Comparison of European colonialism in Asia

The French attitude towards colonial subjects was, in some respects, very different from that of their British rivals. The idealistic French sought not only to dominate their colonial possessions, but they remained, like the Dutch and Portuguese, steeped in resource and economic motives.

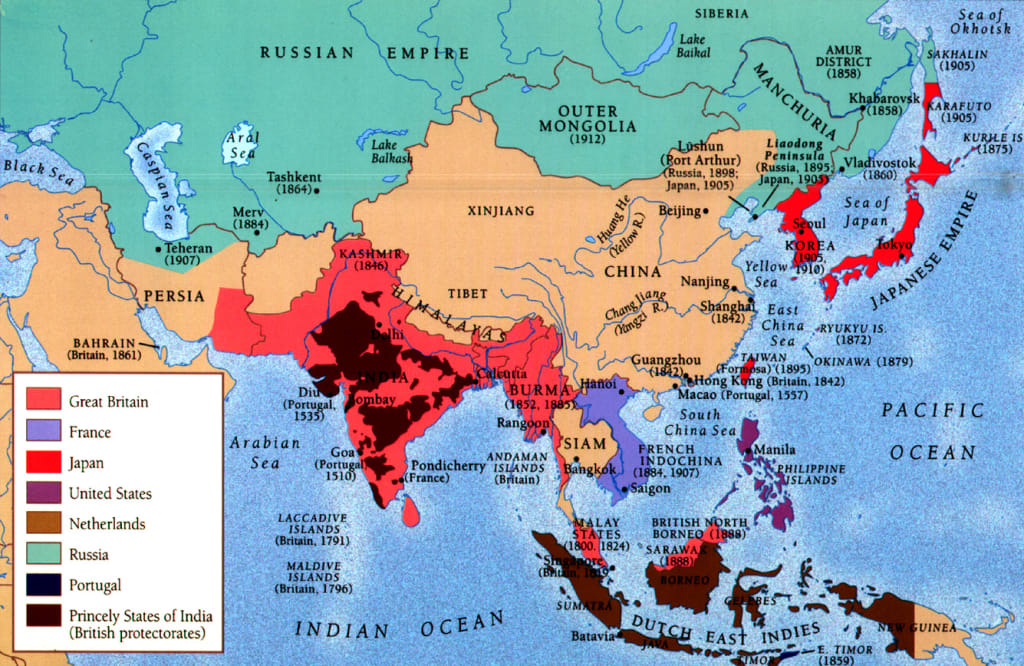

Several colonial powers, especially different Western Europeans, established colonies in Asia during the 18th and 19th centuries. Although they were on the same land, each imperial power had its style, from administration to colonial officials. As a result, the following countries showed different attitudes towards the people in their colonies. How do these colonial powers compare?

The British Empire was the largest colonial empire in the world before World War II, and encompassed some territories in Asia. These territories included what is now Oman, Yemen, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Iraq, Jordan, Palestine, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, the Maldives, Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei, Sarawak, North Borneo (now Indonesia), Papua New Guinea, and Hong Kong. The crown jewel of all of Britain’s overseas possessions around the world was, of course, India.

British colonial officers and British colonialists, in general, saw themselves as the epitome of “fair play,” and in theory, at least, all subjects of the crown were supposed to be equal before the law, regardless of their race, religion, or ethnicity. Nevertheless, British colonials segregated themselves from the local population more than any other European, employing locals as domestic servants but rarely intermarrying with the natives. In part, this may have been due to the transfer of British ideas about class division to their overseas colonies.

It is well known that the British colonial government took a paternalistic view of its colonial subjects, feeling a duty or a kind of white man's burden, as Rudyard Kipling put it, to Christianize and civilize the peoples of Asia, Africa, and the New World. In the Asian context itself, the British built roads, railways, and models of government, and acquired a national obsession with tea.

However, the British colonial structure quickly collapsed when the conquered people rose up. The British brutally crushed the Indian Revolt of 1857 and brutally tortured the Mau-Mau Rebellion fighters of 1952-1960. When famine struck Bengal in 1943, Winston Churchill's government not only failed to feed the Bengalis but also refused aid from the United States and Canada that was intended for India.

Although France sought a vast colonial empire in Asia, its defeat in the Napoleonic Wars left it with only a handful of territories on the yellow continent. These included the 20th-century mandates of Lebanon and Syria, and more specifically the major colony of French Indochina, now Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. As is well known, France’s attitude to colonial subjects was, in some respects, very different from that of its British rival. The idealistic French sought not only to dominate their colonial possessions but also to create a “Great France,” in which all French citizens around the world would be truly equal.

For example, the colony of Algeria in North Africa became a department or province of France, complete with parliamentary representation. This difference in attitude was perhaps due to France’s embrace of Enlightenment thought, and the long history of the French Revolution, which had broken down some of the class barriers that still governed society in Britain. However, the French colonizers also felt the “white man’s burden,” bringing so-called civilization and Christianity to people they considered uncivilized.

On an individual level, French colonials differed from the British in that they married local women, creating a cultural fusion within their colonial society. Some French racial theorists, such as Gustave Le Bon and Arthur Gobineau, however, criticized this tendency as a corruption of the French’s innate genetic superiority. Over time, social pressures mounted for French colonials to maintain French racial purity. In French Indochina, for example, unlike Algeria, the colonial authorities did not establish large settlements. Instead, French Indochina persisted as an economic colony, intended to generate profits for the home country.

Despite the lack of settlers to protect, however, as noted in “First Indochina War: Battle of Dien Bien Phu”, France quickly plunged into a bloody war with Vietnam when the Vietnamese under Ho Chi Minh resisted the return of the French after World War II. Today, small Catholic communities, a love of baguettes and croissants, and some beautiful colonial architecture are all that remain of the French influence seen in Southeast Asia.

Kallie Szczepanski in “Indian Ocean Trade Routes” explains, that the Dutch Kingdom competed and fought to control the Indian Ocean trade, and spice production with England, through their respective trading companies, in this case, the VOC and the East India Companies. In the end, the Dutch lost Sri Lanka to the British, and in 1662, lost Taiwan to China. Even so, the Dutch colonial government maintained control over most of the rich spice islands, which are now Indonesia.

For the Dutch, this colonial company existed for economic motives. There was little pretence of cultural improvement or Christianization of the people in the colony, but the Dutch wanted profit. As a result, they did not hesitate to cruelly capture the local population, and use them as slave labor on plantations, or even massacre the entire population of the Banda Islands to protect their monopoly on the nutmeg and clove trade.

After Vasco da Gama rounded the southern tip of Africa in 1497, Portugal became the first European power to gain maritime access to Asia. Although Portugal quickly explored and claimed parts of coastal India, Indonesia, Southeast Asia, and China, its power waned in the 17th and 18th centuries, and the British, Dutch, and French were able to push Portugal out of most of its Asian claims. By the 20th century, the only remaining territories were Goa, on the southwest coast of India, then East Timor, and the southern Chinese port of Macau.

While Portugal was not the most fearsome European imperial power, it did have the most enduring influence. Goa remained Portuguese until India forcibly annexed it in 1961, Macau was Portuguese until 1999, when the Europeans finally handed it back to China, and East Timor, now Timor Leste, officially became independent in 2002.

Portuguese rule in Asia in the context of its implementation, was also no less cruel and ruthless, such as when they began capturing Chinese children to be sold as slaves in Portugal. Like France, Portuguese colonialism did not oppose mixing with local communities and created a creole population. Perhaps the most important characteristic of the Portuguese Empire's attitude, however, was Portugal's stubbornness and refusal to back down, even after the central government declared its withdrawal or resignation.

Don't forget that Portuguese colonization was also inseparable from the drive to spread Catholicism, and at the same time make money. This was certainly inspired by nationalism that came from their history, the desire to prove the country's strength to get out of the power of the Moors, or the Muslim Andalusian nation, and in the centuries that followed, the urge to proudly hold the colony as a symbol of the glory of the past empire.

About the Creator

Wahyu Gandi G.

Researcher, writer, and lecturer | Obtained M.A. in Literature Science Universitas Gadjah Mada.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.