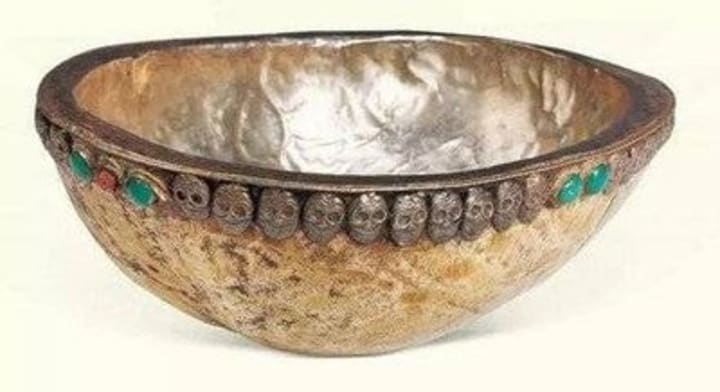

Kabala bowl - a bowl made of skulls from the Tibetan people of China

The Kapala bowl, also known as the Toba, is a skull bowl made of human skull, crystal and gold. It is also called the inner skull vessel and the human head vessel. It is a ritual implement for the initiation ceremony of the "Supreme Yoga Tantra" and is one of the ritual implements of Tibetan Buddhism. It is popular in Tibetan Tantric Buddhism to use human bones to make various ritual instruments. However, the skull for making the skull bowl must come from a successful lama and must be made according to his or her last wishes. The purpose of initiation is to make practitioners wise and cleanse them of all impurities. Some people also say that it helps people break their ego. When Tantric practitioners hold an initiation ceremony, holy water is placed in the initiation pot and wine is placed in the head vessel. Senior monks sprinkle the holy water on the practitioner's head and let him drink the wine, and then grant him the tantric teachings. The Kapal bowl (Toba) is a practice offering for many Vajrayana practitioners. The main deity, the dakini protector, usually holds this bowl in his left hand. The bowl is used to hold nectar, which is usually represented by wine by practitioners, and in thangkas, it is often represented by red blood. Generally, practitioners use a toba as an offering vessel, which is filled with white wine or red wine, and is used to offer to the deity, the dakini, or the protector. It is also used for self-offering during practice. For specific usage methods, please refer to the Dharma text. It is a must-have item for Vajrayana practitioners. Toba/skull vessel/kapalala is one of the common ritual implements in Tibetan Tantric practice. In the past, it was usually made of human skulls. The human skulls are made to represent impermanence, and the edges are inlaid with silver or gold. There is a lid on the top and a base below. The base is triangular and decorated with patterns representing flames. The skull vessel represents the nectar of offerings, or represents all the merits, virtues, and wisdom. The Kabala offering bowl is a bowl-shaped offering vessel made of gold, silver, copper, iron, jade, agate, monkey bones, etc. according to strict dimensions and rituals of Tibetan Tantric Buddhism. It is mainly used on the altar to hold various offerings, such as nectar, nectar pills, seven treasures, Tibetan incense, barley wine, ghee, etc. Its use is different from the Kabala bowl for initiation nectar, but its special significance is the same. The skull bowl is not only used as a tantric ritual implement, but also an important offering vessel. It is worshipped as a precious relic and is only offered in the temple of the guardian deity and the meditation room of the tantric master or practitioner, or in the tantric room. It is not seen in the main hall of the temple. Buddhists have great respect for it, believing that it is "the result of the immeasurable six paramitas" and the result of the practice of precepts, concentration and wisdom of the monks. It is not comparable to the skulls of ordinary people. Moreover, because of the practice, most skull bowls have "hidden words". The skull bowl is also made of other materials and is given the meaning of ensuring safety and praying for good luck. The Kapala bowl in the Outer Eight Temples of Chengde is a fully decorated skull bowl, with a base length of 19.6 cm, a width of 19.6 cm, and a total height of 24.2 cm. This bowl is wrapped in gold, silver, copper and other metals, and has exquisite patterns. It is very ornamental and one of the few skull bowls that still exist. This Kapala bowl is silver-gilt and engraved, and consists of three parts: the bowl cover, the bowl body and the bowl holder. The lid button is in the shape of a flame inlaid with gems, and there are four lotus flowers engraved on the bowl cover, surrounding the lid button. The lid is also engraved with the auspicious eight treasures: wheel, snail, umbrella, lid, flower, pot, fish, and long, which means good luck. The upper part of the bowl holder is a round pedestal, with a gilded waist and a circle of turquoise inlaid. The three sides are decorated with human heads, and the surroundings and the surface of the bowl holder base are decorated with lotus flowers, and the lotus is gilded. The bottom plate is engraved with Manchu, Chinese, Mongolian and Tibetan, and the content is: "Praise of the Ancient Kapala Offering Bowl. I heard that in the past, the Buddha offered his head as sandalwood to save all living beings in the bright moon. The left side was smeared with sandalwood, and the right side was cut with a sharp knife. These two people did not distinguish between the Five Seals and the Tripitaka. Many ancient sages used this example. They offered their heads in the ten directions and ten colors as one to transform all. They shared the common people's compassion and aspirations and the saints' mercy. This is the true offering. Those who have no offerings are praised for the rapport and paraprajna. The emperor praised it in the Jiaping month of the Renzi year of Qianlong." The entire Kapala bowl is made of fine materials, exquisitely made, and sophisticated in workmanship, and the intention of cherishing it is very obvious. The unique features of some Tantric Kabala bowls: There is an artificial hole at the back of the top of the Kabala bowl called Powa hole. The reason for its formation is detailed in Powa method. There are very few naturally formed holes in the skull bowls called "Eye of the Universe". In the eyes of some lamas, they are a symbol that the practitioner's soul has reached the sky, which is extremely rare and special. The famous skull bowl During the Yuan Dynasty, Tibetan Lamaist monk Yang Lianzhenjia excavated the six tombs of the Southern Song Dynasty. Seeing that the body of Emperor Lizong of the Song Dynasty was well preserved, he hung the body upside down on a tree for three days, which resulted in mercury leaking out. He also presented Emperor Lizong's skull to the imperial teacher Phagpa as a drinking vessel, which was the skull bowl. This was something that Emperor Lizong of the Song Dynasty never expected during his lifetime. The skull of Emperor Lizong was not found until Zhu Yuanzhang conquered Dadu, and Zhu Yuanzhang ordered people to rebury the skull of Emperor Lizong at the site of the Song Tombs and repair the destroyed tombs.

The Kapala: A Sacred Vessel of Tibetan Buddhist Tantra

The kapala, a ritual cup fashioned from a human skull, stands as one of the most enigmatic and symbolically charged artifacts in Vajrayana Buddhism. Originating in 8th-century Indian Tantric traditions and later adopted into Tibetan Buddhist practice, this macabre yet sacred object embodies paradoxical truths about life, death, and spiritual transcendence. Unlike ordinary religious implements, the kapala forces confrontations with mortality while simultaneously pointing toward liberation from cyclic existence (samsara).

Historical Context

Early textual references appear in the Hevajra Tantra, where skull-cups serve as crucial tools in chöd rituals – meditative practices designed to dismantle egoic attachments. When Buddhism migrated to Tibet, the kapala became integrated with Bon shamanistic traditions that already revered skulls as vessels for ancestral wisdom. By the 11th century, master yogis like Milarepa were depicted carrying kapalas, cementing their status among enlightened beings who had transcended societal taboos.

Crafting the Vessel

Traditional artisans follow strict protocols. Skulls ideally come from accomplished practitioners who voluntarily bequeath their remains – a tradition paralleling Tibetan sky burials where offering one’s body symbolizes non-attachment. The skull undergoes ritual purification: brain matter removed through the foramen magnum, residual tissue decomposed using herbal mixtures, and the bone polished with consecrated oils. A repoussé silver or gilt copper stand often adorns the base, engraved with vajra motifs and mantra syllables (Om Ah Hum). The finished kapala measures approximately 15-20cm in diameter, its cranium curvature forming a natural bowl.

Ritual Symbolism

Within Tantric iconography, the kapala operates on multiple esoteric levels:

Memento Mori: As a relic of impermanence (anitya), it confronts practitioners with the inevitability of death.

Alchemical Crucible: In ganachakra feasts, it holds sacramental wine transformed into "nectar of wisdom" (amrita), representing the transmutation of desire into enlightenment.

Cosmic Map: The cranial sutures mirror sacred geography – the four plates symbolizing continents in Buddhist cosmology, the coronal suture as Mount Meru’s axis.

Non-Dual Embodiment: Holding both polluted (death) and pure (wisdom) aspects, it manifests the Tantric union of opposites.

Deity Associations

Specific deities demand kapala use:

Chakrasamvara: The wrathful yidam holds a kapala filled with blood, representing the subjugation of ego.

Vajrayogini: Her kapala overflows with bliss-wisdom, challenging dualistic perceptions of purity.

Mahakala: The protector deity uses it to collect obstructing forces, later transmuting them into compassion.

Artistic Evolution

17th-century Nepalese-Tibetan artisans elevated kapalas into masterpieces. The "Flaming Pearl" variant features a skull encased in scrolling gold flames symbolizing wisdom’s transformative power. Imperial Chinese records (Qianlong era) document jewel-encrusted kapalas gifted to Tibetan lamas, blending Buddhist symbology with Qing dynasty aesthetics. Modern forensic studies reveal remarkable craftsmanship – 18th-century specimens show precise drilling techniques to create mantra-inscribed silver linings without cracking the cranium.

Modern Controversies

Post-1959 diaspora practices sparked ethical debates. Authentic consecrated kapalas became increasingly rare, leading to:

Substitutes using coconut shells or metal replicas in exiled communities

Black market exploitation of unclaimed Himalayan burial remains

Neo-Tantric reinterpretations divorcing the object from its doctrinal context

Western museums now grapple with display ethics. The British Museum’s 2022 exhibition curated kapalas alongside MRI scans of meditating monks’ brains, emphasizing their enduring psychological resonance.

Enduring Relevance

The kapala’s power lies in its irreducible ambiguity – simultaneously a grisly corpse fragment and a sublime mandala. As contemporary Buddhists reinterpret ancient rites, this skull-cup continues to challenge materialist worldviews. In the words of Dzogchen master Dudjom Lingpa: "To drink from the kapala is to swallow the universe’s truth: all phenomena are empty, yet miraculously present."

Its enduring presence in Himalayan art and meditation practice confirms that this most unsettling of sacred vessels remains indispensable for those walking the Tantric path – a stark reminder that enlightenment often dwells where conventional minds fear to gaze.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.