As a leading contender for the title of ‘Humanity’s Birthplace’, it should come as no surprise that Ethiopia has a long, rich history. Sadly, this history is seldom studied by Western scholars and is barely acknowledged by our pop culture. This is a shame, because I would trade countless biopics and period pieces centered on Napoleon, Henry VIII, Elizabeth I, and Eleanor of Aquitaine for one well-researched portrayal of the life and times of Empress Mentewab – one of the most interesting women in Ethiopian history.

Her Names

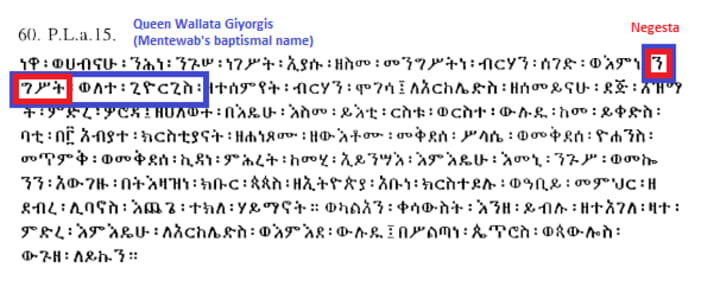

Mentewab went by three names during her lifetime. Mentewab (lit. how beautiful) was the most commonly used, and seems to have been her birth name. Walatta Giyorgis (lit. daughter of St. George) was her baptismal name, which she used on some formal documents, while her regnal name was Berhan Mogassa (lit. Glorifier of Light).

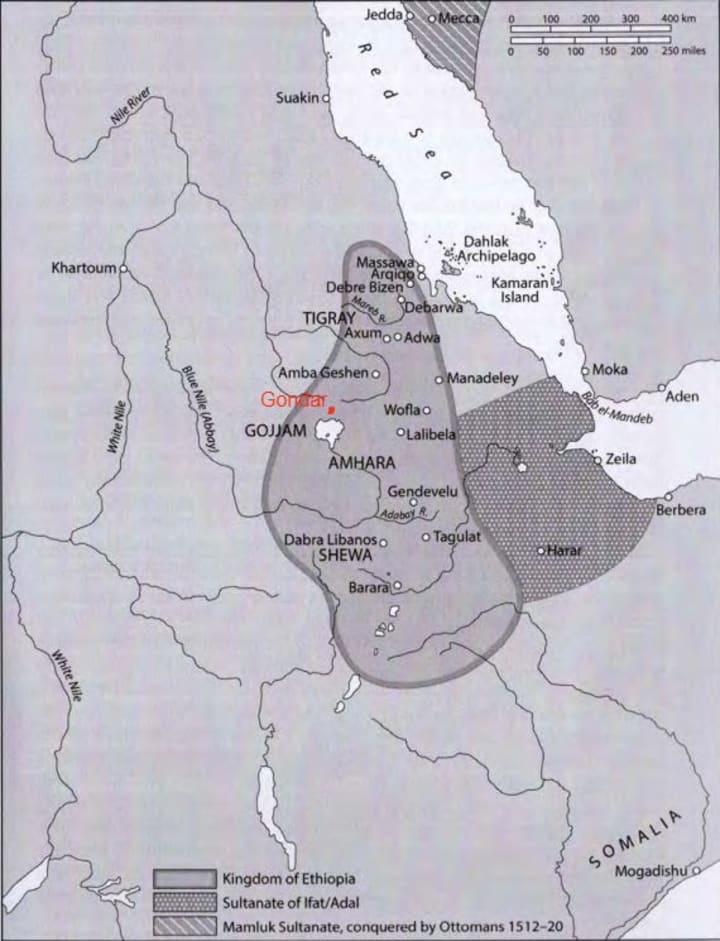

The Ethiopian Empire of Mentewab’s Era (1706 – 1773)

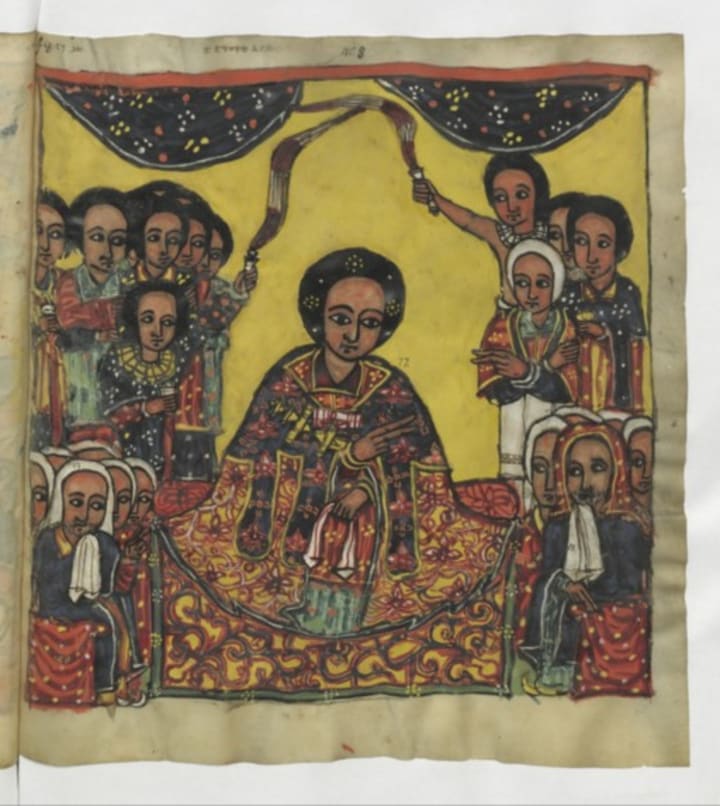

In order to properly understand Mentewab’s extraordinary life, it’s important to understand the empire she eventually came to rule. The Ethiopian Empire of the 1700s was a multi-ethnic, federalized, hereditary absolute monarchy. The ruling family of the Empire was known as the Solomonic Dynasty, who claimed direct descent not only from their Aksumite forbearers, but from the Biblical King Solomon himself.

For students of European history looking for a quick analogy, the Ethiopian Empire was quite similar to the Holy Roman Empire (HRE) in many ways. Both states had a quasi-religious emperor overseeing a collection of largely autonomous and frequently rebellious regional princes. Both states had an occasionally fraught relationship with their respective popes – the HRE had the Catholic Pope in Rome, and the Ethiopians had the Coptic Pope in Alexandria – and both states fought against Ottoman expansion.

No analogy is perfect, however. The Holy Roman Emperor was elected by his noble peers, while the Negusa Nagast (lit. king of kings) was an entirely hereditary position. While the HRE was far from its heyday under Charles V when it ruled both Spain and Central Europe, it still boasted significant territorial holdings. Meanwhile, the Ethiopian Empire was struggling to exert dominion over a small fragment of the lands once held by the Kingdom of Aksum.

By the early 1700s, the HRE had driven the Ottomans back from their borders and several allied kingdoms stood as buffers between it and any further territorial encroachments by its Muslim rival. Ethiopia in Mentewab’s day, however, was surrounded on nearly all sides by belligerent neighbors – the Sudanese Funj Sultanate to the north, Ottoman troops in the formerly Ethiopian port of Massawa, the Imamate of Awsa to the south-east, and the recently-settled Oromo kingdoms in the south-west.

The Oromos, who by the 1700s were slowly integrating themselves into the power structure of the Ethiopian Empire despite their refusal to convert wholesale to either Christianity or Islam, would play a key role in the dramatic events of Mentewab’s life. For now, however, let’s put historical context aside and focus on our main character.

Early Life and Marriage

Mentewab was born in 1706, in the Qwara province of Ethiopia. Qwara was a territory in the north-western Amhara region that included some parts of modern South Sudan. While her father was a Dejazmach (a quasi-noble military title that, in European terms, might compare to that of a landed baron or marcher lord), her true claim to nobility came from her mother, Woyzero (dame) Yenkoy. Through Woyzero Yenkoy, Mentewab could trace her bloodline back to Emperor Menas, himself a descendent of Emperor Zara Yaqob and Empress Eleni.

The story of how Mentewab met her future husband, Emperor Bakaffa, sounds like something straight out of a fairy tale. Bakaffa was well-known for traveling his domain in disguise, seeking out injustices to correct like some kind of wandering divine trickster. During one of these undercover journeys, he apparently fell ill while visiting Qwara and was nursed back to health by Mentewab.

It’s hard to know the exact chronology of the events preceding and following Mentewab’s chance meeting with Bakaffa. It seems likely that Woyzero Yenkoy was aware that Emperor Bakaffa’s first wife had died tragically on her coronation day – likely due to poisoning – and it seems equally likely that she encouraged her daughter to tend to the ailing emperor in the hopes of arranging a match. Whether Bakaffa was persuaded by Mentewab’s royal pedigree, her beauty, or a truly spontaneous act of kindness on her part is impossible to know. What is known is that Bakaffa married Mentewab in Qwara – possibly during that same visit, although that seems unlikely – on September 6, 1722. She would have been around 16 years old at the time.

A Brief Apprenticeship

Within a year of her marriage to Bakaffa, Mentewab had given birth to a son, Iyasu. By 1725 she had also given him a daughter, Walatta Takla Haymanot. Although her son was apparently sent to live in elsewhere until his accession in 1730 – likely to the mountain prison of Wehni, more on that later – Mentewab largely seems to have remained in Gondar during this period.

As one might gather from Bakaffa’s incognito escapades and the tragic death of his first wife, his brief reign was one marked by court intrigue and an increasingly fragile central government. At some point – I was not able to determine precisely when – Bakaffa suspected the imperial troops of plotting to assassinate him, so he disbanded them. In place of the standing army typical of the early Gondarine period, we see the emergence of a more feudal arrangement – where the regional kings, princes, and governors would lead their own troops to battle in collaboration with their emperor.

This was a development that would have catastrophic ripple effects.

Rise to Power

By 1728, Emperor Bakaffa had fallen grievously ill and was unable to govern. Over the next two years, Mentewab rallied a coalition of relatives from Qwara and generals loyal to Bakaffa and shaped them into an enduring power base.

That she was forming a personal power base rather than organizing a regency council for her son was made swiftly apparent when Bakaffa died in 1730. Not only did Mentewab and her supporters immediately crown her son Emperor Iyasu II, but Mentewab was crowned co-monarch and empress in her own right. Mentewab and Iyasu even adopted complimentary throne names: Mentewab was the ‘Glorifier of Light’, while Iyasu II was ‘He to Whom the Light Bows’. While some accounts state that it was Iyasu who insisted on this arrangement, given that the new emperor was 7 years old, this insistence almost certainly came at the instruction of his mother’s relatives.

Documenting Power

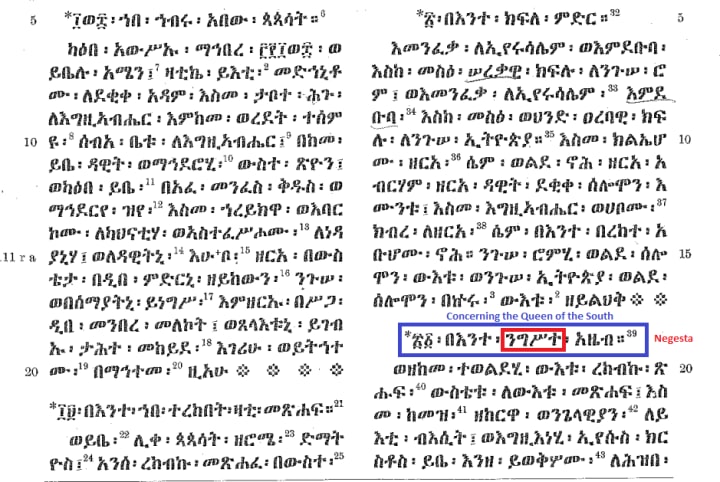

Mentewab’s distant ancestor, Empress Eleni, served as regent for her step-grandson, Dawit II, but as far as I can tell she was never crowned co-monarch. In examining the land charters issued by the Ethiopian Empire between 1314-1868, as compiled by Haddis Gebre-Meskel, I saw no evidence of Empress Eleni’s involvement in the issuance of land grants during the reigns of her husband or Dawit II. By contrast, the majority of land grants surveyed from the reigns of Iyasu II and his son, Iyo’as I are co-signed by Mentewab. While most land grants were issued under the co-monarchs’ informal titles – atse (emperor) and itege (empress-consort or dowager empress) – those that merited the emperor’s full and formal title of negusa negast saw Mentewab making use of the title of negesta (queen).

Mentewab didn’t declare herself sole ruler of Ethiopia in her own right, as Zewditu would in 1917 when she adopted the title negesta nagastat (queen of queens / queen of kings). Instead, she ruled alongside her son and grandson using a title that carried with it an association with the well-loved Eleni and – perhaps more provocatively – the legendary Queen of Sheba.

The Kebra Nagast, the Ethiopian Empire’s religious and national epic, tells us that the Queen of Sheba traveled from Ethiopia to Israel to meet with King Solomon. She later gave birth to Solomon’s son, Menelik I, in Ethiopia. When Menelik came of age, the Queen abdicated in his favor, forcing the nobles of her land to swear an oath of fealty to her son and his male descendants. The Queen’s oath was quite explicit in forbidding any woman after her from ruling the nation of Ethiopia.

It’s worth noting that the Kebra Nagast was written sometime in the 14th century – a scant century after the re-establishment of the Solomonic Dynasty – by a collection of Ethiopian priests. It should also be noted that the the Solomonic Dynasty was de-established in the first place by the sacking of Aksum by a semi-legendary queen named Gudit. While the Kebra Nagast can readily be interpreted as an Ethiopian Aeneid (ie an epic commissioned by a newly-constituted monarchy aimed at providing a religious justification for its rule), it is also important to acknowledge that it is still viewed as factual by many Ethiopian Christians to this day. Certainly, its dictates would have been considered sacrosanct by the majority of the people Mentewab sought to rule – including the part specifically forbidding her from ruling them.

Yet, Mentewab seems to have believed that a people willing to accept Eleni’s regency would be willing to accept her co-rule. The following 39 years showed that she was largely correct.

Rebellion and Rebuilding

It’s difficult to know exactly what sparked the revolt of 1732 – the only serious challenge to Mentewab’s authority during the reign of Iyasu II. Some sources argue that the revolt was led by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, who were outraged by Mentewab’s perceived violation of the Kebra Nagast’s prohibition against female rule. Other sources argue that the revolt was a dynastic struggle, an attempt by some half-forgotten prince to seize the throne and depose the child emperor. I was only able to find one source that purported to name this rival claimant – the name given was Tänśe Mammo – but I can’t find any other references to this individual, or his place in the Solomonic Dynasty.

Whomever Mentewab’s detractors were, they laid siege to the imperial capitol of Gondar for over two weeks in December of 1732. While Mentewab’s supporters eventually arrived to break the siege and defeat the rebels, the damage done to Gondar during the siege may have spurred the flurry of construction that would take place throughout the rest of Iyasu II’s reign.

That Mentewab became known as a prolific builder of churches suggests that, while Gondar might not have been besieged by an army of monks and priests, she was aware of the potential religious objections to her co-rule and sought to mitigate them through generous public works.

The Idle Emperor and the Kept Prince

Iyasu II is often characterized as an Emperor who enjoyed hunting more than ruling, who spent much of his reign pursuing buffalo, rhinoceroses, and elephants in the northern countryside. His friendly attitude toward Catholic missionaries angered the local clergy, and spending on foreign luxury goods angered his subjects.

Iyasu’s one noteworthy foray into the realm of warfare was an unmitigated disaster for Ethiopia and his reputation. In 1738, a 15-year-old Iyasu II led his army in an invasion of the Funj Sultanate. While Iyasu led his vanguard looting and pillaging villages along the Nile, the main bulk of his army – some 18,000 warriors – were slaughtered in an ambush. While Iyasu tried to paint the campaign as a success on account of the goods and livestock captured in his raids, his subjects and noble peers could not fail to notice that his army had returned 18,000 men smaller.

That Iyasu’s reign – despite his military incompetence, disinterest in ruling, and several natural disasters – was remembered as largely peaceful and prosperous is a credit to Mentewab’s able hand. She secured the loyalty of the imperial nobility with generous land grants, and ensured relative peace with the Oromos by marrying her son to the daughter of an Oromo notable. While these policies are easy to criticize in hindsight, the decentralized military she inherited from her husband had just been dealt a crippling blow by her son – bribing and assimilating potential rivals may have been her only means of avoiding conflict.

The stability of this period is even more remarkable considering that Mentewab was engaged in a salacious, well-known love affair with one of Emperor Iyasu’s cousins, also named Iyasu. Not much is known about Melmal Iyasu (Iyasu the Kept), as he came to be known, save that he was the son of Bakaffa’s sister, Romanework. Melmal Iyasu was consistently described as ‘much’ younger than Mentewab, but I have not been able to find any sources that purport to establish his date of birth or when he and Mentewab met. Perhaps someone with more knowledge of Ethiopian cultural norms surrounding marriage, adulthood, and gender could piece together a reasonably accurate guess for the age gap, but that someone isn’t me.

All we can say for certain is that at least a significant portion of their love affair had to have been conducted when Melmal Iyasu was of post-pubescent age, as he and Mentewab had three daughters together. While the sources tell us that Iyasu II was fond of his half-sisters, they also agree that he despised his mother’s lover. It should therefore come as no surprise that, when Melmal Iyasu perished after falling from a cliff near Lake Tana in 1742, most sources blamed Iyasu II for his demise. When Iyasu II died of a sudden illness 13 years later, at the age of 32, it was generally believed that he had been poisoned by one of Melmal Iyasu’s relations.

Whatever Mentewab might have known or suspected about the death of her lover, she’s said to have been deeply saddened by the loss of her son. The royal chroniclers state that she threatened to retire from imperial administration to the cloister of the church she built, but that she was convinced by her supporters to assume the role of regent for her infant grandson, crowned Iyo’as I.

The crowning of an infant, nearly always a controversial act, was rendered even more so by the fact that Iyo’as was technically Iyasu II’s youngest son.

The Daughters-in-Law

The sources I have available to me refer to Iyasu II’s first wife simply as ‘an Amhara woman.’ This Amhara woman bore three sons by Iyasu II, and one daughter. These same sources suggest that the Amharic woman insisted that she be involved in government alongside her husband, and that Mentewab exiled her and her sons to the royal prison of Wehni as punishment for her ambition.

While this interpretation of events is possible, I don’t think it’s the most likely. After all, if Iyasu II’s first wife was of such obscure origins that her name is not even remembered in the chronicles – despite the fact that two of her grandsons and one great-grandson would go on to reign as emperors – I very much doubt that she had the political clout to even think of challenging Mentewab. More likely than not, she was chosen by Mentewab specifically for her lack of family connections.

Moreover, the imprisonment of royal heirs and male relations was commonplace during this time in Ethiopia’s history. Bakaffa is known to have spent some time in Wehni before inheriting the throne, and Iyasu likely did as well. Therefore, sending Iyasu II’s first wife and her children to Wehni would have been a perfectly ordinary turn of events. The narrative painting the Amhara woman as a victim of Mentewab’s ruthless scheming is likely a backwards-facing projection of her well-documented and disastrous rivalry with Iyasu II’s second wife, Wubit (later christened Bersabeh).

Wubit, unlike the nameless Amhara woman, had a powerful Oromo dynasty at her back. Mentewab had clearly arranged Iyasu II’s marriage to Wubit with the aim of expanding imperial authority through an alliance with her daughter-in-law’s family. Instead, she found herself at confronted with a rival power bloc headed by a young woman determined to follow her footsteps.

The Final Reign

When Iyasu II died, precedent suggested that his court had two equally-unpalatable choices: They could sideline Wubit, risk war with her powerful relations, and put the children of Iyasu II’s first marriage on the throne; or they could appoint Wubit regent and co-monarch with her son, as they had done with Mentewab, and risk an Oromo takeover of imperial government. So, they chose a third option, and declared a reluctant Mentewab regent and co-monarch with her grandson.

When we consider the question of whether Mentewab was a rank hypocrite for opposing Wubit’s rise, it’s important to remember that Mentewab achieved her elevation with the support and consent of the empire’s notables. Even absent Mentewab’s candidacy, the predominantly Amharic and Tigrayan nobility of the Gondarine period would never have agreed to support an Oromo woman as regent.

That Mentewab was chosen as regent rather than her well-regarded brother, Ras Wolde Leul, or the powerful prince of Tigray, Ras Mikael Sehul, is a testament to her enduring influence. That the accession of a one-year-old, half-foreign infant to the throne did not immediately occasion civil war – especially in a state that had long lacked a strong, centralized military – is a further testament to Mentewab’s political acumen.

With her brother acting as her trusted right hand, Mentewab bought her realm another 12 years of relative peace and stability. Damot was the only province to rise in opposition to Iyo’as I, but their rebellion was swiftly crushed by another of Mentewab’s brothers, Eshte. The provincial governorship of Damot was thereafter given to one of Mentewab’s allies, Waragna Ayo.

However, as Iyo’as grew older, the seeds of conflict began to sprout. Much to the horror of Mentewab’s relations and allies, her grandson preferred to speak Oromo rather than Amharic, and grew to generally favor the advice of his Oromo relations. Mentewab’s allies began to fear that their privileges and influence would be undermined – if not stripped away piecemeal – by their Oromo rivals. Wubit’s allies grew more emboldened to expand their holdings and power as the emperor’s favor became known.

By March of 1767, Ras Wolde Leul and Waragna Ayo had died and conflict finally exploded out into the open. A dispute over who would succeed Waragna Ayo as governor of Damot rapidly escalated into a war between his son, Ya Mariam Bariaw, and the emperor's Oromo uncle, Birale. Mentewab seems to have supported her son-in-law, Ya Mariam Bariaw – he had married Woyerzo Aster in 1760 – while Iyo’as I and Wubit favored Birale.

When Birale was killed following the battle for Begemder’s governorship to Ya Mariam Bariaw – despite orders that he be spared – Ras Mikael Sehul was called upon to resolve the conflict. Exactly who called on Ras Mikael for help seems to be a matter of debate. Some sources suggest that it was Iyo’as, while others claim that Mentewab issued the summons. Perhaps the increasingly estranged grandmother and grandson found some common ground, and felt that the most powerful lord in their domain was well-positioned to put an end to the conflict.

Regardless of who reached out to Ras Mikael, both Mentewab and Iyo’as would soon come to regret his involvement.

Accounts tell us that Ras Mikael held the emperor in contempt and was sympathetic toward Ya Mariam Bariaw’s cause. Nevertheless, Ras Mikael agreed to lead an expedition against Ya Mariam Bariaw in the emperor’s name. Ya Mariam Bariaw retreated to the furthest reaches of his province, but was eventually forced to give battle – a battle he lost in spectacular fashion. The captured Ya Mariam Bariaw was brought before Iyo’as I, who permitted his uncle and Birale’s brother, Lubo, to kill Ya Mariam Bariaw.

It’s difficult to know whether Ras Mikael acted next out of righteous indignation at the emperor’s callous treatment of noble prisoners, or out of a sense of self-preservation in the face of Oromo ascendency. What is known is that Ras Mikael Sehul deposed Iyo’as I on May 7th, 1769 and had him murdered one week later.

The death of Mentewab’s grandson, whatever their political differences had been in life, seems to have finally broken her. She buried Iyo’as next to her son, Iyasu, at her church at Qusquam, and retreated from public life. This time, her retirement was respected by both her adversaries and allies alike. She died four years later, on June 27, 1773. Between her retirement and her death, Ras Mikael Sehul had married Woyzero Aster, and three new emperors had been placed on the throne by competing noble factions, only to be removed in their turn.

Conclusions

History is generally unkind to rulers whose reigns precede calamity. The end of Mentewab’s public life marked the beginning of nearly a century of civil war – an era that came to be known as the Zemene Mesafint (Era of Princes / Era of Judges). Given Ethiopia’s history with calamitous queens like Gudit, and given Mentewab’s perceived involvement in the decentralization that made the Zemene Mesafint possible, one would expect the chronicles to scorn and curse her memory.

Instead, the general consensus seems to have been that Mentewab was an extraordinary woman who held off the complete dissolution of imperial authority for nearly 4 decades.

About the Creator

T. A. Bres

A writer and aspiring author hoping to build an audience by filling this page with short stories, video game reviews/rants, history infodumps, and comparative mythology conspiracy theories.

Come find me @tabrescia.bsky.social

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.