The Iranian Revolution, when communists and Islamists came together

For years, the Shah's regime believed that the only political opponents were the communists. But unexpectedly, an equally large resistance came from a group that had escaped the Shah's attention, the ulamas.

We often hear the narrative that religionists and communists are difficult and will never unite. The reason is religious groups think that communists are a group of godless people, while communists think that religion is opium. But who would have thought, these two ideologies that are placed at odds with each other could in fact unite, in a process of social change called revolution. The revolution in question is the Iranian revolution.

There is a popular saying that describes how drastically the country has changed, from Iran under the pro-Western Pahlavi Regime to later under the banner of the counter-Islamic Republic of Iran. "Before the revolution, people drank in public and prayed in their rooms. After the revolution, people prayed in public and drank in their rooms". That narrative perfectly captures the transformation of Iran from a secular, westernised country to one where people are expected to be religious.

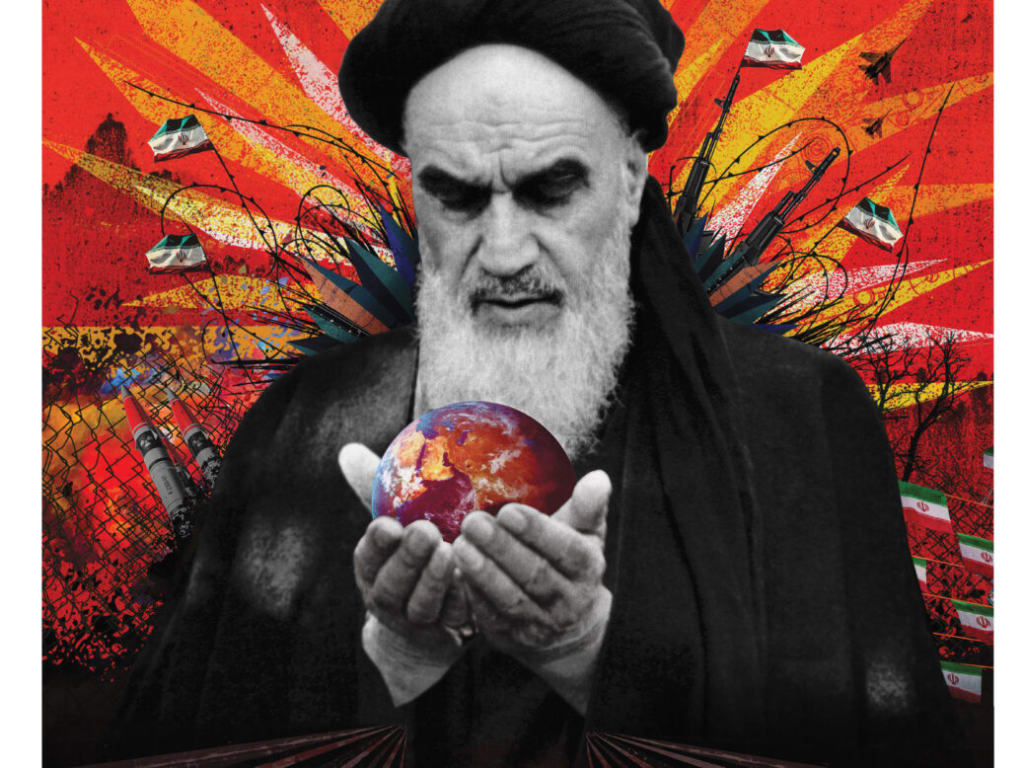

For those who don't know, the Iranian Revolution is generally associated with a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi Dynasty under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, and the replacement of its monarchical government with an Islamic republic under the leadership of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, more popularly known as Imam Khomeini. It is known, as explained that the revolution, which lasted from 7 January 1978 to 11 February 1979, was supported by various left-wing and Islamist organisations or progressive clerics.

In 1925, Iran under the authority of its National Assembly appointed a king named Reza Shah Pahlavi, after overthrowing the last ruler of the Qajar Dynasty, Ahmad Shah Qajar, and establishing a constitutional monarchy from the previous absolute one. This period began the Pahlavi dynasty's rule in the land of the mullahs. Under his leadership, Iran experienced rapid progress thanks to social, economic and political reforms. One of the policies taken was to send Iran's best sons and daughters to receive education in Europe, including his son Shah Mohamad Reza Pahlavi.

However, the rapid development of infrastructure, government institutions, and especially the economy and culture of Iranian society, on the other hand, has led to public discontent. Sandra Mackey in The Iranians: Persia, Islam, and the Soul of a Nation (1996) argues, that the most controversial is the replacement of Islamic law with Western law, the banning of traditional Islamic clothing, the separation of the sexes, and the veiling of women's faces with the niqab. Reportedly, the police even forcibly removed and tore off the veils of women who resisted the ban in public.

King Reza Shah Pahlavi governed until 1941, and his status as king was replaced by his son Shah Mohamad Reza Pahlavi. It is known that Reza Pahlavi strengthened his relationship with the West, and even did not hesitate to make the West his orientation. During his time in power, Shah Pahlevi sent thousands of people to jail who were considered dissidents, especially leftists. The looting of the communists stemmed from the policy of Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh, who wanted to nationalise a foreign company, British Petroleum. This policy was supported by Iran's communist party, Tudeh and the lower classes.

On the other hand, Reza Pahlavi felt that Mossadegh's growing political power could at any time undermine his authority. Therefore, in 1953, Mossadegh was coup d'état through Operation Ajax, which was supported by the CIA and M16. After the Prime Minister was eliminated, the Tudeh communists were dissolved. Its activists were arrested, jailed and killed. Shan Iran itself is known to have ambitions to become an influential leader in the world, while the US and UK view Iran as nothing more than a satellite state, or an important geopolitical proxy in the Middle East. The mutualism that has developed since the overthrow of Mossadegh has dragged the direction of Iran's foreign policy towards the West.

In 1960, the Shah launched the White Revolution, a massive modernisation project. These included the nationalisation of water resources, free education, the eradication of corruption and illiteracy, the right to vote for women, and more. However, these programmes did not benefit the common man. Between 1963 and 1976, Iran's economy grew by 8 per cent per year, with a third of its national income coming from oil sales. Per capita income rose dramatically, but unfortunately, the Shah only pursued growth statistics and neglected income equality. The impact was felt when inflation skyrocketed, especially when world oil plummeted in 1976. These conditions clearly fuelled public protests in Iran, and in turn, nurtured the seeds of a later revolution.

For years, the Shah believed that the only political opponents were the communists. Therefore, this group was the target of SAVAK, Iran's notorious secret police. But unexpectedly, an equally large resistance came from a group that had escaped the Shah's attention, the clerics. The agrarian reform policy threatened land ownership, which had supported religious activities. This was then exacerbated by the Secular Law that allowed non-Muslims to hold political office. Most of these clerics took to the streets. In June 1963, in the holy city of Qum, Khomeini made a speech denouncing Iran's leaders as "wretched and pathetic human beings". This led to his arrest, but soon triggered a wave of protests, including in the capital Tehran. The incident catapulted Khomeini's name among the anti-Shah community.

Khomeini also took on a very strategic partner, Ayatollah Taleqani, a left-wing cleric who had a wide network of underground communist guerrilla groups. At its peak in 1977, when the oil boom reached its peak, inflation soared, factories went out of business, and unemployment rose, all of Khomeini's agitation spread through underground newspapers and tapes began to be accepted as truth by the masses. The word revolution suddenly became associated with religion.

In the same year, the funeral of Mostafa Khomeini, the Ayatollah's son, in Muharram became a moment of consolidation for the Islamist opposition. They declared Khomeini an Imam and accused SAVAK of being behind Mostafa's death. The masses were fired up with agitative messages about the memory of Imam Hussein's death in Karbala. When the government was embroiled in a political crisis, Mostafa's funeral was an event that conveyed a serious message: fighting the Shah was jihad!

Since then, protests and strikes have become a daily sight in Tehran. Whatever was wrong in the daily lives of the citizens of Tehran began to be addressed to the Shah. On 8 September 1978, the Shah declared martial law. The armed forces, which had just increased personnel, were not well-trained to deal with the masses. The press reported 2,000-4,000 demonstrators shot dead. It was not until 1981 that Khomeini was elected President of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

About the Creator

Wahyu Gandi G.

Researcher, writer, and lecturer | Obtained M.A. in Literature Science Universitas Gadjah Mada.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.