History

The Rise and Transformation of Ancient Civilizations

History is not a straight road but a winding river, shaped by countless tributaries of human action, innovation, and conflict. From the first mud-brick cities on the banks of the Tigris to the marble forums of Rome, ancient civilizations emerged, thrived, and eventually transformed into something new. Their stories are the foundation of our modern world — in language, politics, architecture, and ideas.

The Birth of Cities

Around 10,000 BCE, the last Ice Age retreated, and humans found themselves in a world rich with opportunity. They had spent tens of thousands of years as nomadic hunter-gatherers, but warming climates and fertile valleys created a new possibility: agriculture.

The Fertile Crescent — stretching across modern-day Iraq, Syria, and Turkey — was one of the first places where farming took hold. The domestication of wheat, barley, sheep, and goats allowed humans to settle permanently. Villages such as Jericho and Çatalhöyük appeared, but over centuries, these settlements evolved into something much larger: cities.

By 3000 BCE, in the region of Mesopotamia, the Sumerians had built urban centers like Uruk and Ur, complete with temples (ziggurats), marketplaces, and organized governments. Writing — first in pictographs, then in cuneiform — emerged as a revolutionary technology, allowing for trade records, literature, and laws.

Empires and Ambition

While Mesopotamia’s cities flourished, other centers of civilization rose. Along the Nile, the Egyptian civilization unified under powerful pharaohs around 3100 BCE. The predictable flooding of the Nile ensured agricultural stability, allowing the Egyptians to focus on monumental architecture like the Pyramids of Giza. Religion and governance intertwined so tightly that the pharaoh was considered divine, ruling over a centralized state for millennia.

Farther east, the Indus Valley Civilization (2600–1900 BCE) developed in present-day Pakistan and northwest India. Cities like Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro displayed astonishing urban planning: straight streets, drainage systems, and standardized weights. While their writing remains undeciphered, their archaeological remains reveal a culture both technologically advanced and remarkably egalitarian.

By the time China’s first dynasties emerged around 2100 BCE, the pattern of centralized rule, agriculture-based economies, and urban centers had become the backbone of human civilization. The Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties laid the foundations for Chinese political philosophy, bureaucracy, and culture.

The Age of Bronze and Iron

Advances in metallurgy marked turning points in history. Bronze tools and weapons gave early states a military and economic edge, but it was the transition to iron around 1200 BCE that reshaped the ancient world.

In the eastern Mediterranean, the Hittites mastered ironworking, giving them a decisive advantage in warfare. The spread of iron technology coincided with a period of upheaval known as the Late Bronze Age Collapse (circa 1200 BCE), when many established civilizations — from the Mycenaean Greeks to the Hittites themselves — fell to mysterious invaders, natural disasters, and economic instability.

From the ashes, new powers rose. The Neo-Assyrian Empire built the first true military superpower, using iron weaponry, siege engines, and a professional army to conquer a vast territory from Egypt to Persia. The Phoenicians, meanwhile, turned to the sea, developing trade networks across the Mediterranean and introducing the alphabet that would later inspire Greek and Latin scripts.

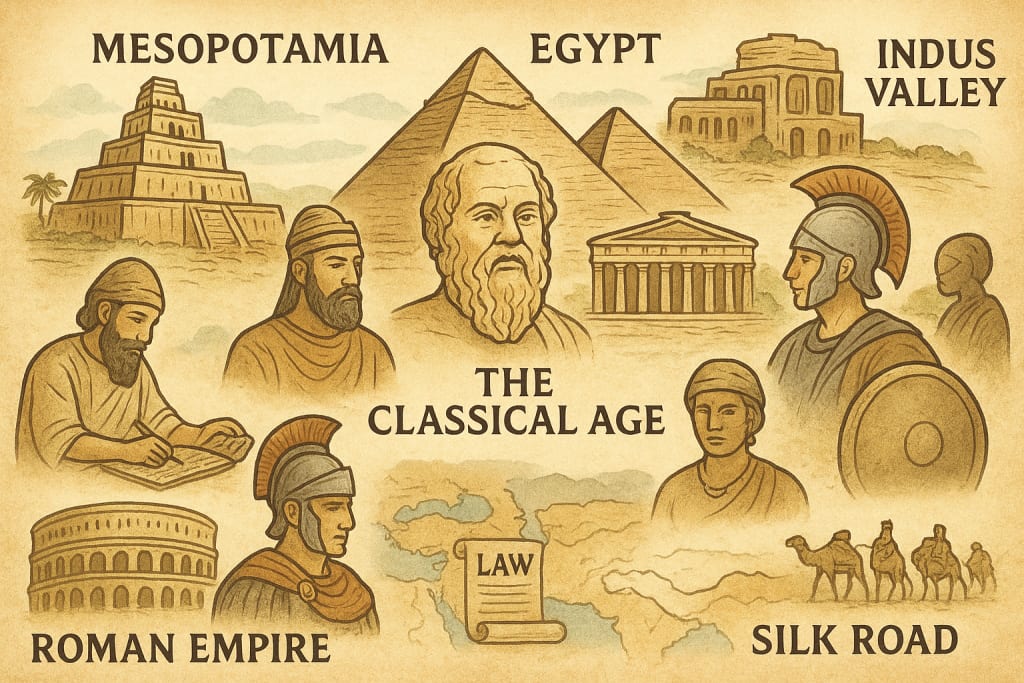

The Classical Age: Greece and Rome

By the 5th century BCE, the Greek world had entered its classical period. While never unified under one government, the Greek city-states — notably Athens and Sparta — became laboratories of political experimentation. Athens developed democracy (though limited to free male citizens), nurtured philosophy through thinkers like Socrates and Plato, and celebrated human achievement in art and drama. Sparta, in contrast, prioritized military discipline and austere living.

The threat of the Persian Empire united these rival cities temporarily, leading to legendary battles at Marathon, Thermopylae, and Salamis. After the wars, Athens experienced a “Golden Age,” but internal conflicts — most notably the Peloponnesian War — weakened Greece.

Into this fractured world stepped Alexander the Great (356–323 BCE), who forged one of the largest empires in history, stretching from Greece to India. His campaigns spread Greek culture across the Near East in a process known as Hellenization, blending Eastern and Western traditions.

While Greece fragmented after Alexander’s death, Rome was on the rise. Initially a small city-state, the Roman Republic expanded through military conquest and strategic alliances. By the 1st century BCE, internal tensions and civil wars transformed it into the Roman Empire under Augustus.

Rome’s power rested on engineering brilliance — roads, aqueducts, and fortified cities — as well as legal systems that influenced modern law. For centuries, the empire controlled the Mediterranean world, earning the nickname Mare Nostrum (“Our Sea”).

Religion and Cultural Exchange

Ancient civilizations were also crucibles for religious and philosophical thought. In India, Hinduism developed alongside Buddhism, founded by Siddhartha Gautama in the 5th century BCE. In China, Confucianism and Daoism shaped political and moral life. In the Middle East, Judaism emerged as one of the first monotheistic faiths, influencing Christianity and Islam.

Trade routes like the Silk Road connected these worlds, allowing goods, ideas, and technologies to flow between civilizations. Silk and spices traveled west, while glassware and metallurgy techniques moved east. Cultural exchange was constant, even in times of war.

Decline and Transformation

No civilization lasts forever. By the 3rd century CE, the Roman Empire faced internal decay, economic troubles, and external pressures from migrating tribes. In 476 CE, the Western Roman Empire formally collapsed, though the Eastern half — the Byzantine Empire — endured for another thousand years.

In China, dynasties rose and fell in cycles, following what historians call the “Mandate of Heaven” — the belief that rulers governed with divine approval, which could be withdrawn during periods of corruption or disaster.

Some civilizations, like Egypt, persisted through foreign conquest, adapting to new rulers while preserving cultural traditions. Others, like the Maya in Central America, experienced mysterious declines long before European contact, possibly due to environmental stress and political instability.

The Legacy of the Ancients

Although many ancient civilizations faded, their legacies live on. Our alphabets, legal codes, architectural styles, and political philosophies all have roots in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, Rome, China, and India. The idea that humans can shape their environment, govern themselves, and record their achievements is one of the most enduring gifts of the ancient world.

In the end, history is not simply a record of dates and names. It is the story of how countless generations built the foundations on which we stand. And while the empires of the past have crumbled into dust, the ideas they created continue to shape our present — and our future.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.