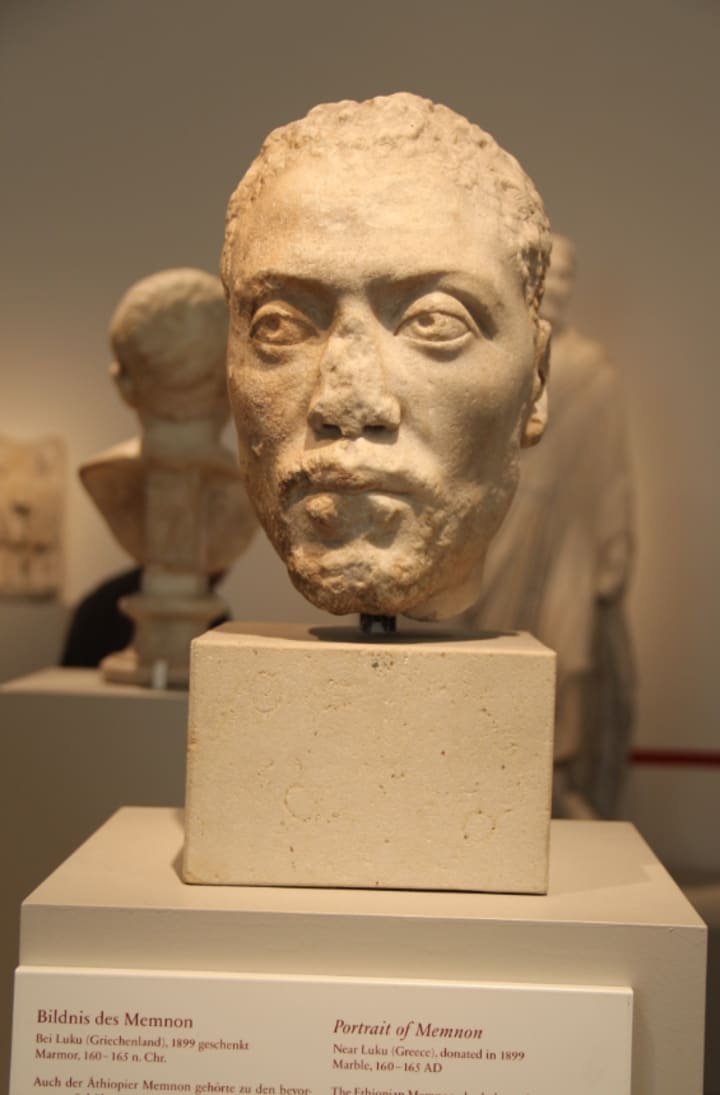

Memnon, King of Aethiopa

An Exploration of a Black King in Greco-Roman Mythology

Memnon is not exactly the most well-known or consequential figure in the extensive corpus literature surrounding the Trojan War – Homer doesn’t even give him any lines. Yet the Aethiopian king’s parentage and later characterization offer hints as to how the Ancient Greeks and later Romans might have viewed their Nubian neighbors.

Greek Attestations

(8th Century BC) Homer’s Odyssey mentions Memnon exactly once, only to say that he is the most handsome man Odysseus has ever known.

(8th Century BC) The Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite tells us that the Eos – Titaness of the Dawn – took the Trojan prince Tithonus as her lover, while Hesiod’s Theogany clarifies that they had a son: Memnon, King of the Aethiopians.

(6th Century BC) The Aithiopis, a mostly-lost epic attributed to a pupil of Homer. The fragment we do have tells us that Memnon defeated Antilochus – a friend of Achilles – only to be defeated by Achilles in turn. Eos pleads with Zeus to grant Memnon immortality, which he does.

Roman Attestations

(1st Century BC) Virgil’s Aeneid mentions Memnon in passing as being ‘swarthy’ and possessing an ‘Indian’ crew.

(3rd Century AD) Quintus of Smyrna’s Posthomerica, written with access to the full text of the Aithiopis, gives us the most detailed account of Memnon’s participation in the Trojan War. He is described as a giant warrior-king leading a host of ‘swarthy Aethiops’ who are later also characterized as having been ‘burned with fire’. Quintus tells us that Memnon slew the heroes Pheron and Antilochus and cut a bloody swath through his enemies until, at last, he comes face-to-face with Achilles.

After wounding Achilles, Memnon boasts of his superior divine lineage. He argues that, as the son of a Titaness who was nursed by the Hesperides, he outranks Achilles, who he names the son of a mere Nereid – an oceanic nymph. Achilles shoots back that he can trace his descent straight up to Zeus (through his grandfather, Aeacus, son of Zeus and the nymph Aegina) and that his mother’s deeds place her high in the esteem of Olympus. He then remarks on the silliness of this argument and demands that they return to stabbing one another.

Quintus takes considerable care to inform us that Achilles and Memnon are evenly matched – both in their physical prowess, and in the esteem with which the gods hold them. Zeus empowers both combatants to fight beyond the capabilities of mortal warriors, and even the Fates seem undecided as to who should win. In the end, Eris – goddess of discord – casts the deciding vote in Achilles’ favor, and Memnon is slain.

In the wake of Memnon’s death, Eos is then described as bringing darkness to the world in her grief. The Titaness of the Dawn fully intends to never again bring the dawn, and declares in a fit of spiteful sarcasm that Zeus can have Thetis bring light to the world, since her son was clearly more worthy of life than hers. This tantrum ends the moment Zeus appears and demands that Eos continue to do her job.

The last relevant detail worth noting in the Posthomerica is that it attributes the death of Achilles to Apollo – specifically, Phoebus (Bright) Apollo – and that it has Achilles die almost immediately after Memnon.

Aethiopia: Nubia not Ethiopia

Aethiopia, Aethiopian, and Aethiops were Greek exonyms. An exonym is a name assigned to a people or nation by foreigners – contrasted with an endonym, which is the name the people use to describe themselves. For an ironic example: Greece is actually a Roman exonym used to describe Hellas, the endonym for the same region and culture and the root of such terms as Hellenism, Pan-Hellenic, and Hellenistic.

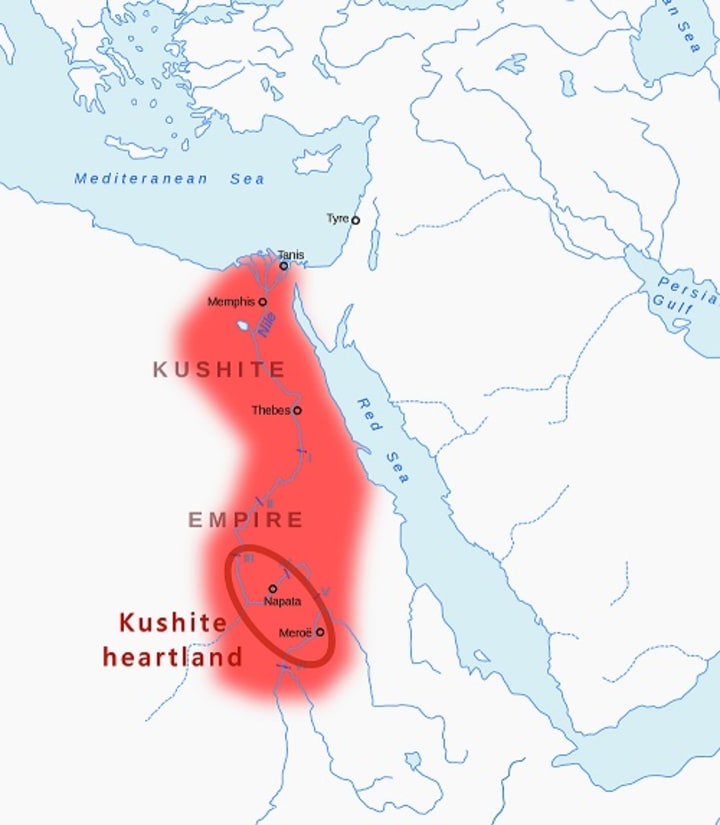

The Greek word Aithiopia literally translates to mean ‘burnt-face’, and seems to have begun as a general term used to describe people who the Greeks considered to be dark-skinned. However, by the time Herodotus was writing his Histories around 440 BC, he felt comfortable defining Aethiopia as those lands south of Egypt along the Nile. By naming Meroë the capital of all Aethiopia (which he does in Book 2, Chapter 29, Section 6), Herodotus further narrows down the definition of Aethiopia to be synonymous with the Nubian Kingdom of Kush.

While Herodotus was writing 3-4 centuries after the earliest attestations of Memnon, circumstantial evidence suggests that Homer, the author of the Aithiopis, and Hesiod likely also conceived of Memnon as a Nubian king.

First, let’s talk about timing. While the Trojan War was framed as having taken place during the Mycenaean Age (1750 – 1050 BC), Hesiod and Homer both composed their works sometime between 800 and 701 BC. The Hellenistic world of Hesiod and Homer’s era was well-connected with the lands of Egypt by trade, even if the first permanent Greek settlement in Egypt wouldn’t arise until the mid-600s BC.

Why is this relevant? Because the 25th Dynasty of Egypt – also known as the Kushite Dynasty – united Nubia and Egypt into a single polity from 746 to 643 BC.

Right around the time Homer and Hesiod were writing, the Kushites were emerging as a significant regional power. While Homer might not have attached any importance to Memnon or his homeland – as evidenced by the complete lack of elaboration as to his family line by an author who LOVED detailing the family histories of his characters – Hesiod clearly felt otherwise. The Aethiopians were important enough in Hesiod’s eyes – quite possibly due to the recent conquest of Egypt by the Nubians – that the divine lineage of their kings merited an explanation in his Theogany.

Memnon’s Family Tree

Actually, let’s talk about Memnon’s parentage for a moment. Memnon’s father is the Trojan prince, Tithonus, and his mother is Eos, Titaness of the Dawn. Let that sink in for a moment. The son of a Trojan prince – Troy was located in present-day Hisarlık, Turkey – and a Greek Titaness is the King of Aethiopia.

By the standard traditions of Greek patrimony this makes no sense, so why did Hesiod construct Memnon’s family tree this way? If we’re assuming that Memnon’s family tree is the result of deliberate decision-making on Hesiod’s part – and I’d like to think we can extend him that courtesy – then two possible answers present themselves:

A) The Trojan and Aethiopian royal families intermarried so often that being a Trojan royal might have reasonably given Memnon a claim to the Aethiopian throne (think King Edward III of England claiming the French throne at the outset of the Hundred Years War).

B) Eos was the Greek exonym for an Aethiopian goddess, whose blood conferred upon Memnon the divine right to rule.

While Perseus and Andromeda do present us with an example of a Greek prince marrying Aethiopian royalty – more on them another time – my personal conspiracy theory is that Eos was used by Hesiod as a figurative stand-in for Nubian divinity in general, and possibly Isis in particular.

You see, the exact rules of succession adhered to by the Kingdom of Kush are the subject of lively academic debate. One theory, however, is that the Kushites followed a matrilineal line of succession. Under these rules, if Kush was ruled by a qore (king) then the throne passed to the child of his oldest sister upon his death, not to his own children. If the heir happened to be a woman, then she inherited the throne as kandake (queen, and the root of the name Candace) in her own right. If the kandake’s first child was a son, then we repeat the process at step one. While this is hard to prove conclusively, the Kingdom of Kush did have an unusually high number of women ruling in their own name throughout its history.

If we place Memnon into the context of a matrilineal line of succession for the Kushite throne, suddenly his kingship becomes a lot more plausible. If a Trojan prince like Tithonus married the eldest sister of the Kushite qore, then his son would inherit the throne. Now, even if this arrangement made sense to the Nubians, it might have seemed bizarre to Hesiod’s Greek audience. To smooth over this cultural disconnect, we get Eos in the place of a mortal Kushite princess.

Eos: Rose-Fingered Kidnapper

While abducting mortal lovers was an unfortunately common pass-time for the male Olympians, the same cannot be said of their female counterparts – Eos and Aphrodite are the only two exceptions to this rule that I’m aware of. That Eos shares this unusual penchant for predation with a foreign goddess – a wealth of scholarship has identified Aphrodite’s origins as the Mesopotamian goddess, Ishtar – reinforces the notion that the Greeks deemed this behavior aberrant.

The Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite relays the story of Eos abducting Tithonus, which suggests that Eos’ aberrant predatory behavior was nevertheless an established part of her characterization at the time Hesiod was writing his Theogany. Eos might therefore have presented Hesiod with a convenient means of explaining Memnon’s status as King of the Aethiopians in terms his audience would understand.

It’s actually not hard to imagine his thought process:

‘Memnon was fighting at Troy. Why?’

‘Because his father is a Trojan prince.’

‘Then how is he King of Aethiopia?’

‘I hear they’re ruled by their mothers and wives over there. Memnon was king because of his mother’s status.’

‘What self-respecting Greek prince would marry into a family where HIS bloodline was less important? Where women are in charge?’

‘If women are in charge, then they probably abducted him – the way a man would here.’

‘But Memnon was a hero – how could a hero spring from the loins of a man who was abducted by women?”

‘Men get abducted by gods all the time…’

‘Hey, Eos abducted a Trojan prince that one time. She’s associated with the sun, and the Aethiopians worship sun gods, right? Let’s make Tithonus Memnon’s father!’

Establishing Eos and Tithonus as Memnon’s parents not only might have provided Hesiod’s audience with a religious explanation for the strange ways of Egypt’s new rulers, but it also imparts a certain legitimacy to the foreign Aethiopians by explicitly including them in the wider Greek world via both Trojan and divine blood.

Why Eos and not Aphrodite?

Some might point to Virgil’s description of Memnon’s crew as ‘Indians’, the initial vagueness of the term ‘Aethiopian’, and the assertion of his contemporary, Diodorus Siculus, that Tithonus founded the city of Susa as evidence of a Mesopotamian or Far-Eastern Memnon. Firstly, Susa could simply have been the place Tithonus was abducted from. Secondly, I’d like to pose a simple question: If Hesiod intended to imply an Eastern lineage for Memnon, why not have Aphrodite serve as his mother instead of Eos?

Aphrodite also abducts mortal men to serve as her lovers, Aphrodite has a deeper connection to the Trojan war – arguably being one of the main causes for the conflict – and we’ve already touched on her established descent from Ishtar. If Hesiod’s intent was to paint Memnon as a semi-divine king of the East, it would have made a lot of sense to make his mother Aphrodite. But, he didn’t.

Now, there are a lot of similarities between Aphrodite and Eos, but where Eos diverges most sharply from Aphrodite is in her connection to the heavens. Aphrodite inherits from Ishtar an association with the Morning Star (later identified as the planet Venus). Eos is not only responsible for bringing the dawn itself, she is married to the Titan Astraeus (literally ‘of the stars’), and through this marriage she gives birth to the Morning Star. Interestingly, Eos is also the mother of the four ‘winds’ – Zephyrus, Boreas, Notus, and Eurus – and thus, something of a sky goddess.

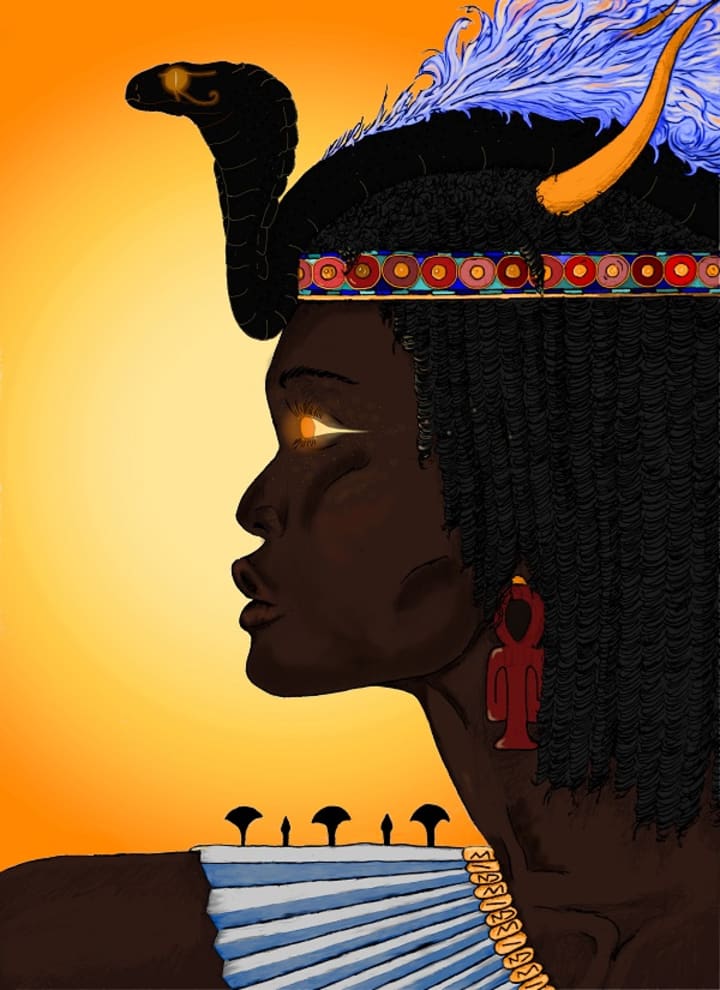

Let’s put a pin in Eos and talk about Isis.

During the time that Hesiod was writing, Isis and her husband, Osiris, were the most widely worshipped deities in Egypt and Nubia. Isis played a vital role in the protection of kings, kingship, and the kingdom – represented in myth via her protection of Osiris and Horus, the pharaohs of the dead and living respectively. By the time of Memnon’s earliest attestations, Isis also had a long-standing association with the sun and stars.

The Pyramid Texts (dating back to the 2nd Millennium BC) associate Isis, Osiris, and Horus with Sopdet, Sah, and Sopdu (the gods of Sirius, the constellation Orion, and the sky), and this association later became full-on syncretism as Isis-Sopdet, Osiris-Sah, and Horus-Sopdu. Meanwhile, stories where Isis tricks the aging sun-god Ra into giving up some of his power predate Hesiod by around 2 centuries, as does the inclusion of the sun disk as part of her divine panoply. When the later Greek dynasties of Egypt gave Isis explicit dominion over the sky, it was a reinforcement of her existing associations rather than a novel innovation.

It is also worth mentioning at this point that the Greeks developed a habit of writing that other people simply worshipped the Olympians by different names and with different forms. This becomes very explicit by the time of Herodotus, who simply states that the Nubians worship Zeus and Dionysus rather than using the localized names of Amun and Osiris, but even Homer observes that Poseidon was hanging out in Aethiopia at one point during the Trojan War.

If you were Hesiod and you wanted to place Memnon’s status as King of the Aethiopians in the religious and political context of the Kushite Dynasty of Egypt, it makes more sense to write Eos as his mother because she maps more closely to Isis. Memnon’s mother being Isis-as-Eos also further contextualizes his boastful exchange with Achilles – to his own people, being the son of Isis would be a much bigger flex than being the grandson of Hyperion or the great-grandson of Uranus.

So if there are plenty of hints and context clues suggesting that Hesiod imagined a Nubian Memnon, and if later Greek, Roman, and even Assyrian writers further clarified that they considered Aethiopia to be Nubia, why the swerve with Virgil?

Virgil, Quintus, and the Meroitic War

The composition of Virgil’s Aeneid (29-19 BC) aligns rather closely with the three-year war fought between the burgeoning Roman Empire and the Kingdom of Kush. Fresh on the heels of annexing Egypt, the Roman Empire first thought to expand southward into Nubia (remember, Kush had lost control of Egypt proper from 643 BC onward), but they were checked by the armies of the famously one-eyed Kushite Kandake, Amanirenas. Augustus subsequently signed a treaty with Amanirenas fixing the southern border of the Roman Empire – a treaty that would stand for another 300 years.

Virgil was commissioned to write the Aeneid by Augustus, in order to glorify his mythical Trojan ancestor, Aeneas. We should also note that Aeneas is written as the son of a Trojan prince and the goddess Aphrodite (Venus to the Romans). Virgil might therefore have felt that glorifying the ancestor of Amanirenas – an ancestor with a nearly identical divine pedigree, no less – in the immediate aftermath of the war was a risky proposition. He may also have been aware that Nubia was a vital part of the Red Sea trade routes connecting Egypt (now Rome) with India.

Thus, Virgil diminishes Memnon’s role in the Trojan War – something he may have felt justified in doing given Homer’s similarly negligible treatment of the character – and implies that Memnon was Indian rather than Nubian. After all, Virgil says that Memnon is surrounded by Indians, without stating that Memnon himself is Indian. I like to imagine that he did this to avoid unnecessary criticism from contemporary readers who were familiar with the previously discussed religious epics, and Herodotus’ works.

Now, let’s talk about a much later Roman poet: Quintus of Smyrna. As we don’t have the full Aithiopis, we don’t know how much of the Posthomerica was a faithful translation of the original versus Quintus’ contributions, but both possibilities provide their own insight. If what we read in the Posthomerica is ripped straight from the source, then we can infer that the Ancient Greeks saw Kush – or Kushite Egypt specifically – as their equals in terms of raw might and divine favor. However, if most of what Quintus wrote about Memnon was his own invention, then it suggests that he wanted to justify Rome’s past defeat at the hands of Kush by painting Memnon – a representation of Nubia’s past – as a worthy and divinely favored warrior.

As Quintus was writing either during, or in the immediate aftermath of the Crisis of the Third Century, it’s also possible that his praiseful depiction of Memnon was a subtle show of support for the Palmyrene Empire – a short-lived state stretching from Anatolia to Egypt that briefly broke away from the Roman Empire during the aforementioned Crisis. Not only did the Palmyrene Empire lay claim to Memnon’s former kingdom and the homeland of his father, but it was founded by a woman: Queen Zenobia.

History’s Footprints in Fiction

Now, it’s impossible to know for certain what was going through the heads of these ancient poets, but contemporary events have a well-documented tendency to influence even works of myth, spirituality or fiction. The Prose Edda is undoubtedly influenced by the political goals of its composer, Snorri Sturlson, who wished to provide a religious and cultural justification for his efforts to unite Iceland and Norway. Confucius wrote about the importance of good governance, ritual, and family structure at a time of wide-spread civil war – almost certainly because those virtues were under constant threat. J.R.R. Tolkien served in World War I, and much has been written about how the Great War shaped the narrative of the Lord of the Rings.

So when I encounter a mythical figure like Memnon, I see them as fascinating windows into the contemporary events or beliefs that might have shaped their fluctuating characterization.

There’s also something unexpectedly wholesome about Achilles and Memnon pausing their fight-to-the-death to brag about their moms.

About the Creator

T. A. Bres

A writer and aspiring author hoping to build an audience by filling this page with short stories, video game reviews/rants, history infodumps, and comparative mythology conspiracy theories.

Come find me @tabrescia.bsky.social

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.