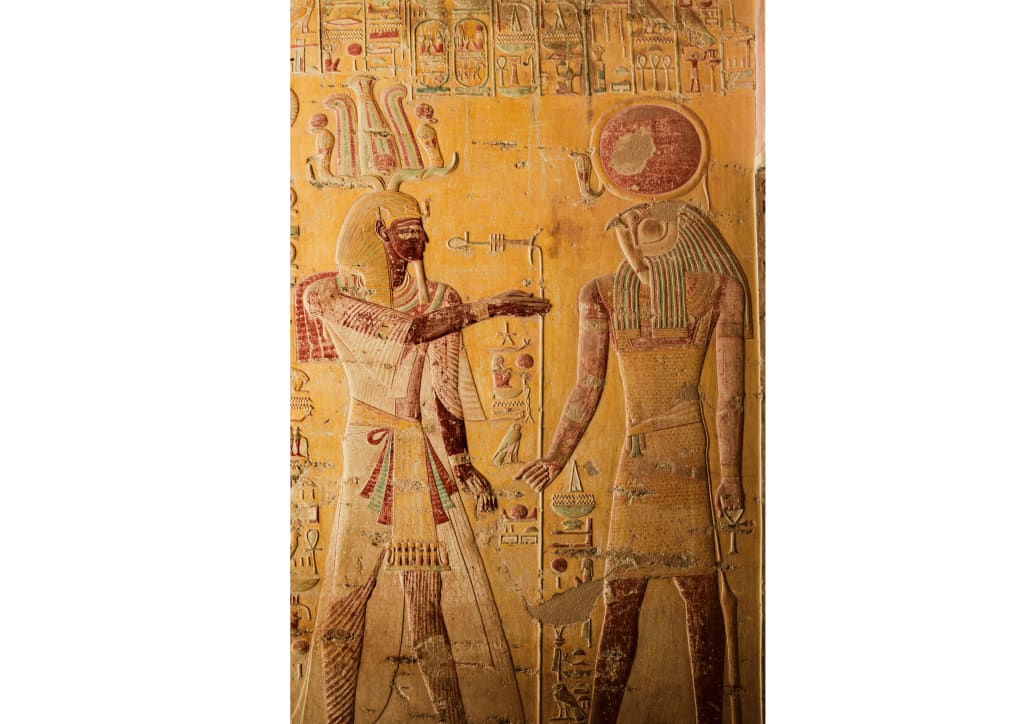

In the New Kingdom (c. 1550-1070 BCE), hieroglyphs flourished in religious texts like the Pyramid Texts (c. 2500 BCE) and Coffin Texts (c. 2000 BCE), as well as in temples and tombs for record-keeping, royal decrees, and dedications to deities. According to Egyptian mythology, the god Thoth invented writing to aid wisdom and memory, granting it to scribes who held high societal status. The script's pictorial nature made it ideal for monumental display, coexisting with cursive variants for everyday use.

## Derived Scripts: Hieratic and Demotic

Hieroglyphs spawned more practical scripts. Hieratic, a stylized cursive form, developed alongside hieroglyphs for religious, commercial, and administrative writing on papyrus and ostraca, written right to left. By the 7th century BCE, demotic ("writing for documents") emerged as an even more abbreviated version, replacing hieratic for most non-religious purposes while hieroglyphs remained for formal inscriptions. During the Ptolemaic (332-30 BCE) and Roman periods (30 BCE-395 CE), the number of signs ballooned to over 5,000, incorporating Greek influences.

## Decline and Loss of Knowledge

Hieroglyphs persisted for nearly 3,000 years but declined with foreign conquests. After Alexander the Great's invasion in 332 BCE, Greek became dominant, and by AD 100, an alphabetic Coptic script evolved from demotic and Greek, replacing older forms as Christianity spread. The last known hieroglyphic inscription, a graffito at Philae temple, dates to AD 394. By the 5th century CE, knowledge of the script was lost following the closure of pagan temples. Medieval Arab scholars and European Renaissance humanists viewed hieroglyphs as symbolic rather than phonetic, with attempts by figures like Dhul-Nun al-Misri (9th century) and Athanasius Kircher (17th century) yielding limited success.

## Decipherment

The breakthrough came with the discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799 during Napoleon's Egyptian campaign. This artifact, a decree from 196 BCE honoring Ptolemy V, featured parallel texts in hieroglyphs, demotic, and Greek. Scholars like Silvestre de Sacy, Johan David Åkerblad, and Thomas Young identified phonetic elements in royal names. Jean-François Champollion achieved full decipherment in 1822, recognizing the script's mix of figurative, symbolic, and phonetic components, as announced in his *Lettre à M. Dacier*. His 1836 *Egyptian Grammar*, published posthumously, provided the foundation for modern Egyptology.

## Legacy and Significance

Hieroglyphs unlocked the secrets of ancient Egypt, revealing a civilization predating classical Greece and Rome. As an ancestor to the Phoenician alphabet, they influenced most modern scripts. Today, with a corpus of 5-10 million words, they continue to inform history, linguistics, and culture, standing as a testament to human ingenuity in recording thought.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.