History of the Cigar store Indian.

A piece of Americana

Most Americans know of the wooden cigar store Indian, and have seen one in front of a cigar store, liquor store, trading post, or somewhere. It is a piece of Americana folk art. But do you know anything about it? Who makes them, where they are made, why they are made? If not, read on.

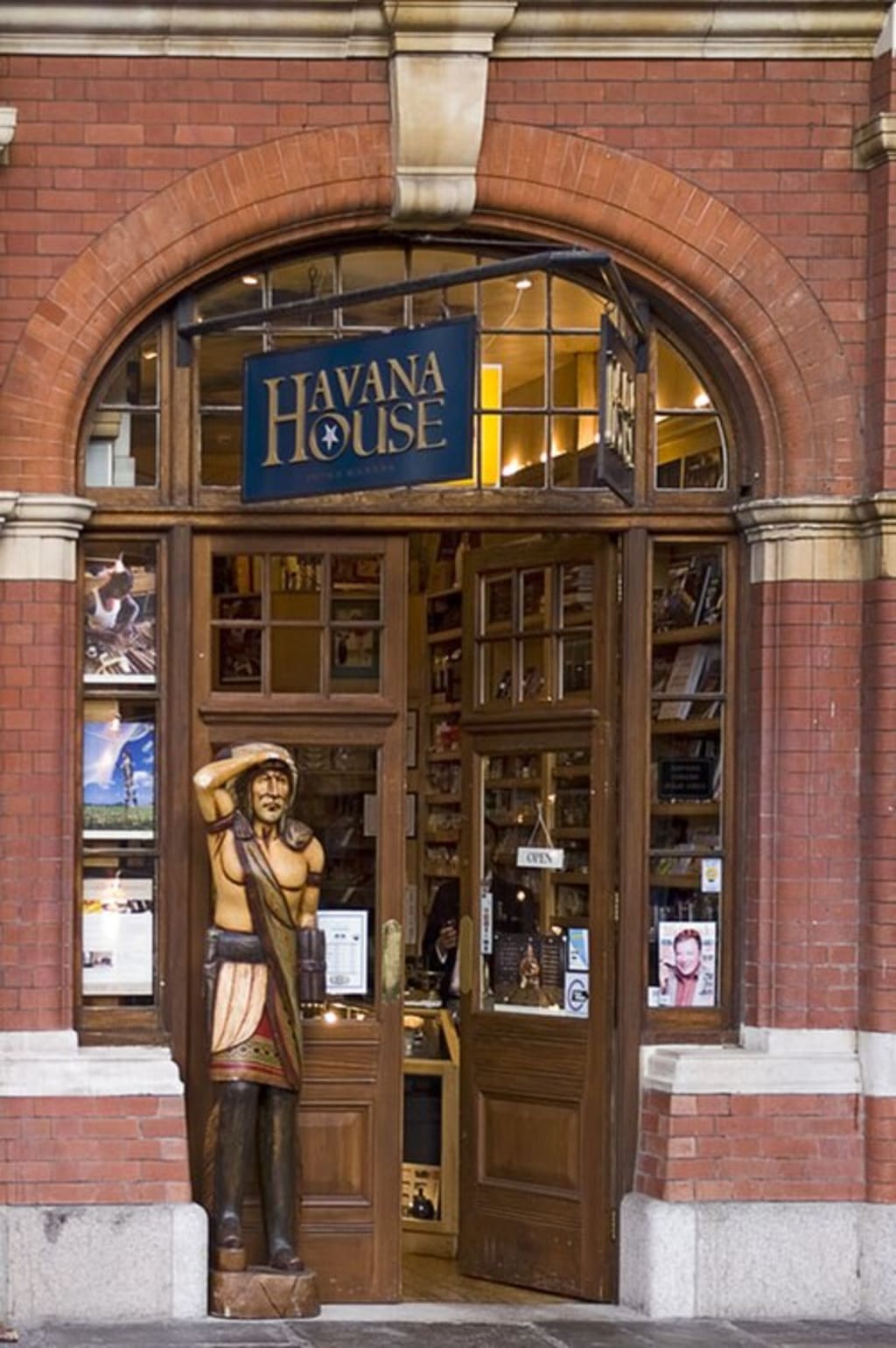

In the 1600’s, as ships from America began to bring tobacco to England, cigar shop owners displayed carved Indians in front of their stores as a symbol of the introduction to tobacco by Native Americans. American Indians were the original subjects for the figures, because they had, after all, introduced Christopher Columbus and his crew to tobacco.

The early carvings were made by artisans who had never seen a Native American. Therefore, the statues looked more like black men or “Virginians” with feathered headdresses wearing kilts made of tobacco Leaves. Eventually, the European tobacco shop figure began to take on a more “authentic” look. By the late 18thcentury, the statue had become completely “Indian” in the Americas.

By the 1850s, American cities were growing in size and there were more tobacco stores. This is the time when the cigar store Indian began appearing on American streets. Due to the level of illiteracy and a large non-English speaking population, shop owners used figures, emblems, and symbols to advertise their wares. Barbershops displayed the iconic barbershop red and white poles and tobaccos shops placed the wooden Indian in front of the store as an advertisement.

Most of the men who carved cigar store Indians came from a shipbuilding background where they specialized in sculpting wooden figureheads for each ship. These carvings—figureheads and store carvings–were generally out of a single piece of wood, (An outstretched arm sometimes had to be attached separately.) Everything from the selection of the material to the artistry of the carving made a difference.

Because there were not many carvers, cigar store Indians were not widely available until the 1850s when the shipping industry began to switch from wooden ships to ironclad steam vessels, and the ironclads had no need for figureheads.

When the ship-carving business dried up, the artists were delighted to turn to carvings for retail establishments.Most of the men who carved cigar store Indians came from a shipbuilding background where they specialized in sculpting decorative wooden figureheads for a prow of a ship. Generally, the figureheads and store sculptures were from a single piece of wood. The cigar store Indian statues are often three-dimensional wooden carvings commonly made of white pine several feet tall, some life-sized and some as tall as seven feet.

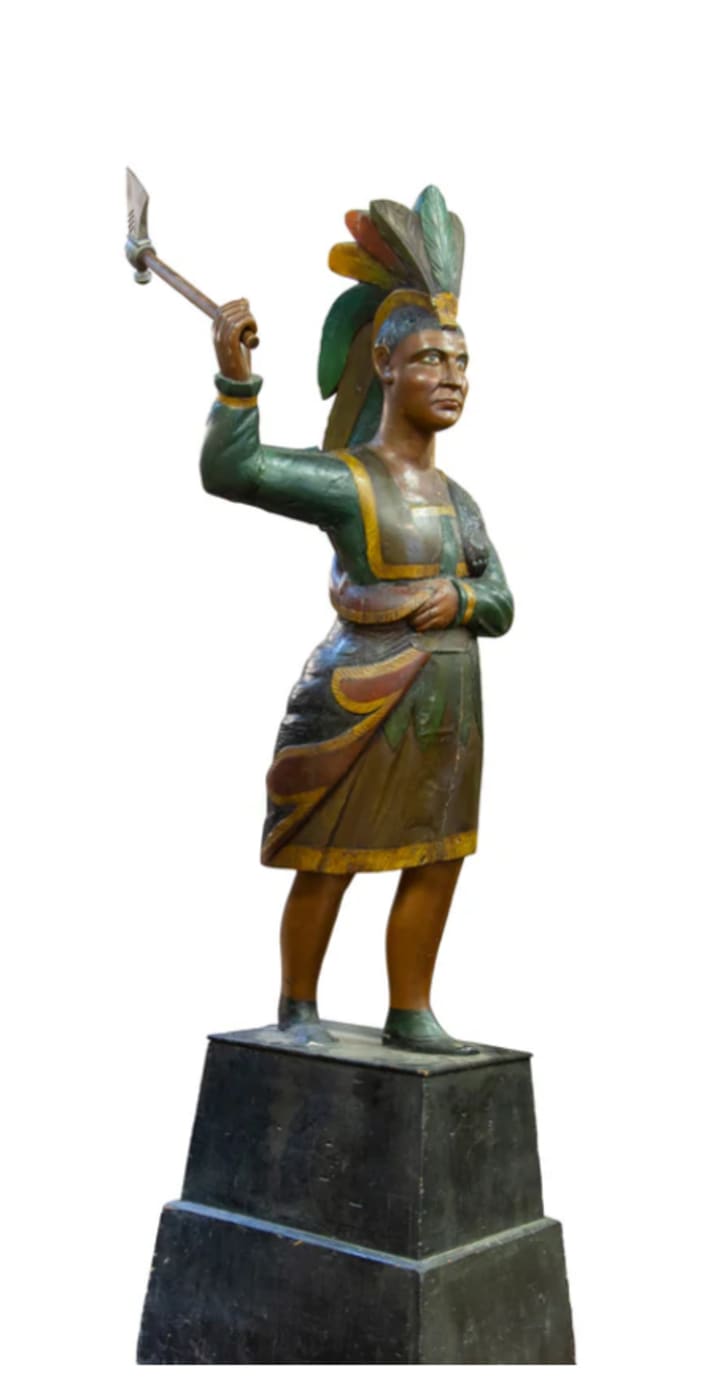

The more expensive and rare metal statues were mostly made of zinc. Both metal and wood statues were hand painted. The most common types of statues are the “noble savage” (with a passive stance and stoic expression) and the “warrior” (brandishing a weapon).

Most statues held tobacco or had leaves painted on their clothing. To give the statues personality, local townspeople would give them names. For instance, in Reading, Pennsylvania, the cigar store Indian was known as Old Eagle Eye. Chief Blackhawk lived on the streets of Louisville, Kentucky. Created in 1849, Chief Semloh resided in San Francisco and lasted on the streets until the 1906 earthquake.

Eventually , the cigar store Indian would lose its popularity with retailers. Around 1890, the city streets in America were becoming increasingly populated. By 1911, cities began passing obstruction laws requiring at least two feet of open space in front of each store. Later, other issues, including higher manufacturing costs of the statues, restrictions on tobacco advertising, and an increase of racial sensitivity helped lead to the demise in popularity of the iconic figures.

Today, a cigar store Indian in its’ original condition is a rare find. Tobacco shop owners began expanding their product lines and many statues were tossed. Also, many cigar stores’ Indian carvings were destroyed at scrap drives for metal and wood during World War I and World War II. Viewed as folk art, those that still exist tend to be in museum collections or in private hands.

These days the best of the wooden cigar store Indian sculptures can sell for as much as $100,000. A rare five-foot cigar store Indian figure with original paint and beautifully carved in the 1880s by the renowned artisan Samuel Robb, sold for $94,400 at auction in 2012. Regardless, the Cigar Store Indian has a permanent position in the history of cigars and cigar shops. Not every tobacconist wanted an Indian for the shop. Another popular figure for tobacco stores were Turks wearing turbans, soldiers in uniform, or a fashionable lady.

The statues used to mark various stores took on personalities given them by the townspeople. In Reading, Pennsylvania, the cigar store Indian was known as Old Eagle Eye. Chief Blackhawk, carrying a warrior’s club and a lion skin, lived on the streets of Louisville, Kentucky. Chief Semloh was created in 1849 in San Francisco, and he lasted on the streets there until the San Francisco earthquake in 1906. Semloh was removed from the street, but someone took an interest in tinkering with him. They made it so he could blow smoke through his mouth and talk through a loudspeaker in his chest.

Famous Carvers of Cigar Store Indians

Two of the more famous carvers of the nineteenth century were Julius Melchers (1829-1908) and Samuel Robb (1851-1928). Melchers was a German-born sculptor

Samuel Robb was born into a family of Scottish ship carvers, and he grew up in Brooklyn, New York. In his teens he apprenticed to a shipbuilder, and then took a job with a wood-carver where he further perfected his art. At night Robb took classes, first at the National Academy of Design, and then at Cooper Union. In 1876 (when he was 25) he opened his own shop in New York City, and it became the largest shop of its kind during the 19th century. Robb became highly sought-after carver for his ability to create a wide variety of figures ranging from cigar store Indians to circus wagons and ventriloquist dummies. Because he was highly sought-after he eventually opened a second workshop.

Cigar store figures are now viewed as folk art, and some models have become collector's items, drawing prices up to $500,000. Modern replicas of cigar store Indians are still made for sale, some as cheap as $600.

People within the Native American community often view such likenesses as offensive for several reasons. Some object because they are used to promote tobacco use as recreational instead of ceremonial. Others object that they perpetuate a "noble savage" or "Indian princess" caricature or inauthentic stereotypes of Native people, implying that modern individuals "are still living in tepees, that we still wear war bonnets and beads,"drawing parallels to the African-American lawn jockey.

New York carver John L. Cromwell, who had made his name largely as a maker of ship figureheads, was capitalizing on what had become, by the mid 1800s, a conventional marketing idea: the commercial association of American Indians and tobacco. Thousands of these tall, sculptural figures were created in America during the 19th and early 20th centuries for the hugely profitable tobacco trade. And although not all tobacco figures portrayed Native American men and women, as folk art appraiser Allan Katz explained, "The reason for it is the Indians taught the settlers how to raise, plant and harvest tobacco."

The figures were a product of their time, a period fraught with prejudice against indigenous peoples. The statues helped to invent and then reinforce the quintessential stereotype of an “authentic” Native American by often depicting figures with bronze-colored skin wearing feathered headdresses, long fringed skirts or shirts, and moccasins. Critics have compared the characters to racist lawn ornaments of black jockeys. Two of the more common types of Indian cigar statues portray the “noble savage” with a stoic expression and passive stance; or the warrior, who brandishes a weapon he’s poised to use.

In their day, these silent statues were effective communicators, meant to indicate to all — including the illiterate and non-English speakers — what was for sale. What they represent today to citizens of the 21st century is a more complicated message, eliciting both appreciation and disapproval.

About the Creator

Guy lynn

born and raised in Southern Rhodesia, a British colony in Southern CentralAfrica.I lived in South Africa during the 1970’s, on the south coast,Natal .Emigrated to the U.S.A. In 1980, specifically The San Francisco Bay Area, California.

Comments (1)

Wow . That is awesome.